Behind the Scenes of a Secret Interrogation Camp

Related Episode

I stumbled on the story of PO Box 1142 (Ep. #595) by way of my dad. One day he casually mentioned that Nazi POWs helped pick potatoes on his farm in Idaho when he was a kid. I thought, sure, Dad. But then I Googled it. Realized he was right. And spent the next few years obsessively researching America’s WWII POW program, poring through hundreds of documents and conducting dozens of interviews.

Related Episodes

Fort Hunt Park in Virginia

Credit: National Park Service

PO Box 1142—a code name—was one of nearly 1,200 camps on American soil during WWII. About 425,000 POWs were held in the U.S. during the war. Some in big camps, some in small, makeshift ones, like high school gyms and churches. A lot of the prisoners did indeed work on American farms and in factories. With so many men fighting overseas, there was a labor shortage.

Only two of the POW camps were used for interrogation, including PO Box 1142.

The site where PO Box 1142 was now looks like a pretty typical neighborhood park. It's now Fort Hunt Park, part of the National Park Service.

But during WWII, there were barracks, a guard tower, a fence – and a secret bunker dug into the ground and covered by trees. The government sent about 3,500 POWs here for interrogation. Some were transported on this bus, with blacked out windows.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

A bug found in PO Box 1142.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

The men who worked at PO Box 1142 interrogated German POWs, trying to gather intelligence that might help win the war. Many who worked at the camp were Jewish refugees from Europe who’d just fled the Nazis.

The men also listened to private POW conversations from the underground bunker. Every square inch of PO Box 1142 was bugged: the bedrooms, mess hall, even the trees. The bugs were the size of small watermelons.

Inevitably, some POWs found the bugs, and turned their rooms into studios – staging fake plays, mocking their interrogators, farting. Eventually the engineers learned to hide the bugs better, and the POWs mostly talked without suspecting a thing.

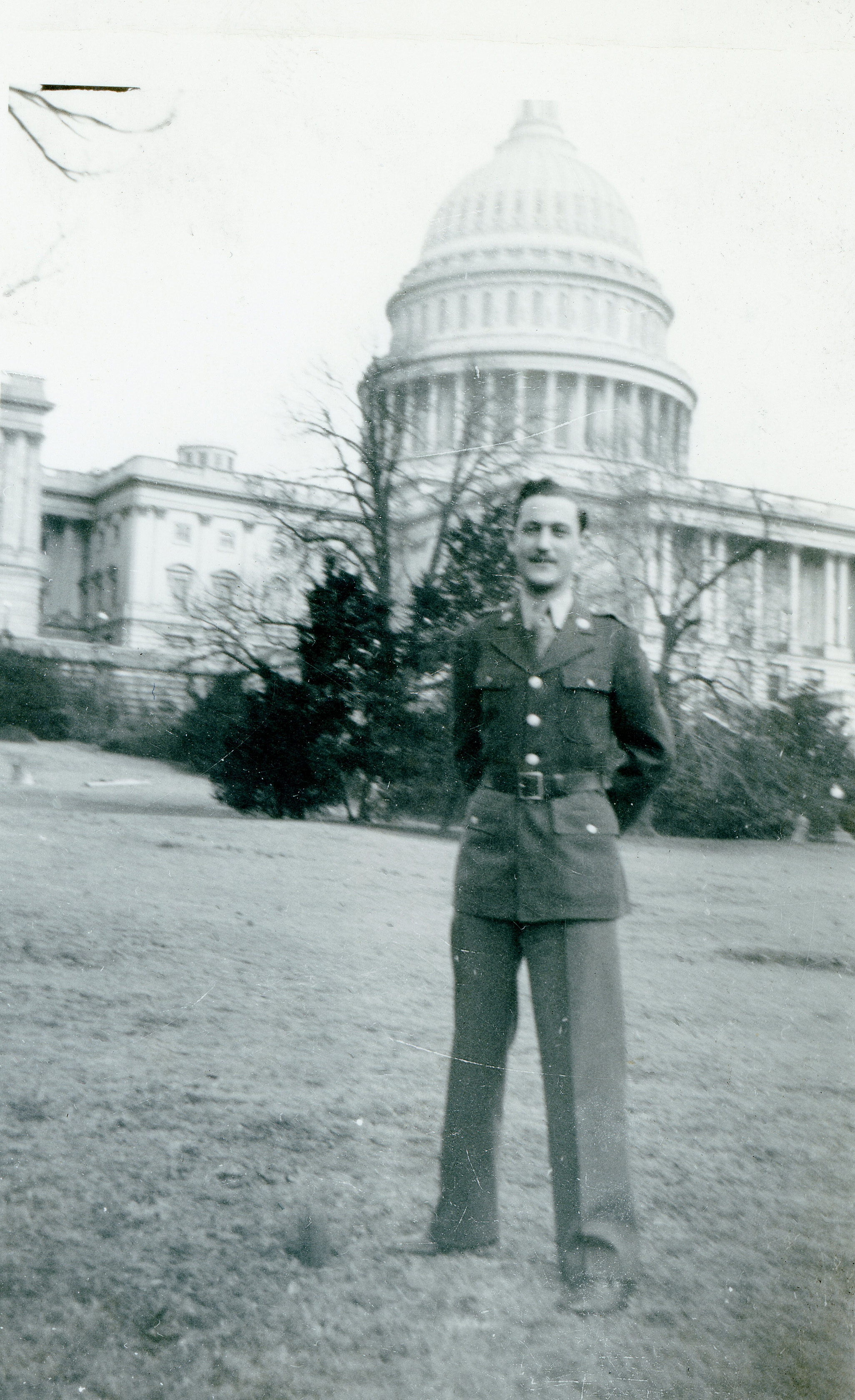

Werner Moritz

Credit: Courtesy of the Moritz Family

It sounds quaint now, but before WWII, the War Department considered surveillance “repulsive to … standards of civilized conduct.” When WWII came along, the military essentially said, You know what’s more repulsive than surveillance? Nazis. Men like Werner Moritz in our story did the tedious work of listening to POWs talk for hours on end. Monitoring these conversations yielded a huge amount of important intelligence.

Interrogation was another story. It was much harder to get POWs to talk in the interrogation room. Especially because this was America’s first time doing interrogation at this kind of systematic, strategic level; we were still learning.

Here are some of the tips they got from their interrogation instructor.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

And an interrogation training film, which includes mock interrogations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_SjWqF1Xc0

After interrogations, the intelligence men wrote up reports. Hundreds of thousands of pages of reports. This one was written by Moritz.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

The work here was top-secret. Most of the men who worked at the camp never spoke of it until the National Park Service contacted them over 60 years later. This is a copy of the secrecy agreement the men signed; you’ll see Moritz’s signature on page two.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

The men were finally honored for their work and spoke publicly about it for the first time at an event held by the National Park Service in 2007.

Last but not least, my favorite document: a press release about something called the “POW Coddling Report.”

Credit: U.S. National Archives

The opening paragraph says: “The House Military Affairs Committee has sent investigators into 25 prisoner of war camps … in the United States but found no evidence of prisoner coddling.” During WWII, some Americans felt the government was treating the prisoners too nicely, above and beyond what the Geneva Convention requires. So Congress investigated and released a “POW Coddling Report.” The investigation “found no evidence to substantiate the numerous rumors of soft and favorable treatment” of POWs.