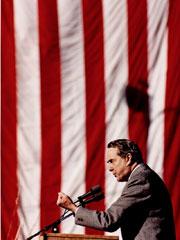

29: Bob Dole

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass.

Marilyn Monroe

Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday,

Woman

Mr. Presumptive Republican Nominee,

Marilyn Monroe

Happy birthday to you.

Marilyn Monroe

Everybody, happy birthday.

Ira Glass

See, this is the kind of event the Bob Dole campaign should have staged when he turned 73 this past week. They should have surrounded him with lively, young people, a big, happy event celebrating his vigor. A few of you may not know that particular piece of tape. It's a pretty famous piece of tape. It's Marilyn Monroe singing to John Kennedy in 1963, which in my view, makes it even more appropriate for Bob Dole to use.

Marilyn Monroe and John Kennedy are his contemporaries, after all. Bob Dole is 73. If Marilyn Monroe were alive, she would be 70. John Kennedy would be 79.

But instead of a big, lively event, a hall full of boisterous young people, where did the Dole for President campaign stage its big birthday photo op? In an old age home. There in the paper, you could see the pictures, Bob Dole with some senior citizens.

You really had to wonder, what were they thinking? What message are they trying to get across to us? Does this campaign have the will to live?

Well, each week here on This American Life, we choose a theme, invite a wide variety of writers and performers to take a whack at that theme with documentaries, radio monologues, reportage, found tape, occasional radio dramas, basically, anything they can think of. And today, we bring you perspectives on Bob Dole. Because at this point, there's something oddly mesmerizing about what's going on in that campaign. Barely a day goes by without some odd quote or strange gaffe.

Just at the end of this past week, there was a thing in the news how the Republicans have booked themself into a convention hall for the Republican Convention. And it's like 14 feet tall. And TV Guide was quoted in there saying that he doesn't want to make them look bad or anything, but there is literally no way to film them, to shoot them for TV, which is the entire point of a modern political convention. There's no way to shoot them without them looking like ants on a postage stamp.

And I see this stuff. And really, my heart just goes out to the man. Something deep and codependent in me wants to step in and help him out.

Anyway, our program today in three acts. Act One, Campaign Diaries.

Act Two, Instructions on How You Can Become Bob Dole.

Act Three, a writer who we've been trying to get on our program for a while, actually, a guy named Danny Drennan. Usually, he writes about things like the TV show Beverly Hills, 90210. And we gave him a little assignment. Anyway, stay with us.

Act One: Campaign Diaries

Ira Glass

Act One, Campaign Diaries. Well, before on this program, once before, we've featured the campaign diaries of Michael Lewis. And he is covering the political campaigns. He's one of the people writing for The New Republic.

And his writing is really some of the most remarkable writing anybody is doing about the campaigns, because basically, he's this really funny, smart guy who writes like a novelist, more than like a political reporter, though there's a lot of political analysis in it. The political analysis gets encased in these scenes, in these little stories. And it's just a complete pleasure to read. And then he's just got a really great eye, a really great eye for the telling moment. And he's been following around all the different candidates.

We're going to play you now a set of stuff that he's written about Dole, just because, among other things, he captures all these moments nobody else gets. And they reveal all these things about Dole and his campaign. I'm going to start with this. Let me get some music going here again.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

There we go. This first little diary entry is from back during the primaries. This is February 15. This is after the final New Hampshire debate. And this is this debate where there was this one moment where Dole kind of got into a little shouting match with Steve Forbes. Remember him?

And Dole basically said to Forbes-- Forbes was running all these negative ads. And Dole's staff or Dole came up with this stunt where Dole would say "Those ads are really inaccurate. And plus, if you're going to be talking about me, you could at least use a decent picture." And then Dole hands him these pictures, which Forbes snaps back at him, this and that.

OK. So all that gets covered in the press. But after the debate, people leave. The stage is empty. And our little Michael Lewis heads out onto the stage. And he's looking at all the detritus left over, the notes the candidates write themselves, all this stuff that nobody else really bothers with writing about.

And then he sees the photographs. I'm going to read from this campaign diary, and then we'll go to Michael reading. He says, "I noticed the photographs. They lay on the shelf beneath Forbes's podium. They were not prints but originals, curled and soiled, as if they'd been sitting in some shoebox for years, until Dole stumbled across them late one night while he was worrying about how to retaliate against Steve Forbes in the big debate.

Two are color, a bad one of Liddy, Dole's wife, who's stunning in the flesh, looking here tired and plain. A better one of dole's dog, Leader, rubbing noses with a yellow lab. The third is a black and white, of Dole smiling broadly, holding a baby. He looks 20 years younger. The black pen he clutches to keep his right arm in place juts up and is set off by the baby's white gown. Dole is looking at the camera. The baby is looking at Dole's gnarled, wounded hand." Here's Michael Lewis.

Michael Lewis

I asked five different Dole aides the identity of the baby held by Dole in the photograph he gave to Forbes. It seems an innocent enough query. After all, this was the picture Dole had selected for publication. I get no answer.

The basic pose of the Dole campaign is the less anyone finds out about their candidate, the better. You can spot the Dole office in the row of glass boxes on the ground floor of the New Hampshire Holiday Inn. It's the one with the newspaper taped up on the glass to prevent people from outside looking in. Dole himself remains largely out of sight. He makes two or three very brief appearances each day and is otherwise unavailable for interviews.

Dole's speeches add nothing to the general blank picture. A dozen times I listened to his talk, pen poised idly over paper. Nothing, not a thought, not an image, not a quote.

It took me a while to figure out why this was, but then it struck me. Bob Dole wasn't running for president. The concept of Bob Dole was running. The man himself had subcontracted out all the dirty work to people who make their careers out of this sort of thing. That was why he was referring to himself in the third person. He wasn't there, at least not in any meaningful way.

It turns out that everything I will discover about Bob Dole, I will discover by stealth. My first discovery? He's embarrassed by his own vanity. I catch him in a back room at one event, just before he's about to go onstage. He thinks no one is looking. He checks out his reflection furtively. His hair is sprayed and dyed. And then he whips out of his pocket a tiny canister and squirts two quick blasts of breath spray into his mouth.

Also, his wit is genuine. It's not just an act. I stalk him through the snow at the world dog sledding championships and watch him meet and greet the pooches. A schoolgirl approaches as he's about to leave and after nabbing a photo, asks him if he's having fun. "You learn a lot out here campaigning," Dole says, motioning to a sled of 20 dogs. "They're all nice dogs, too, not like the Congress." He thinks no one is listening. He's said it just for the fun of it.

All other data about Bob Dole must be inferred from the world he has created around himself. The Dole campaign consists of slick young men in blue suits, forever whispering to each other in dark corners. The campaign pays top dollar for everything. And I get the feeling that most who work for it have some personal financial stake in Dole soldiering on, and that they'll be the last to tell him that he really shouldn't be doing this again.

You also get the feeling that there is very little the campaign would not do. One of their favorite techniques has been to hire telemarketing firms to call Buchanan supporters and, in the guise of pollsters, relate damning untruths. In response to Buchanan's complaints, the Dole people tell reporters that Buchanan is doing the calling to a few of his supporters to tar Dole. It takes a special sort of credulity to believe them. I stopped half a dozen people carrying Buchanan signs who told the same stories of strange phone calls in the night.

One afternoon, I abandoned the Dole campaign for the steam room at the Manchester YMCA to purge myself of the dreadful feeling coming over me. A few minutes later, an extremely fat old man waddles in, spies me, drops his towel, and sits on a plastic stool right next to me. "You're a new face," he says. "I always notice a new face." I say, "That's nice," grab for a towel, and tell him I came for the campaign.

He shifts on his stool and says, "I'm a Buchanan man, myself." Buchanan men are the kind of guys who can sidle up to other guys in steam rooms without the slightest fear of being thought gay. Moments later, he's complaining about the calls he's getting at home. Here, roughly, is what he said.

"A guy calls. He says, 'Hi. My name is William, and I'm calling from the Dole campaign. Are you aware that Pat Buchanan is an extremist?' And I say, 'What do you mean?' And he says, 'Pat wants to give nuclear weapons to South Korea and Japan.'

So I ask him, 'Where does this information come from.' He says he doesn't know. So I ask him, 'What does Bob Dole think about that?' And this kid doesn't know that, either. He knows absolutely nothing about Bob Dole.

So I ask, 'Who are you, anyway?' And he says he's with an organization called the National Research Institute in Houston. So I ask him for his phone number. And he says he can't give it to me. Then he hangs up. There is, of course, no listing in Houston for the National Research Institute."

In short, the Dole campaign is a lot like what a lot of people probably suspect the Buchanan campaign is, closed, secretive, smug, a bit nasty. Maybe that's what happens when you lose once too often. You stop trusting the voters.

And yet I still want badly to like Dole. I'll bet he's the guy in the race that people most badly want to like, but can't quite figure out how to do it. Every night after a day with Dole, I return home and recall to my mind a pair of mental images that the day has badly blemished. The first is the one of Dole recuperating from his war wounds, as described by Richard Ben Cramer, hanging by his bad right arm and trying to straighten it out until he was sweating and crying from pain. The second is a windy afternoon last June in a graveyard on the French coast, when, Dole now says, he realized he had to run for president one last time.

I traveled there on Clinton's plane to witness the D-Day celebrations. But about halfway through, I lost interest in writing about it and just started watching. You gaze down the cliff onto the beach and just marvel. How did these men do this?

Just before Clinton addressed the veterans of the Normandy invasion, I found myself walking alone through the rows of white crosses, until I reached a place where there was no one else but a pair of veterans. They seemed ancient, though of course, they could not have been much older than Bob Dole. They were trembling and leaning on each other as they looked down on a cross. And at first, I thought it was just from the strains of age.

Then I saw the name and place on the cross, Stenson, I'll say, from Mississippi. The boy had died at the age of 19 on the first day of the invasion. The old men wore name tags, too. Stenson, from Mississippi.

Two of three brothers had survived that day. They were crying without tears. That's a bit like Dole, I would like to believe. He's crying without tears. He has the emotions, or at least, you can sense them lurking inside them. But he has no idea how to give them proper expression.

Ira Glass

Michael Lewis. We'll continue with his campaign diaries in a bit. It's This American Life.

[MUSIC PLAYING - "THE DUTCH BOY" BY THE HANDSOME FAMILY]

That's The Handsome Family, a Chicago band. We'll have more campaign diaries from Michael Lewis in a second. First, I wanted to read a little bit from this piece written by Andrew Sullivan, also in The New Republic. Figured we're doing one, might as well do the other. It's this lovely little piece of writing from a couple weeks ago.

He begins this thing by talking about this sketch that apparently, they're doing on Saturday Night Live. It's a spoof of MTV's show, The Real World. And in the real show, The Real World it's a bunch of young people in their 20s, Generation X-ers, living in a home somewhere. And they locate the home in different places.

In the spoof, it's the same setup, except apparently, Bob Dole is living there with them. And then that's the big joke, that this gruff, 70-something person is living with the 20-somethings. And Andrew Sullivan makes the case, no, no, there's actually something to be learned from this. There's actually a deeper truth that we can find in this. He writes the following.

"Bob Dole, very unlike his rival for the presidency, is actually, I think, a natural Gen X-er, someone whose ironic detachment, bleak humor, and occasional bursts of dark sentiment make him far more intelligible to the under-35 crowd than most politicians. At 72, he is in some ways the ultimate 20-something candidate. To wit, his remarkable, revealing, and insistent use of that quintessential Generation X mantra, 'whatever.'"

And then he's got a whole bunch of examples of Bob Dole using the word whatever, whoever, wherever, the various permutations. Here are some. Let's see.

"Well, I think Lowell Weicker probably did more in the Congress of the United States for disabled people in this country, children, adults, whatever." Or, "That's one way to address it for some people. But you're right, all economic classes, whether you're white, black, whatever."

The hint here, Andrew Sullivan writes, is that Bob Dole knows he's reciting a list of groups that he should feel deeply sincere about. But he can't at that moment feel completely sincere about them. So he gently undercuts the blather he's required to express by adding the W word.

We know he's in favor of helping the poor, underprivileged, disabled, veterans, whomever. But we also know he's not exactly smitten with empathy for their plight as he utters the words. He cares, but with an understandable and often funny level of detachment.

Compare with Clinton. A "whatever" barely passes the president's lips. There is nary a scintilla of detachment from his sympathy for everyone and anyone at all times, and indeed a fear, even panic, that anyone might suspect otherwise. Dole is different.

Sullivan goes on in a little section of this to argue that this ironic distance is actually something admirable, in a certain way. He quotes a couple more examples of him saying "whatever" in different situations. He says, "There are signs that Dole is aware of the complete silliness of much of what passes for political ritual. He knows that the throngs cheering for him today will be cheering for someone else tomorrow, that enthusiasm is fickle, that real support for someone like him always has something completely contingent about it. So he condescends to it under his breath in a throwaway, that wistful grin snickering up his face toward his black, darting eyes.

Like the members of Generation X, Dole is post-just-about-everything. The difference, of course, is that he lived through it, and they were born after it. Dole, it's clear, has few illusions about the world. He's seen white-shirted revolutionaries have their moment and leave nothing but a deficit behind. His irony is not, as some boomers would have it, an expression of ennui or listlessness or cynicism. It's the sanest response to the real world, if you'll pardon the expression.

Members of Generation X, despite the fashionable assumption, are not disillusioned. They're merely un-illusioned. Their wariness is endemic. Dole gets this. Clinton never will."

Anyway, that's by Andrew Sullivan. Let's go to more of my Michael Lewis's campaign diaries.

Michael Lewis

February 19. The act, I should say, is always the same. The announcer brings on stage, one at a time, all the politicians who have endorsed Dole. They race out onto the stage like ballplayers before a game. Dole waits in the background until the crowd reaches a low fever pitch. A quick squirt of the breath spray, and he's on.

He stands at the podium with his left foot and left side jutted forward, though he's right-handed. His crippled right hand rests on the podium, but it's not a prop. He'll start in with something self-deprecating. "That's a lot better than the speech is going to be." Something like that.

Presently, the voice of Dole emanates from the Milford, New Hampshire, town hall's facade. It's not so much a speech as a series of disconnected phrases uttered in an elegiac tone, some of which cause the people around me to break out into giggles. "Like everyone else in this room, I was born," Dole says. A Dole speech sounds like the sort of thing a red brick building would say if a red brick building could speak.

He pulls the rhythms of his "one America" refrain up short, just as it starts to flow. "We're not rich. We're not poor. We're not urban. We're not rural. We're not black. We're not white. You can go on and on and on." I have a dream, kind of. And gentleman in England now abed, well, I don't know. Maybe they should just get up.

It is more like the Cliff Notes of a great speech than the speech itself. The only lines Dole can deliver with any kind of strength sound like they were cribbed from Robert's Rules of Order. "Start the hearings. Go through the process. Do it in an orderly way."

The whole time Dole is speaking, it is as if he is saying, "This is the speech I would give to you if I was the sort of person who gives speeches." I'm not sure whether Dole is actually modest or simply embarrassed by immodesty. I leave thinking that a man like this runs for the presidency not because he thinks he should be president. He thinks no one else should be president, so it might as well be him.

May 27. You never saw a more unhappy-looking group than the journalists assigned to follow Dole into New Jersey on Memorial Day. "I got the best seat in the house to the worst show in town," rumbles a cameraman as we board the plane at National Airport. "I just came in case he got shot or something," says a reporter, who doesn't even bother to take notes.

I, too, have my misgivings. Usually, my campaign notebooks are crammed with anecdotes, observations, and incidents. Whenever I'm with Dole, however, they simply refuse to fill up. The Dole campaign remains an arid, sterile place. Not much grows there.

Today is a kind of prelude to the general campaign, which will be relaunched in earnest tomorrow with a bold journey across the country. Dole marches for a dozen blocks through Clifton, New Jersey, in front of the parade's single float, bookended by his wife, Elizabeth, and Governor Christie Todd Whitman. The crowd is quiet and sparse, less than one deep.

The parade climaxes in a park, where Dole is meant to make a few remarks and lay a wreath on a symbolic grave site. I wait there for him, watching members of the local veterans organization subtly jockey for position. Six old men form the color guard, dressed in red jackets, VFW caps covered with patches and buttons, and the apprehensive air of people who fear they might be asked to improvise.

But the really striking thing about them is how old they look, at least compared to Dole. They could almost be a different generation. "Any veterans of the first World War here?" I ask. "We just buried our last one last fall," says one, who sports a POW-MIA pin in his cap. "Don't come around here 10 years from now," says the man beside him, "or we won't be here, either."

May 28. It turns out that we are flying all the way across the country to spend less than 24 hours in California before picking up and flying back. First to Chicago, where we'll spend tomorrow night, and then to Ohio, on May the 28th, five months before the election. The only reason it doesn't seem insane is that several hundred seemingly sober men in dark suits follow Dole wherever he goes. There is a kind of ambitious young person who mistakes frenetic movement for advancement in the world. They'll call you from the road and say, "I'm in Bangladesh on business, heading for Iceland." And you know that he thinks this is sufficient explanation of his purpose in life.

The Dole campaign has something of this feeling. As long as the candidate keeps moving, everyone traveling with him is exempt from serious self-examination. Which is a shame, since they have no idea why they are doing what they are doing. It's frequent flyer politics.

And within a couple of hours, I'm having my first Admiral Stockdale moment. Who am I? What am I doing here?

Early the second morning, we descend, in our motorcade of 13 cars and 2 buses, on a seemingly tranquil park in Redondo Beach. The point of the event and the trip is to illustrate that Dole is against crime. The trouble is that Clinton is against crime, too. So Dole needs to show that he's more fervently against crime than Clinton, who at this very moment is on route to New Orleans to deliver his own anti-crime speech. Dole and Clinton are like Time and Newsweek. No matter how much they claim to differ, they still run the same covers, week after week.

The park is being celebrated as an example of a neighborhood reclaiming public space from urban violence. But as various political dignitaries loudly disapprove of drive-by shootings, a small group of dissenters forms on the fringe. All but one are the Hispanics who bear the brunt of the new anti-crime esprit. They're hauled off to jail for all sorts of odd crimes, carrying baseball bats into the park after 7 o'clock in the evening, for instance.

The exception is a gentle old soul named Art Campbell, who for decades has cleaned the park, coached the local kids, and groomed the playing fields. The ball field at the center of the park is named for him. Art Campbell is a Dole supporter. "I'm for the man," he says. "I don't go by the party." But he's mildly perplexed by the anti-crime rally. "It isn't as bad as all that," he says.

A policeman on the scene confirms that the crime statistics in Redondo Beach are in line with those of the nation as a whole. Violent crime has declined steadily here, as it has in other cities, over the past 20 years. More to the point, he cannot recall a single violent crime in the park. "A few years ago, someone shot a gun in the air as he drove past the park," he says, "But no one was hurt."

Campbell stops the park custodian, a Hispanic man who speaks poor English. "Do you think this Dole thing is a good idea?" he asks the man. The man takes one look at my notepad and says, "I no want to say." He's afraid of offending his employers. The greatest fear in the park is the fear of offending the people on the platform who are spearheading the anti-crime initiative.

Having successfully fed, and fed off of, the fear of crime, we wearily board the bus. I am now certain that nothing interesting will ever occur in the close-cropped frame of the staged Dole event. Where do politics come from, anyway? Not from listening to Bob Dole deliver a speech written by someone else to a group of people he knows nothing about in a place to which he'll never return.

Many of the criticisms about Dole can be made of Clinton, too, of course. You can't say anything about Dole's use of push polls, or about the cynicism of his staged events, without having some seasoned reporter look at you as if you were a child and say, "So what? They all do that."

The next week, the New York Times will carry a putatively positive piece about Dole's campaign manager, Scott Reed. Toward the end of it, almost by-the-by, we read this astonishing revelation about Dole's senate resignation. Quote, "The element of surprise was essential, Mr. Dole and Reed decided, if the announcement were to appear bold and make an impression on voters. 'If it had leaked,' Mr. Reed said, 'he probably wouldn't have done it.'"

Think of it. Just a few weeks ago, the man stood before us and brought tears to our eyes by saying that you do not lay claim to the office you hold. It lays claim to you. Your obligation is to bring to it the gifts you can, of labor and honesty, and then to part with grace.

But according to Reed, Dole's decision to end his wonderful senate career was baldly conceived as a PR stunt. Journalists are often accused of being cynical. But the cynicism of journalists does not compare to that of serious presidential candidates.

Ira Glass

Michael Lewis. His campaign diaries can be read in The New Republic. He's the author of Liar's Poker, which is a really funny, interesting, wonderful book that we strongly recommend. Coming up, how you, you, can imitate Dole for your friends and family, and Mr. Danny Drennan. That's all in a minute when our program continues.

Act Two: How You Can Be Bob Dole

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a subject and invite a variety of writers and performers to take a whack at that subject with a variety of different kinds of stories. Today, our topic is Bob Dole. We've arrived now at act two of our program. Act Two, How You Can Be Bob Dole.

For this act of our show, we welcome to our show a man named Robert Smigel. And Smigel impersonates Bob Dole on Late Night with Conan O'Brien. He used to impersonate him on the Dana Carvey Show, a short-lived program. Smigel himself is former head writer with Saturday Night Live. And he's probably best known for a sketch that he created.

To describe this thing, it's one of these things, it's almost hard to believe that a single person came up with this idea. Because it's just one of those things that just seem to spring out of the collective unconscious of our nation. This is a sketch that on Saturday Night Live, they called the Superfans. It was a bunch of Chicago, Chi-caw-go, guys, big guys, who would talk about Da Bears, Da Bulls.

Robert Smigel

My tombstone will say "Da Corpse," I think.

[LAUGHTER]

Ira Glass

Anyway, so at some point, it became clear that Smigel was going to be the person who was going to be imitating Bob Dole on the Conan O'Brien show. And by the way, when he does this, what appears on a screen, there's sort of a TV monitor comes down from the ceiling. And then Conan O'Brien talks to the monitor. And on the monitor, you'll see a photograph of Dole.

And then the lips are chroma keyed out or something, so you don't see those lips. What you see is Smigel's lips. And then he does Dole's voice.

So when it became clear that he was going to have to imitate Bob Dole, he set about to design. He had to think about it. He had to plan it.

Robert Smigel

Instantly, I thought of Dan Aykroyd's impression, which was ingrained in my head from working at Saturday Night Live. And what I try to do is find something and take it further, because otherwise, it's just boring to do what Dan Aykroyd did. And so I started with the monotone thing. It's sort of how you have to get into it is just, "Bob Dole. Bob Dole pronounces, emphasizes every word about the same way. It's kind of like a test pattern, [? Dooooole. ?] That kind of thing."

And Dan Aykroyd kind of does the bully Dole from the '70s. Dole back then was sort of a Nixon protege. And then I figured I'd take it a little further and make it a little munchkin-like.

"Because Bob Dole tends to, when he rolls, when he keeps going, [UNINTELLIGIBLE], you'll be hist-- you'll be hist-- you'll be history." That kind of thing. Then I figured out that Bob Dole is actually the tree from The Wizard of Oz. He's not a munchkin. He's actually--

Ira Glass

Wait, let's pause on the munchkin. What is the quality that makes it munchkin-like.

Robert Smigel

Mayor of Munchkinland, you know. "And she's not really, really dead. She's really most sincerely dead." Kind of sounds like Bob Dole. "Not really-diddily dead. She's really-- let me tell you something. Bill Clinton's campaign is dead."

But anyway, what he's really like is The Wizard of Oz tree, which is, "I'm Bob Dole. How'd you like it if somebody took apples off of you?"

[LAUGHTER]

Robert Smigel

You know, he's even got the same expression as the tree. And he's tragic in the way the tree is. People are constantly pulling apples off, and they're not tasting them. I've got about five minutes more on this analogy.

Ira Glass

Yeah, keep going.

Robert Smigel

Pshaw. Nonsense, Conan O'Brien. Now you listen to me. Bob Dole wasn't last night. Bob Dole's the new president of the United States, that's right.

Dole's on a roll. Dole topped the polls. That's right. Dole's in control. Dole's riding a bull-Dole-zer. Shoot that punk. Shoot that punk, smoke that Dole.

Ira Glass

There's actually something kind of sweet about your imitation of Dole on Conan, because he's always a little bit giddy.

Robert Smigel

On Conan? Yeah.

Ira Glass

He almost seems deliriously happy.

Robert Smigel

Oh, well, I'm just imagining his deepest thoughts. And he's just letting them out at 12:30 at night, when no one's watching. That's sort of the premise. Like, "Bob Dole's the next president of the United States. [UNINTELLIGIBLE]. Sing with me, O'Brien." And I would make him sing, you know, "Happy Happy Dole Dole."

--Dole de-Dole de-Dole.

Conan O'Brien

Wait a minute, Max, Max.

Robert Smigel

Dole de-Dole, Dole de-Dole. Dole-de--

Conan O'Brien

Those are the stupidest lyrics I've ever heard.

Robert Smigel

Dole.

Ira Glass

The thing about it that's so appealing is that it shows Dole taking pleasure in something in a way that we never get to see him do in real life.

Robert Smigel

When I do a politician on that show, I'm almost always doing the id of that politician. It's basically nonsense. And sometimes I just have Dole giggling, and just--

Ira Glass

"Bow to me" is one of my favorite things.

Robert Smigel

Bow down to me, Conan O'Brien. Bow down to the next senate majority leader, most powerful man in the world.

Ira Glass

Do you feel a certain affection and closeness for Dole? I would think actually imitating somebody, you would have to develop that.

Robert Smigel

Yeah, I really-- it's hard not to like Bob Dole anyway. I mostly feel sorry for him. To me, it just seems like it's only going to get worse for Bob Dole. At the point where he's supposed to catch up, where everybody expects that it's going to tighten, that's when they're going to debate. And Bob Dole needs to have a 20-point lead before they start debating.

Ira Glass

Do you do him sometimes around the house?

Robert Smigel

Unconsciously, yeah, sometimes. I just got a puppy, and I find it very effective training.

Ira Glass

Really, like how?

Robert Smigel

Very effective, just when I put on the Bob Dole voice at the puppy. "Sit! You listen to me, puppy. You poop."

Ira Glass

If you've seen Robert Smigel's imitations on the Dana Carvey Show, and actually, apparently, not many of you have, because that show did not last very long on the television, Smigel's imitation on that show was kind of cruel to Dole. He basically played Dole as this doddering old man who could barely string together two or three words in a sentence.

And in this imitation, in this version of his imitation, periodically, Dole would just lose it. He would just forget where he is and what was going on. In one sketch, Smigel actually has Bob Dole going around saying, "Why won't Bob Dole debate me?"

Robert Smigel

That's right. That's how I used the Bob Dole thing there. He's lost track of who Bob Dole is. "Why won't Bob Dole debate me? Bob Dole is hiding. Somebody--" And then he turned around and started yelling at the people behind him, like he thought they were the audience all the sudden.

Ira Glass

As somebody who has done an imitation of Dole where he's the boisterous, slightly bullying with Conan, the "bow to me" Dole, what do you make of this whole kinder, gentler, personable, "I'm going to tell you my real story," how do you think it's coming off? You think it's working?

Robert Smigel

Well, we've made fun of that on the Conan show, too, you know.

Ira Glass

Really?

Robert Smigel

Yeah. Well, we've segued from him going, "I tell you, Bill Clinton's going to jail. Hillary Clinton's going to jail. Socks the cat's going to jail. Oh, what am I talking about? What's happening to Dole?

Like that, O'Brien? That's a new Dole. New Dole cries. New Dole cries. Boo-hoo. Like it?" This man has cried more-- I don't think there's a politician who's cried in public more than Bob Dole. It's such an amazing flip side to the guy, who's looked down as such a hardass.

Ira Glass

Wait, when has he cried? Let's list the times. There's at Nixon's funeral, right?

Robert Smigel

Nixon's funeral. He cried in Russell, Kansas. He cried a little bit when he announced his resignation this year from the senate. And he cried when he went to Russell, Kansas. I mean, that's twice this spring. And then he cried at Nixon's funeral.

Ira Glass

And do you buy it?

Robert Smigel

Do I buy it? Yeah. Well, I buy the Nixon's funeral one. There didn't seem to be any political upside in that one.

Ira Glass

Yeah, that's true.

Robert Smigel

So if you buy that one, then you have to think that it's possible that he was sincere in the other two. I can imagine the senate one would be hard for him. The Russell, Kansas thing, that stretches credibility a little bit. Because basically, he only goes to Russell, Kansas to cry. Supposedly he's never there except to make a speech once every eight years, when he runs for president.

Ira Glass

It's actually an odd thing to have a place where you go to cry. You know what I mean? What if every time you wanted to cry, you had to hop the train to Newark?

[LAUGHTER]

Ira Glass

It could be a burden on a relationship, for one thing.

Robert Smigel

Got to go to Russell. Oh my god, I'm feeling a little bummed.

Ira Glass

So let me ask you, do you have any tips for our listeners who might want to be imitating either candidate during the coming months?

[LAUGHTER]

Ira Glass

Just a couple of pointers on how they might handle it. Give us a couple for Clinton and a couple for Dole.

Robert Smigel

You mean just physical moves?

Ira Glass

Yeah, physical moves, sure.

Robert Smigel

All right. Well, Bob Dole, I sort of walked you through Bob Dole. Start with the test pattern, "Nnnnn."

Ira Glass

The monotone.

Robert Smigel

"Dole, and everything is monotone after that. And he says the same thing in the same tone of voice, speaks very rapidly, Dole." And then putting an "Nn" before the Dole makes him seem older. "Nn-Dole," that kind of thing.

Ira Glass

Clinton, any tips for Clinton?

Robert Smigel

Well, it depends on how far you want to take one. If you want to do the crazy Clinton, then that's easy. You start with Bruce Springsteen.

And it's just, "Hey, little Mary with your daddy home. Hey, man. How you doing? How's it going, everybody? Whee-haw."

But then there's more of a-- the more accurate Clinton is kind of the caring guy who's just sort of a gentle thing. And it takes very little, very little energy. You just barely, barely breathe, hardly at all.

Ira Glass

You barely breathe. Also, your voice is going all the way to the back of your throat, isn't it?

Robert Smigel

When I'm doing this, yeah. I feel the air. That's very good, yes. I feel the air pushing toward the back of my throat.

Ira Glass

Robert Smigel, he imitates Bob Dole still on the program Late Night with Conan O'Brien.

Act Three: TV Politics

Ira Glass

Act Three, TV Politics. Most of us experience Bob Dole, the real Bob Dole, on television. Most of us actually experience most politics in this country through television. And we thought to discuss Bob Dole as a television figure, we would get somebody who writes about TV.

And the person we got is a guy named Danny Drennan. And he writes something on the World Wide Web called the "90210 Weekly Wrapup." And this is about the TV show Beverly Hills 90210.

The way he writes about television, he is in his own genre of writing. He careens from sheer cattiness to his own analysis of the program and how it's produced and all the actors, and then what all that means for the nation as a whole. Periodically, he'll digress into little personal stories about his own life.

And so we at this little radio show adore his writing. And in fact, if you want to visit his website, we recommend it. The address is www.inquisitor.com. He also publishes a zine called Inquisitor.

Anyway, so we invited him, and we were really glad when he said yes. We invited him to do something for our show. We asked him to watch Bob and Elizabeth Dole when they appeared on a recent hour of Larry King Live.

Danny Brennan

So I'm watching Larry King Live the other night, and Bob Dole is wearing a dark gray suit and a powerish, reddish tie. And Elizabeth Dole is wearing a blue, blue dress and Red Cross red lipstick, which I guess means she's going for that red, white, and blue effect. And the first question is about the statement made by somebody that Hillary should debate Elizabeth.

And Bob Dole is like, "It was a joke." And Elizabeth Dole is like, "It was in jest, Larry." And then Elizabeth Dole goes on and on about how the emphasis should be on the presidential candidates, which is funny, because she doesn't let poor Bob Dole get a word in edgewise.

So next, Larry King is asking whether there are any women on "the list" for vice president, since Elizabeth Dole said that in our lifetime, there would be women presidential candidates. And Bob Dole goes on and on about his process for picking a VP. And Larry King, sounding like someone out of The Godfather, is like, "But you know all of these guys. What do you need a process for?"

And Bob Dole starts to list the things he looks for in a vice president. And two of them are health and age, which I thought kind of weird. Like maybe Bob Dole shouldn't be allowed to say the words health and age at all. And all I could imagine was a room full of Dole campaign handlers in Larry King's green room going "Damn!" at the top of their lungs.

So then there's this whole thing about Katie Couric's interview of the Doles, and how she didn't stick to her script and just talk about the book that the Doles have written, which I guess was Elizabeth Dole's cue to start talking about the book, which she did. And she reads the inscription she wrote to Larry King, which goes "To Larry. Here's hoping that Larry King Live will be broadcast live from the Dole White House, 7-15-96. And your program is mentioned in the book, Larry."

I totally think that Elizabeth Dole is shaking down Larry King. Maybe he won't be interviewing the Gores or the Clintons because Elizabeth Dole gave him the plug in the book and that emphatic, sternly scolding "Larry" at the end. And then Larry King points his gatling gun mouth at Elizabeth, who, with a big old smile on her face, is like, "I thought we were there to talk about the book, Larry." Like, how harsh is Elizabeth Dole? I seriously would never want to be on Elizabeth Dole's bad side.

Next, they're going on and on about how badly the campaign is doing. And Elizabeth Dole is talking about how no one is engaged because it's summer vacation. And Larry King is all, "Well, you know the media. Today's mistake is tomorrow's headline." And how weird to hear Mr. Media Manipulation himself talk about the goings-on of the media as if they are a totally natural state of affairs that he himself has nothing to do with. How annoying is that?

And then Bob Dole, instead of casually dropping his buzzwords one by one into the conversation, just reels off a whole bunch of them wholesale. And meanwhile, Larry King is still stuck on the whole tax thing and is trying to pin Bob dole down. And I have to wonder whether Larry King has really bad breath or something, because Bob Dole kept making these faces as if that might be the case.

So then Elizabeth Dole is talking about Bob Dole's message and Bob Dole's agenda, and then it's her turn to start reeling off a list of agenda bullet points. And then Bob Dole basically says that without television, a politician can't campaign, which is a pretty scary thing, if you ask me. And then he adds in all the bullet points of what Bill Clinton has done wrong so far. And then Bob Dole is saying how he's glad to be the underdog and that the real campaign is going to kick off with a powerful acceptance speech by Bob Dole at the Republican National Convention.

And then Bob Dole announces that Susan Molinari is going to be the keynote speaker, since she is young and dynamic. And Elizabeth Dole adds that Molinari believes strongly in what Bob Dole stands for. And it's almost at the point where if you couldn't see the TV picture, you might very well wonder if Bob Dole is still in the room or not, since everyone, including Bob Dole, keeps saying "Bob Dole."

Meanwhile, Larry King is milking the whole Susan Molinari thing. And he's like, "That's a big statement about cities." And Bob Dole adds women to that list. And then he starts going on and on about all this stuff he's done for women all these years.

And all I know is that I was taking the M7 uptown bus the other day, and we were going through Midtown. And there were these two women seated in front of me. And in Midtown, there's this big clock which shows a readout of the national debt getting higher and higher. And this one woman is like, "Look, the national debt just gets higher and higher." Like maybe they should take the money that everyone saves with MCI, which is another huge number readout in Midtown, and put that money toward paying off the national debt.

So then she asks her friend, "Who are you voting for?" And the second lady is like, "I don't like the situation we're in one bit. I don't see anyone with any high morals or good ideas, and I don't like Bob Dole. I don't like his stance on issues. Plus, I think he's too old."

And the first lady's like "Too old." And the second lady is like, "Too old. He would be a one-term president." And the other lady is like, "Definitely a one-term president." So maybe Bob Dole should ride around on New York mass transit to get a sense of what he should be doing. And then Bob Dole goes on about what he's done for women, saying, "I've been living with a woman," which was a really, really weird thing to say.

So then we get an advertisement about health insurance sponsored by the Republican National Committee, showing this smirking kid breathing through a tube while his mother goes on about what we need. And then there's a commercial for life insurance featuring these crying statues in the rain. And I don't know that it's such a good idea to remind people about sickness and death when Bob Dole is on the program.

And Larry King brings up Susan Molinari again, like, "Yeah, Larry, we get your little prearranged scoop. Quit working it so much." And Larry King is like, "How did you get involved in this tobacco thing?" And Bob Dole is like, "Just blew in, I guess." And then you realize that Bob Dole keeps looking at himself in the monitor, or else someone is there backstage that he's looking at for cues.

And how sick is it to refer to the undeniable pull of tobacco company money in Bob Dole's pocket as something that "just blew in"? And then Bob Dole says he's not a scientist and so couldn't know that smoking is addictive, which is weird, because later he refers to relatives who were sick due to smoking-related problems. How much evidence do you personally need, Bob Dole?

And then Larry King is like, "Would you tell Americans to stop smoking?" And Bob Dole is like, "Yeah, all of you stop smoking." And Elizabeth Dole qualifies that with "pregnant women and elderly people with respiratory disorders." Where do you think most respiratory disorders come from, Elizabeth Dole?

And then Bob Dole is like, "It's not good for you. It's bad for your health. Don't do it." And having said that, like he was about to go on, but Elizabeth Dole interrupts him and goes, "That's it." And they all laugh. And we get an arthritis pain medication commercial and a denture cream commercial.

So then Larry King is asking Elizabeth Dole about what she's going to be doing as First Lady. And she starts going on about being a supportive spouse. And Bob Dole makes a joke about calling her up for a transfusion. And then he looks at the monitor again. And meanwhile, Elizabeth Dole is going on about going around the country to places where mentally challenged youths are making beautiful products. And I swear to god, if she got any more condescending, I was going to seriously put my foot through the television.

So then Bob Dole goes on the record as not speaking about Clinton's character by listing Whitewater and Filegate as two things he hasn't talked about, even though he just did. And then Larry King brings up more records. And then Bob Dole goes, "Trust."

And then Elizabeth Dole starts going on about how Bob Dole was a poor farmboy whose family moved their kids into the basement to rent out the house to make ends meet. How depressing is that? No wonder Bob Dole has a sour demeanor all the time, since he grew up with no windows.

And then Elizabeth Dole goes on some more, like maybe she should let her husband talk just a little bit. And then Larry King brings up the Jimmy Carter question. "Can you say you would never tell a lie?" And Bob Dole goes, "Yes." And Elizabeth Dole goes, "Yes." Whose question is that?

And then they go on and on about affirmative action. And then Larry King promises to take phone calls for, like, the 50th time. Maybe no one is calling in or something. And then we get that health insurance commercial again and an ad for some ginseng-based energizing dietary supplement to help you feel not so old.

Next, they're talking about the stock market. And we finally go to calls, but Larry doesn't seem to know how to work the phones. And the caller's from Georgia. And I was hoping it was that guy who called up when Jesse Helms was on, thanking him for all his work in controlling blacks, only he didn't say blacks. But it was only some guy asking about running mates again. The one call that they take on the show, and it is some yokel who didn't get that they weren't going to talk about possible running mates.

So finally, we get Susan Molinari on the phone from a restaurant somewhere, gushing on and on about Bob Dole to the point where they probably should have cut her off. And Larry King asks whether Susan Molinari thinks her pro-choice abortion stand is going to be a problem. And Susan Molinari is going on about how, "This is the man to bring the convention together, and there is no greater honor in the world than to speak on behalf of the gentleman currently on your show." You would think Susan Molinari just found God or something, the way she was going on about it.

And all I want to know is does Susan Molinari on the phone to Larry King count as a paid Republican advertisement for Bob Dole, especially when Larry King points out that Bob Dole is the guest who's appeared most on the Larry King show? And then Larry King makes a point of reminding all the news flunkies out there that the two points from his show to remember are "Never lie" and "Susan Molinari." And I don't think November could be any scarier in my mind at this point.

Ira Glass

Well, it is This American Life, the public radio show that is down with the king.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Peter Clowney and myself, with Alix Spiegel, Nancy Updike, and Dolores Wilber, contributing editors Paul Tough, Jack Hitt, and Margy Rochlin.

[ACKNOWLEDGMENTS]

You can read Danny Drennan's writing about 90210 and other things on the web, and we recommend this, http://www.inquisitor com. There's another dot in there. You can figure out where it is. If you would like a copy of this program, it only costs $10. Call us at WBEZ, 312-832-3380. Or email us, [email protected] And have you emailed us? No, you have not.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight by Torey Malatia. I'm Ira Glass.

Bob Dole

I think at this point, it's better to be the underdog. And we believe we're on target.

Ira Glass

Back next week with more stories of This American Life.