378: This I Used to Believe

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass, and the theme of today's show is, This I Used to Believe.

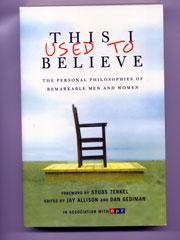

And I have to admit this is just a knockoff of this series that's been running on NPR News called, This I Believe, which in turn, actually is a knockoff of the This I Believe Series that Edward R. Murrow did in the 1950s.

Maybe you've heard some of these on the radio. These are short essays, three minutes long, by famous people and not so famous people very often, about what life has taught them.

The NPR series actually invited listeners from all over the world to write in with their own short essays about what they believe in. And 65,000 people responded. 65,000. I was talking to Jay Allison, who heads the team that sorted through the essays and edited the ones that ended up on the radio, and he he told me that while only 200 of the essays actually ended up on the air, all 65,000 went on to this website that they set up.

Jay Allison

You know, if you go to the website, you can type in any word. I'd started typing in words. I typed like, squid. 11 essays mention squid. Car bomb, 20. Death, 7,000 and some.

Ira Glass

Wait, what were the squid ones? People didn't believe in squid, right? Squid was just an ancillary prop.

Jay Allison

Squid, squid came in--

Ira Glass

We were having squid and I realized--?

Jay Allison

Well, one of the ones I read, was the guy was writing it and had recorded it in a deep sea submersible. He was working, I think, for Greenpeace and he was in the Arctic ocean. And he was looking out the window and seeing squid and writing his essay.

Ira Glass

That guy, of course, wrote about how he believed in cocktail sauce. Not really.

The big things that came up over and over in the essays that people sent in were really exactly what you would expect. People believe in kindness, and the Golden Rule, tolerance, social justice, love, hard work, humility. By the fourth year of the This I Believe series, it got a lot harder to get on the air-- if you believed in kindness.

Ira Glass

Now, I don't want you to get mean about people. Are there some where you and your team read the essays and you just wonder like, "Wow, what were they thinking?"

Jay Allison

There've been some written by people of-- who are very advantaged. And they've written about why they deserve their advantages. And those are somewhat shocking to me. And--

Ira Glass

And who would write this kind of thing?

Jay Allison

Teenagers with money sometimes write about how they deserve it. I was searching for one actually today, and I remembered that they'd mentioned like a BMW, I think in it. So I just did a search on BMW, but then I started scanning them, and a lot of people wrote about a belief in their car. In the brand of car they had. Those essays take me aback a little bit.

One of the essays about cars, the person said, "I believe in having a car as cute as I am." And she believed she was much cuter than her car, her current car. And so she believed that-- I forget whether it was a BMW or an Audi-- but that was the car that she--

Ira Glass

She thought would be as cute as her?

Jay Allison

Yeah.

Ira Glass

Yeah?

Jay says that it's become a popular thing to assign This I Believe essays to kids in high school. There's a whole curriculum around it. And it is clear a lot of the kids do not want to do the essays. Some of them just seem to look around the room and just pick something-- "I believe in pencils,"-- and then start writing.

Jay Allison

There are schools all over this country who are using This I Believe. There is a generation of children who are going to curse our names.

Ira Glass

That's right. They're hearing you on the radio right now. They're sitting in the backseat of the car and then, "Oh, my God. That's the guy! Oh, I hate that guy."

Jay Allison

I know. I hate that show, I can't even believe. We had a kid writing about how he thought he was too cool. He thought everybody, all his friends, were too cool. They were too cool to be, like, courteous. They were too cool to like things. They just wanted to be critical. And he said-- but secretly he didn't want to be like that. And he said, "And the way I'm going to start stopping to be like that is, I'm going to write this essay. Because it's not cool to do."

Ira Glass

NPR News is going to run its last This I Believe later this month. They run the series for four years, which is the same length as the original Murrow series.

A lot of the best This I Believes, a lot of the ones that I like the best, are actually This I Used to Believes. These are people basically talking about how they have changed and what's made them change. Like there's one by a nurse practitioner named Courtney Davis who talked about how early in her career, when patients would go through something really horrible and sad, she was one of those nurses who would try to keep things upbeat. She would keep her voice upbeat. And she would actually try to stay cheerful.

And even when her own mom, she writes in this essay, was dying in the hospital, she continued that way. Saying goodbye to her mom in that cheery nurse voice that she practiced her whole life.

Courtney Davis

I didn't know then that I could have climbed into bed and held her. That I should have wailed when she was gone. I no longer comfort others with false cheer.

Jay Allison

So, I'm wondering you work in radio, and I work in radio. How come we haven't heard from you on what you believe? How come you haven't done an essay for us?

Ira Glass

Well, actually I mean it's funny. I think that I don't-- I say this and it's going to sound a little more dramatic than I mean it. But I'm not sure I believe anything, in that way, that would make for an essay.

Jay Allison

But did you ever, did you ever sit down-- or do you just sort of ask yourself rhetorically from time to time?

Ira Glass

I ask myself whenever I hear the series. I hear you on the radio and I think, how come I'm not on Jay's series? Like, how come I'm not doing This I Believe?

Jay Allison

Are you sure you're not just giving up too easily though?

Ira Glass

I don't know. I think I'm one of those people where like, I had a lot of really strong beliefs about stuff when I was a kid, and I like had a religious phase, and then I had a very strong, like, atheist phase and then I had a very political phase. And I was like politically correct for years. I mean the kind of politically correct where like, when I was in my 20s I went to Nicaragua and I called it Nikh-a-RAH-hua. And you know what I mean? Like, I was horrible. And--

Jay Allison

Did you call it Nikh-a-Rah-hua on the radio, too?

Ira Glass

Ah no. I knew better than that. At least I knew better than that. But you know I mean? Like, and then, just like, I got older and I saw that things seemed more complicated than the way that I'd believed them. And when I poll myself, I'm like, what do I believe in? Well I believe that listening to the radio in the car is the best place to listen to the radio. I've got that. But that doesn't seem like it's worthy of your series. I think it's true. I can defend it, but--.

Jay Allison

How about if something bad happened? Is there something you'd cling to?

Ira Glass

You mean in terms of a belief?

Jay Allison

Mm-hmm.

Ira Glass

I mean, I take comfort in the thought that when things seem really sad it's a comfort to me that well, everybody's going to go through this. Everybody's gone through this. And the problem is that, like, it's too much of a set of truisms to actually be good enough for your series.

Jay Allison

But your show is always looking for a conflict, and something to happen, and for something to change. I mean, maybe even this show is going to be about how something changes. So, possibly you're not interested in things that are static and enduring.

Ira Glass

No, I think that's true. It's funny like I think that's why I like This I Used to Believe. I'm much more attracted to that than to This I Believe because it just has the feeling of like, people are changing. And for me, drama is more interesting than ideas in a way. It's funny, I didn't even know I thought that until now I'm saying, that but I think it's true.

Jay Allison

Maybe you believe in that.

Ira Glass

And there's my essay. You are the master.

Jay Allison

I'm just an editor, man.

Ira Glass

Well, today on our program as I said before, This I Used to Believe. Our show today in four acts.

Act One. Scrambled Nest Egg. About a kid, his parents, and their constant companion. Yes, the US economy.

Act Two. Team Spirit in the Sky. A Texas football coach gets called out on an unusual mission.

Act Three. Me Thinks Thou Doth Protest Too Much. In this case, the me of Me thinks is a teenage girl. And the one doing the protesting is her mom.

Act Four. Pants Pants Revelation. In which we ask the question-- Can two people destroy their chances at love with one pair of pants?

Stay with us.

Act One: Scrambled Nest Egg

Ira Glass

Act One. Scrambled Nest Egg.

Sometimes you don't even realize you believe something until circumstances change in a way that destroys that belief. Alex French went to visit his parents in Massachusetts for a couple days last month.

Mrs. French

We'll go to Cumberland Farms. We're going to buy some lottery tickets. Big jackpot tonight.

Alex French

How much?

Mrs. French

Oh, over two hundred million. It's sort of a cheap way of buying a dream.

Alex French

The French family bailout?

Mrs. French

Yeah, exactly the French family stimulus. So--.

Alex French

One afternoon in early January my mother called me in the middle of the day. I was just laid off, she told me. I could tell she was on her cellphone calling from the car. For the past nine years she'd worked behind the counter of an upscale jewelry store in a mall about 20 minutes outside of Boston.

All of the sudden, the recession was very, very real. Still, I could hear in her voice that she was relieved. She'd never admit it, but she hated her job. So long as your father keeps his job, she reassured me, we're going to be just fine.

Less than an hour later my phone rang again. It was my mother. She took a deep breath and then spoke. Your father has just been laid off, too.

Mrs. French

Sometimes when I think about it, it seems like something of biblical proportions. It's like, it's crazy. I don't know that much about the Bible, but I think there was somebody who had boils, and pestilence, and all kinds of things.

Alex French

What are you talking about?

Mrs. French

Talking about how I feel some days. That everything just happened at once. It was like anything bad that could happen to me or anybody I knew happened. So.

Alex French

I used to believe that recessions only affected people in faraway places like Detroit, Sacramento. I used to believe that my father would work until the day he turned 65 and then stop. There'd be some sort of retirement party and then the next day my parents would move to Clearwater, Florida. Where Dad would play golf and Mom would power walk.

I never imagined that they could be so vulnerable. I never thought I might have to support my parents. It was inconceivable that they might someday have to move in with me because they could no longer pay their mortgage. All that changed when my mom called.

My parents were both 59 years old and for 30 years they've done everything right. Saved money and paid the mortgage on time. When I went back to check on them, everything looked the same. They still have their house and their cars, but there's a sense of danger looming. A sense that if this thing goes on for much longer, my parents' lives might change drastically.

Tom French

You know, I talked to some people about actually going short term over to Iraq.

Alex French

My father has always worked as an engineer. Civil, environmental, hazardous materials, you name it. Tom French has done at all. Go to a mall in the Northeast and there's a pretty good chance that my father helped build it. And when the economy collapsed, the market for shopping centers and high rises went with it, along with my dad's job. I told myself during the train ride up there to stay positive. They'll be fine. You're going there for moral support. But when it came down to talking to my dad about going to Iraq, he ended up comforting me.

Tom French

I've talked to some people who know people who've gone over there and done it. And it's not near as bad as you think it is.

Alex French

Would you really consider doing that? I mean is it that bad that--?

Tom French

Well, I don't want to go to work with a helmet and a bulletproof vest on, but I'd consider it.

Alex French

Being laid off has affected both my parents so differently. My father, with his lifelong career, can't imagine doing anything but engineering. He'd go all the way to Iraq or even Afghanistan to keep doing it. But my mom, on the verge of 60, as worried as she is, also sees this as her chance. Anything seems possible. Massage therapy. TSA training. Jewelry making.

Mrs. French

I'm considering maybe guidance counseling. The other thing I'm considering would be flower arranging. Which, since I love to garden, that's an option. And-- well, we're contemplating a children's book. And I'm hoping to work on a project about Versailles, and what I always want to see is what they don't take you to see. The rooms that have not been rehabilitated or refinished. And I would eventually like to go and take a look, and photograph it, and write about it.

Alex French

Growing up, my parents were never the types that needed to be parented. Our roles were well established. They were the parents. I was the kid. Even for this visit, for example, my father insisted that I make the short trip by train when I wanted to drive, but I didn't argue. Now that I'm here, for the first time in my life I feel like the roles are reversed. I wanted to weigh in on everything from Iraq to the dinner menu.

Mrs. French

Tom, do me a favor. Go on the other side and get me a container of goat cheese.

Tom French

OK.

Alex French

Goat cheese?

Mrs. French

Yeah. Goat cheese.

Alex French

Isn't that a little-- kind of a little bit of a luxury item for two unemployed folks?

Mrs. French

Yeah, but you know it lasts for a few weeks. It's OK. It sort of makes-- we don't eat out at all, so it makes staying in pleasurable. And so, buying a $4.50 container of something is a lot cheaper than going out and buying and having an $8.00 salad.

What do you feel like eating this week?

Tom French

Soup.

Mrs. French

Soup. Gruel?

Tom French

Day-old bakery.

Alex French

They're joking around, but the most shocking thing that I noticed during my visit was how little food there was in the house. Growing up, it was such a comfort, a feeling of plenty when you opened the refrigerator. Now, it's not quite like a bachelor pad refrigerator, with just an empty bottle of ketchup. But it's not far from that, either.

Tom French

Yeah. No seriously, though. I mean, we're still eating pretty good. But if this thing goes on for an extended period, we're going to have to cut back even more. If this thing goes like four months or something and we're really ripping into savings to do that we're-- it's going to get cut back even more than it is already.

Alex French

My parents are handling this as well as they can. It's easy to see that the worry is getting the best of my father. He tells me he's having trouble sleeping. Lays there in the dark, staring at the ceiling 'til 1:00 AM or 2:00 AM, wondering how much longer he's going to be able to pay the bills. The unemployment benefits my parents receive barely cover expenses. Or when he and my mom are going to have to start digging into their savings.

Tom French

You know we went to take a little one-hour seminar down at unemployment to talk about the benefits and about looking for jobs.

Alex French

I mean is there part of you that feels like-- I mean if you did qualify for something like welfare or for food stamps, I mean, is that something that you would do? Or is there a part of you that feels like, no like I'm-- I mean do you have too much pride for that, or--?

Tom French

No I don't think so. I mean it's like the stimulus. I mean, anyway my attitude is, is with unemployment and the stimulus and all these other things. I mean, I paid a lot of money into the system over the years. And I'm sure there's a lot of people that've paid more in than I have who've never taken anything out. But I mean, I've paid a lot of money into this system for a lot of years so, I'm in a situation, I didn't do anything wrong. I'm in a situation where I need some of that back now to get me through a tough spot. And if I'm entitled to something by the law, then I'll take it. Why not?

Alex French

When you say I didn't do anything wrong, what do you mean by that?

Tom French

I didn't do anything wrong. I went to work every day. I worked hard. I did a good job. Obeyed the law. I paid my taxes. I did everything I was supposed to do. I didn't do anything wrong. This is a painful process we're going through now, but it will be over.

Mrs. French

We decided we would tell people that we were retired. And when we go back to work, we'll tell them, well we didn't think retirement was so great, so we thought we could go back to work.

Alex French

At this point, they don't need me to step in and say anything. I should stay calm, offer support, shut up. I don't tell them that I'm also losing sleep worrying about them. All weekend it's hard to know what to pay for. I don't even try to step in and pay at the grocery store. But they let me take them out for dinner and two lunches, and I pick up some odds and ends for them at the Family Dollar. I buy their lottery tickets, too.

Ira Glass

Alex French in New York.

[MUSIC - "WORRIED MAN" BY JOHNNY CASH]

Act Two. Team Spirit in the Sky.

Just before Christmas the coach of a high school football team in Texas did something that football coaches pretty much never do. He urged half the parents at his school one Friday night to root for the other team. And they did it. His school was a Christian high school called Grapevine Faith. The other team was made of juvenile offenders from the high school at a state penitentiary. Kids whose families never came out to games. Lots of people in these kids' lives had given up on them.

But this one night, hundreds of parents and kids learned their names and rooted for them when they made their plays, and actually rooted against their own team. These kids from the penitentiary ran onto the field through a spirit line. You know that thing where there are two lines of fans? They had cheerleaders cheering for them. This clip is from a TV story done by the NBC affiliate in Dallas-Fort Worth.

Football Player

I want you all to line up in line, they're making a spirit line. I like say, what cousin, what'd you say? Can you repeat that? When I ran through this like I felt like it was just like something like angels or something that's all I felt cause I was just running through as fast as I can I just feel the wind rushing my face.

TV Announcer

That feeling of being unleashed lasted throughout the game and so did the cheers.

Football Player

I remember when was making like a play, I made a tackle and people yelling my name, I'm like, I don't even know these people.

Ira Glass

This story became one of those things that people linked to all over the internet, talked about on discussion boards, that thousands of moms forwarded to thousands of grown kids all over this country. And it got lots of press. The coach from the Christian school was on ESPN and the 700 Club, and all kinds of radio and TV. The NFL Commissioner invited him to be his guest at the Super Bowl.

And on Christmas morning, a woman named Trisha Sebastian saw a link and read about it in Rick Reilly's ESPN column online. She was alone. Her family was on the other side of the country. She was in an apartment in New York filled with her own moving boxes, in the kind of mood where this just got to her.

Trisha Sebastian

One of the details from the story that just really killed me was that when they go back to the school, they got to be shackled when they get into the bus.

Ira Glass

That they had to go into handcuffs when they get on the bus.

Trisha Sebastian

Handcuffs, when they get back into the bus.

Ira Glass

And so she decided to write an email to the coach at this Christian school who organized this nice thing for these kids. A guy named Chris Hogan.

Trisha Sebastian

And I said, Dear Mr. Chris Hogan. Thank you for being a good inspirational leader to your players and to your players' fans by encouraging them to think of those who are less fortunate than they. I'm a very lapsed Catholic, leaning towards agnosticism, who has seen too many people who claim to be Christians behaving in a very un-Christian way. You are one of those bright few who embody what being Christian means. And I'm glad that you're in a place where you can show young children an example of being a good Christian. Thank you.

Ira Glass

Now there's a time stamp on that because it's an email. What time did you send that?

Trisha Sebastian

6:32 in the morning, on Christmas day.

Ira Glass

And that afternoon, much to her wondering eyes did appear a reply, time stamped 12:09 PM.

Trisha Sebastian

So he wrote to me, and this is what he said, "Thank you so much for your kind words. Trisha, I've received literally hundreds of emails over the past few days. And yours is the first I've responded to. Yours reached out of my computer and gripped my heart. When I read it, my spirit was pressed to answer you first, when I'd read that you were leaning towards agnosticism because of the actions of Christians.

"Let me encourage you to not make a judgment about God, based on the actions of men. My heart is heavy to think of you walking away from a God who loves you so much. Trisha, would you consider speaking, even if it's by email, about the idea of God? I do not think your sending me the email was coincidence. I expect to hear back from you, young lady. Thanks again for your exhortation. Bless you."

Ira Glass

It's interesting that at the end he gets all-- right back to me young lady, like you're one of the kids in his program.

Trisha Sebastian

Yeah, I know. Which I thought was kind of cute.

Ira Glass

She wasn't really sure, though, if she wanted to hear his pitch about Christianity. But she thought that at least she owed him the courtesy of a reply. So she wrote back. Mainly to clarify that she hadn't become agnostic because she'd met hypocritical Christians. She didn't think so badly of Christians.

She told him that she'd been raised Catholic and she really did used to believe in God. But she started questioning her faith three years ago, when a close friend of hers named Kelly, who was just 32, was diagnosed and very quickly died of colon cancer. Tricia wrote this long heartfelt email explaining all this, in which she politely declined the coach's offer and closed with quote, "Thank you again for being such a good man and a good Christian." And that was that.

Until three weeks later, Coach Hogan wrote to her again. "I know we had finished our conversation," he said. And he'd been fine with that. But there was a snag. God kept waking him up in the middle of the night, putting her very sincere emails into his head.

"I have tried to ignore it for several weeks," he wrote. "But I need some sleep. In prayer this morning, I decided this isn't going away until I make contact with you. I know God has put something on my heart to tell you."

Trisha did not know what to do. ever since her friend died, her religious beliefs were set.

Trisha Sebastian

I'd pretty much thought like-- come to the conclusion that there's no God out there. Things happen. This thing happened, and is nothing special.

Ira Glass

And you didn't want to get into it.

Trisha Sebastian

I didn't really-- didn't want to get into it. It's like part of what made life after Kelly's death a little more bearable was knowing that it just happened. That there was no reason why.

Ira Glass

And was part of it this guy saying to you, OK God has been talking to me about you and he's waking me up in the middle of the night, and was there part of you thinking like, oh no, like what if that's real? Like, what if this is actually the way that God is trying to get to me?

Trisha Sebastian

Yeah, I mean like a lot of it's like, oh crap, what's he going to say? Here's this guy who is a stranger, who's telling me, "God has something to say to you." OK, you can sometimes ignore your friends, but like not this. This is kind of weird, you know?

Ira Glass

What was especially weird is that Coach Hogan was basically just this random guy from the news. Trisha said that it was like, as if Captain "Sully", who landed that US Air flight on the Hudson, suddenly called her up to say God told him to especially save her.

And finally, Trisha decides that she's going to do it. And asked Coach Hogan if he would be willing to let her tape this conversation, and maybe play a little bit of it here on the radio. The coach feels that it's his mission to witness for God wherever he can. He sees his work in the high school as part of that. He teaches Sunday school. He talks about God with people all the time, he says. So he had no problem with that all. So, these two people with very different beliefs got on the phone together.

Chris Hogan

This is Chris Hogan.

Trisha Sebastian

Chris Hi! This is Trisha, how do you doing?

Chris Hogan

Hey Trisha how are you?

Trisha Sebastian

I'm OK. So, the reason why I really wanted to talk to you is because you had mentioned that God was speaking to you and telling you that you needed to talk to me. I'm just wondering what you think God's message to me right now is.

Chris Hogan

OK. Well, it's interesting because your email, as soon as I read it, my gut just turned over and I could just feel pressed in my spirit. And later that night, in the middle of the night, I had this really strange dream. And I woke up and there was your email in my head, and I thought well, that's strange. So I go back to sleep and it happens about three hours later. He continued to wake me up and what's interesting? He kept waking me up at the exact same time.

Trisha Sebastian

Wait, what time?

Chris Hogan

He kept waking me up every single night at 1:30. Every single night. And the interesting thing is when I would ignore it, he'd wake me up again at 4:04 in the morning.

Trisha Sebastian

OK that's kind of weird because for the last couple of weeks, I've been waking up at 3:00 in the morning for no reason at all.

Chris Hogan

Yeah. It's interesting because the longer I prayed about it, I felt like that he was trying to get me to tell you that everybody has faith in something. And if you don't have faith in like the biblical idea of God, then you must have faith in something else that you think, well then this is true. And I think my spirit is just telling me to tell you, don't settle for that.

Ira Glass

For the next hour, Coach Hogan tried to convince Trisha that God exists using all kinds of arguments. The first and second laws of thermodynamics. And arguing against the Big Bang, and evolution. It was the kind of conversation that led, sort of inevitably, to questions like why does God give us free will to believe in him or not? Or this snippet will capture some of the tone of things for you. They're talking about whether the Bible is right when it says that some things are objectively good, and some things are objectively true, and other things are objectively evil. Some things are just wrong.

Chris Hogan

If you say good is only people's opinion. It stems from our own-- you define true for you and I define true for me, then how do you reconcile that with Hitler saying it is true that if we can eliminate Jews and other people on the planet that it'll be a better planet because we're a superior race. And of course he gets his worldview from Charles Darwin.

Trisha Sebastian

Right, wait. Wait, wait, wait, wait.

Chris Hogan

So if Mother Teresa gets to choose good and Hitler gets to choose good, who's right?

Trisha Sebastian

I'm sitting here listening to you. Up until you brought out Hitler I was completely with you all the way, and all of a sudden you're throwing Hitler out, and I'm all-- and I'm thinking to myself, where is he going with this? How can I--

Chris Hogan

Well, and you know how I brought Hitler out? I'm just using your logic.

Trisha Sebastian

Yeah, but did you have to go all the way out there?

Chris Hogan

And I'm trying to demonstrate that what you're saying doesn't work. When you take it to its logical conclusion, what you're saying doesn't work.

Ira Glass

When Trisha tries to talk about her friend Kelly, and how her faith changed when Kelly got cancer, Coach Hogan tells her about his Aunt Gina, who had faith. And when she got cervical cancer, it miraculously went away.

Chris Hogan

Somehow, a lady who was "over 90% dead", quote unquote, now has not one ounce of cancer.

Trisha Sebastian

OK, so my question is why did your aunt survive and my friend die?

Chris Hogan

OK. Now let me tell you this, Trisha. Do not, for an instance, believe anybody who can tell you why that is. Including me, any pastor, any priest, anybody, because that is an area designed for God.

Trisha Sebastian

But there were a lot of things that, when we found out that Kelly had cancer, I prayed. I prayed so hard. I prayed for-- I prayed like I've never prayed before. Because I was taught growing up, that if you prayed to God, God would answer your prayers.

Chris Hogan

Did you know that's false? Let me give you a for instance. Suppose I prayed today to win the lottery. He might not answer that prayer, and it might be for my own good. He is God. He knows everything, he's all powerful, he's all good, he's all knowing, he's omniscient. Obviously, he's superior to some Texas high school football coach, right?

Ira Glass

When they finally do get off the phone, they're both friendly. But they both also seem a little disappointed. Trisha and I sit down to talk about how she thinks it went.

Trisha Sebastian

It was totally not what I expected. I was thinking, OK, here is my chance to speak to a man who really believes in God and find out the answers to these burning questions I have. You know, I've been struggling with this grief that I feel over my friend's death. And I thought that he would be able to counsel me and console me. And what happened instead was he basically brought out argument after argument, like he was saying that the theory of evolution is contradicted by a seventh grader's text book, and just--

Ira Glass

Oh, I see. He was trying to argue with you about the existence of God instead of trying to comfort you.

Trisha Sebastian

Yeah. I think that was it. There were times when I'd completely warmed up to him, and then he says stuff like what he said earlier about how Hitler and truth-- One of the jokes that a lot of my friends have is that the minute you pull Hitler out in any argument, you automatically lose. And that completely turned me off towards him. And now I'm still left with all these questions.

Ira Glass

Is there any small part of you that thought he might be able to put the religious message in some way that would finally make sense to you? Like he would say to you--

Trisha Sebastian

I was-- yeah.

Ira Glass

You did hope that?

Trisha Sebastian

I really did hope that. Deep down, and I've said this to so many friends of mine, I really want to believe again.

Ira Glass

So you did want him to bring you back to God?

Trisha Sebastian

Maybe. Possibly. Most likely.

Ira Glass

But just the way he was doing it wasn't a way that really talked to you?

Trisha Sebastian

No. no.

Ira Glass

I wonder if the problem with that was just the way he was going about it and the arguments he was using. Or I wonder if really there's nothing anybody could actually say to make you believe this thing that now you find yourself not believing?

Trisha Sebastian

I don't know. If someone were to just tell me, this is why Kelly died and they were able to relate it back to God, I would probably respond to that better.

Ira Glass

And then when you asked him this, what did he say?

Trisha Sebastian

We never got to that point. We never got to that point. I couldn't get him there. I couldn't ask him the questions I really wanted to ask.

Ira Glass

But what if it's as simple as, for people who believe in God, God takes different people at different times. And that doesn't mean that God doesn't have some plan for you, you know?

Trisha Sebastian

See that makes more sense to me than anything he ever said in our conversation.

Ira Glass

Well that's very sad, because I actually don't believe in God.

Because her main question wasn't really discussed very much in that first conversation, she set up another call with Coach Hogan. And she asked him if this time I could get on the line with them, mainly just be sure that everything stayed focused and she got the actual answers that she wanted. Again, the coach was fine with that.

Ira Glass

So the reason why we're calling is because after you talked to Trisha last time, Trisha said to me that the main thing she felt like she wanted an answer to, somehow it didn't really come up. And really it comes down to her friend Kelly.

Trisha Sebastian

Sure.

Trisha Sebastian

It doesn't make any sense for someone like me to still be here when someone like Kelly, who was such a good person and who spread so much good throughout the world in her small, own little way. It just doesn't make sense.

Chris Hogan

Sure. This is the most common question that folks who are anti-God ask. I don't know if you guys know that or not, but this is the most common objection to God. Why does God allow bad things to happen to good people? You have to understand that sin entered the world through one person, Adam. Now, if you read what the Bible says happened as a result of sin, every single person who's ever been born is born into sin. Do you understand the Garden of Eden and the condition we have now are two different scenarios. One was pre-sin, one is because of sin.

Trisha Sebastian

So I'm sorry to break this into a blunt way. So you're saying that cancer is caused by sin?

Chris Hogan

I'm saying anything on this Earth-- all the diseases, all the bad things that are here-- are a result of sin. That's what the Bible teaches. Your friend Kelly, I'm not saying that she sinned to get cancer, I'm saying we're in a fallen world.

Ira Glass

All through Trisha's conversations with the coach, I felt like I was hearing over and over why it is so hard for religious and nonreligious people to communicate sometimes. The premises are just so far from each other. When the coach says we live in a fallen world, that explanation is a comfort to him. It's comforting to think that he doesn't have to make sense about every injustice and every terrible thing that happens on this Earth. It's messy on this Earth. Things will be better in heaven. But because God understands the details of why one person with cancer lives and another person with cancer dies, he doesn't have to. And the coach has a hard time, I think, seeing why this explanation isn't a comfort to Trisha. As soon as he understood that what Trisha wanted was an explanation for Kelly's death that would help her feel better about that death, this is what he said to her.

Chris Hogan

Well I can tell you this. Your friend Kelly, Trisha, didn't do anything necessarily to deserve that. I'm not saying that in the least. But I am saying she lives in a fallen world.

Trisha Sebastian

Well I think we all do.

Chris Hogan

There's no question. There's a fallen world. And the world has fallen, because people have chosen evil. And so, as a result, sin entered the world, and with sin comes a lot of things. And they're going to affect people. But the great thing is, this is not where eternity rests.

Ira Glass

Trisha is that helpful to you?

Trisha Sebastian

A little bit. I'm getting an answer. And it's the answer that he agrees and believes in. But it's-- I don't think I'm there yet.

Ira Glass

Coach Hogan told us that he was going to feel really sad when he got off this phone call. But in the weeks that have followed, he has accomplished this-- Trisha has been thinking about God a lot more, she says. She doesn't really believe just yet, but she says she's open to it.

Coming up. What happens when you learn that the thing that you believe is the source of your personal power and magnetism is pretty much the opposite. That's in a minute. From Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International, when our program continues.

It's This American Life, I'm Ira Glass. Each week in our program, of course, we choose theme and bring you different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's Show-- This I Used I Believe. We have stories today about people doing that all too uncommon thing of reexamining their beliefs and coming to new conclusions.

We've arrived at Act Three of our show.

Act Three. Methinks the lady doth protest too much.

You know, parents have an advantage over their children when it comes to inculcating them with a set of beliefs. With their set of beliefs. Let's be honest.

They're taller, first of all. And they're adults, capable of argument. Persuasive argument, hopefully. But if none of that works, they also control allowances, weekends, basically everything in the kid's life.

Molly Antopol was 13 when she confronted the full strength of this power imbalance.

Molly Antopol

When I was in seventh grade, my social studies teacher led our class in a rousing debate over Roe v. Wade. I had never heard of abortion. I barely knew what sex was. And my immediate emotional reaction, and the position I backed enthusiastically in the debate, was that it seemed to me like murder.

That night over dinner, when my mother asked what I'd done in school I told her about the class discussion, and about my stirring defense of the pro-life position. My mother, a longtime liberal and women's rights advocate, had never looked so crushed.

"Murder?", she said.

And when I said yes, she repeated it again and again like a mantra. Then she set down her fork and stared at me, as if really noticing her daughter for the first time. "You're saying a woman shouldn't be allowed to decide what she does with her own body? With her own fetus?"

"Exactly," I said. I had no clue what a fetus was.

"And you're saying that if a woman's raped, or molested, or whatever she shouldn't have the right to terminate the pregnancy?"

As my mother continued to lecture, she wouldn't even look at me. She seemed to be staring straight past me at some indeterminate blank spot on the wall. And I truly understood, for the first time, what it meant to disappoint her. I swallowed a pain in my throat, but it came back up again. And finally she stood up and dumped her dishes in the sink. Then she faced me and said, "Go to Siberia for half an hour and think about what you just said."

"Siberia" was my bedroom closet. It was where I was sent for timeouts when my mother thought I needed to think things over. My mother was not the type to respectfully agree to disagree. She came from a long, steady line of organizers, who broke the law in an effort to change minds, starting with her great-grandparents, Trotskyites in Ukraine.

That night in Siberia, squeezed between coats and old board games and camping gear, I did think about abortion. And it still seemed to me like murder. But I knew my mother would never let this go. And I knew it was up to to me to end it for both of us.

If I let her win, I could crawl up on the sofa and watch Kristi Yamaguchi skate in the Olympics. That was all I wanted to do that winter. But when I returned to the kitchen, my mother was replacing the Indian takeout menu on the refrigerator with a bumper sticker that read, "Keep your rosaries off my ovaries."

"What are rosaries?," I said.

"Christian prayer beads," she said.

"What are ovaries?"

"The part of a woman's body that makes eggs."

"Why would someone put rosaries on their ovaries?"

"It's a metaphor," she said. "For Christian fundamentalists who try to force their views on other people."

"Like you are?," I said. I spent the next half hour back in Siberia.

[MUSIC - "QUE SERA SERA" ON SITAR]

And so the re-education began. Over the course of that winter my mother made me wear buttons to school-- "No Mandatory Motherhood. Pro-child. Pro-choice." which I removed and slipped into my backpack as I walked into class. She pulled feminist paperbacks off our cinder block and plywood shelves, and read from them aloud.

My mother even took me across town one early February morning where we, along with other members of her women's group, helped escort pregnant women into an abortion clinic. Together, we marched toward pro-life protesters who sat outside the building in lawn chairs clutching their own signs, one depicting a baby that looked more alien than human. Tiny and shriveled and blue.

"I hate that sign," my mother said quietly. I looked at my mother and she looked back. At that moment she seemed more tired than anything else and I wanted to cut her a break.

"You were right," I blurted. She stopped walking.

"Right about what?"

"About abortion," I said. "About everything, OK?"

"Say it then."

"Abortion should be safe and legal," I said. I could tell she didn't believe me.

"Say it again," she said. And I did.

I had hoped that by giving in, things would return to normal. And they did for a few days. My mother went to work. I went to school. And in the evenings, we sat up late eating takeout and watching recaps of the Olympics.

Then came my birthday. For months I'd been begging for a pair of Riedell figure skates. I pictured myself impressing the skinny, dark-haired guy behind the snack stand at the ice rink with my triple salchows. I'd pointed the skates out to my mother at the mall, and on every female Olympian we saw on TV. But when my mother strode into the living room with my present, I felt my heart cave.

There was no way those skates could fit inside the thin manila envelope she handed me. I tore it open and found a letter from the Women's Reproductive Rights Assistance Project thanking me for my generous donation.

"What is this?," I said.

"An abortion," she said.

"For a 13-year-old girl who was gang-raped downtown, paid for in your name." She said it with a hint of pride in her voice. "Happy birthday."

I stared at her. This was my present? She hadn't even bought me the abortion.

"This girl doesn't have anything," my mother continued, "No home, no money, no supportive, wonderful mother who understands that the last thing she needs in her life is a baby. And this organization gives her the chance to change things for herself."

"Terrific," I said. "I didn't know Hallmark made a Happy Abortion card." I stuffed an entire cup cake in my mouth, knowing this was just the beginning.

I was right. Three days later a letter arrived from Amy, the girl whose abortion I had funded, thanking me for making her life a little easier. To this day I don't believe the organization would have allowed us to have contact, or encouraged her to give up her anonymity. And no matter how many times she denies it, I still think it was my mother who typed up that letter. But that evening, I was too stunned to argue.

"Write her back and then show me the letter," my mother said.

And when I told her, "I don't know what to say," she sent me to Siberia with a notepad until I came up with something.

It was Friday night. And as I crawled into my closet, I envisioned my friends at the ice rink and resented that I had to write Amy. As if she were my pen pal, or a child in Africa whose meals I was funding for $0.10 a day.

"I wish you all the best," I scribbled. But that felt as if I were signing some stranger's yearbook. What difference did it make what I thought? I hated that my mother was so bent on drafting me to her side when, at 13, I knew my views didn't matter. But the thing is, they did matter. To her.

What I realized spending every weekend for an entire winter with my mother, was how upsetting it must be for her to be this single mother, living in a tiny one-bedroom stucco apartment. Working two jobs to support a daughter who didn't even get where she was coming from, who maybe didn't understand her at all. So I tore off a new page.

"You should really be thanking my mother," I finally wrote. It still felt like the fakest thing on Earth to correspond with a girl I didn't know, and who probably didn't even exist. But even then I knew who this letter was really for.

I continued, "She's the one who taught me that the denial of safe abortions can threaten your health. And that your reproductive freedom is a fundamental human right. "

Fundamental felt too businesslike, so I crossed it out and tried again. And as I sat back and worked through the next line, I wondered if any of these thoughts would begin to feel like my own. They didn't yet, but I was just getting started.

Ira Glass

Molly Antopol. she teaches creative writing at Stanford University, and she's working on a book of short stories and a novel.

Act Four. Pants Pants Revelation.

Well, we end our program today with a love story about two people with very different, opposing beliefs. Beliefs, I believe, that could never be reconciled. One of them was for, one was against. One was pro. One was con.

This story begins in 1990. Joel and Kate were both working in a psychiatric hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. From the moment they met, Joel liked Kate, Kate liked Joel, but it took them awhile to kind of figure that out. And while that was happening, Kate spent a lot of time thinking about how to get in good with Joel.

Kate Porterfield

I mean the embarrassing thing is that basically I would check the schedule at the hospital each week and look ahead to the seven days and find shifts when I was working with Joel. And then plan my outfits accordingly, because I really wanted to look cute. And one of the things that I always relied on was that I had this pair of jeans that I thought looked really good on me. And I would purposely save the jeans after laundry to the day when I knew I was going to be working with Joel so that I would look real fine in front of Joel.

Joel Lovell

She did have this one pair of pants that I wasn't totally crazy about. The pants seemed not in fitting with the rest of her. And so it always sort of threw me for a moment.

Ira Glass

Describe the pants please.

Joel Lovell

Well, they were acid-washed.

Kate Porterfield

They were awesome. I loved them. They were acid-washed denim. Sort of speckly white. Tapered at the bottom at the ankle. And a little bit, not balloonish, but a little puffy.

Joel Lovell

And they ballooned out in the thighs in a sort of jodhpur-y kind of way. And the sort of really crazy part was what happened up near the top. They had this fold over front area?

Kate Porterfield

The feature of the pants that I thought made them really amazing is that they had at the top-- you have to try to picture this-- they kind of came up pretty high on your waist. Like a good, gosh, four inches above your belly button?

Ira Glass

OK.

Kate Porterfield

But at the very top of them in the front, they rolled over into this flap. This big flap. And they were just, they were very cool. There was a lot going on in these jeans.

Joel Lovell

You know, I don't want to pretend like I'm some incredible fashion maven. I'm not. But these were not a good-looking pair of pants.

Ira Glass

What was the original context of these pants? I'm picturing a Boy George concert. Maybe The Cure?

Kate Porterfield

Exactly. Yeah, you got the timing right. I think I bought them-- I remember now, I bought them at a store in Boston. Bought them probably late '80s or '87 something like that, in this store that was very kind of just '80s Boston clothes. It's just a certain look. I mean, it's definitely got a little of the Bananarama thing going on, a little bit of Boy George.

Ira Glass

Yeah?

Kate Porterfield

But I'm still dragging them out at this point, because I'm thinking they look so good on me and I like them so much.

So, one of my strategies was I'd see if we were working an evening shift together, because an evening shift meant we were more likely as a group of people to go out for a beer after. And that was like, that would be a golden opportunity to wear the pants. Because you'd wear them and then you're going to be out afterwards, in a bar. Just like I've got a whole evening of these pants at that point, and I know I'm going to be just gold, you know?

Ira Glass

Do you remember any key dates where you wore the pants?

Kate Porterfield

A key date? The first night when it became apparent that Joel was interested me, was a night we had an evening shift and then a bunch of us went to this bar. And the group started dwindling and dwindling and dwindling, until it was left with just me and Joel. And I was wearing-- I was wearing the pants that night. And it was a very successful night because that was the night when he kind of, sort of was making eyes at me, and I could tell this is going to go somewhere. He's going to ask me out.

Ira Glass

Really? So the actual night that you turned the corner with your husband and the father of your child, you were wearing the pants?

Kate Porterfield

I-- Yes, I was. Yes, I was. That's right.

Ira Glass

That was the pivotal night in which your life turned from what it was to what it is?

Kate Porterfield

That's right. That's right. Well said.

Joel and I began dating. And I'm just very, very happy at this point, because he's just a wonderful person, and I can't believe it's worked out, and we start dating. So, we're going along, and we're working together and dating. And it's reached, I'd say we're at about four months at this point.

So we've been dating for about four months, but it's at that point where relationships get where I think it's kind of like, you know that-- I mean it's not super serious yet, but you know that this is going to keep going and this has a lot of potential. You're both clearly very into each other. So we're at that point, about four months, and Joel was actually over at my apartment.

Joel Lovell

Kate's in her bedroom, at her apartment going through her clothes and figuring out which ones she should keep and which ones she should give to Salvation Army.

Kate Porterfield

And I opened up my drawer where I keep my pants and lifted the stone-washed pants out of the drawer, not at all because I was considering sending them to Salvation Army, but only because I had to move them to find the pants on the bottom of the drawer that of course I might send to Salvation Army. And as I pull the pants out of the drawer, Joel, sitting on the bed, kind of sat there a minute and cleared his throat and said--

Joel Lovell

Um, you sure you want to keep those pants? And she sort of stops and looks at me and says, "Well, you know. Yeah, I-- of course, I mean I, I think I do, why?"

And so I say, "Well, you know those-- I just think those pants are maybe a little bit out of style now."

Kate Porterfield

He said, "Well, do you think maybe, do you think maybe they're just not in so much style anymore?"

Joel Lovell

And as the words are coming out, I see Kate's face flushing. Becoming pinker, and then red.

Kate Porterfield

And I was like-- WHAT?

Joel Lovell

She's sort of holding them in her hand and looking at them, and looking at me, and looking back down at them. And I realize these aren't just another pair of pants. These were the-- these were the special pants.

And then I-- it's a very uncomfortable situation for me because, a, again, I'm not a particularly fashionable guy myself so I probably don't have any right saying this to anybody. But then, b, this is the woman who I've really fallen in love with and this is like one of the first moments when I've had to say to her, there's something about you or-- there's something connected to you that I don't like.

Kate Porterfield

I couldn't believe it. That these pants that had like, I've been purposely wearing in front of him for so many times, and I thought had done such a good job for me, and he was now saying I should put them in a bag and put them on the curb, basically.

Ira Glass

You thought that the pants had actually done a job on him? You thought the pants were part of your arsenal and part of your power over him?

Kate Porterfield

They were-- yeah, arsenal. Exactly. They gave me confidence, which gave me some, I think, some degree maybe of attractiveness to this person who ultimately I was trying to attract. Because clearly, when I was walking around in those pants, I was feeling pretty confident. I thought I looked great.

Ira Glass

Do you think you could have gotten Joel without the pants?

Kate Porterfield

Wow. Gosh. I hate to even have to think about it, Ira. I don't know.

Ira Glass

You think the pants were that big of a factor?

Kate Porterfield

I don't know! I don't know. I mean, it's been 11 years, but maybe those pants had something to do with it. You know, I'd have have to ask him. I'd have to ask him.

Joel Lovell

I would have fallen for her if she were showing up in Garanimals every day, say, or leisure suits or something. I mean, as anybody knows who's ever fallen in love, you idolize the person you're falling in love with. And they can, in those early days particularly, they feel perfect to you. And then you start asking yourself all sorts of questions. All sorts of insecurities come up. Why would this perfect person necessarily fall for me, and accept me and want to be with me?

But then when you discover a chink in that person's perfection, when you find a flaw-- in this case Kate had bad taste at least in this one pair of pants-- then it somehow makes you feel a little bit more comfortable. You feel like, well, maybe I do have a chance here because, God, I mean those pants had a chance with her.

Ira Glass

Joel Lovell and Kate Porterfield. Since that story originally broadcast on our program in 2001, their family has grown to three kids, two adults, no acid-washed jeans.

[MUSIC - "VENUS IN BLUE JEANS" BY JIMMY CLANTON]

Well, our program is produced today by Lisa Pollak and me, with Alex Blumberg, Jane Feltes, Sarah Koenig, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp and Nancy Updike. Our Senior Producer is Julie Snyder. Production help from Andy Dixon. Seth Lind is our Production Manager. Music help from Jessica Hopper. Special thanks today to Judy Hoffman, Andrew Solomon, and Simon Johnson. And thanks today to the staff at This I Believe, especially Viki Merrick John Gregory and Dan Gediman.

The old 1950s-era This I Believes are going to be running now on Bob Edwards' weekend show. And there's a podcast and all 65,000 essays at this thisibelieve.org.

Jay Allison, who I talked with the top of this show, is moving from This I Believe to producing a brand new show for Public Radio, The Moth Radio Hour, which is going to be like The Moth story-telling podcasts that we've excerpted a number of times here on our show, but a whole hour this fall.

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International.

And we are just days away from our one-time only live cinema event, where we are doing our show onstage with Dan Savage, Mike Birbiglia, Joss Whedon, Starlee Kine and others and sending it out live to movie theaters all across the country, this Thursday, April 23. You don't have much time. Tickets at thisamericanlife.org.

WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia, who really does not care if public broadcasting collapses in the current economic environment. He's got bigger plans.

Mrs. French

I'm considering maybe guidance counseling. The other thing I'm considering would be flower arranging.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

[MUSIC - "VENUS IN BLUE JEANS" BY JIMMY CLANTON]

Announcer

PRI. Public Radio International.