68: Lincoln's Second Inaugural

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

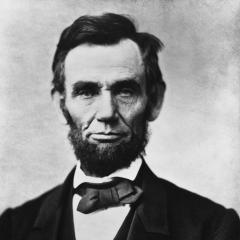

From WBEZ Chicago and Public Radio International, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Our story today begins in 1865 and ends this year, today. The moment in 1865 where we start is on March 4, the day Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. I don't know if you've ever read this speech, but it's this incredible document, just four paragraphs long.

At the time that he delivered this, the Civil War was ending, over a half million Americans dead. And Lincoln uses the speech to ponder the question, why have we been visited with this war. Here are his words.

"Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude or the duration, which it already has attained. Each looked for an easier triumph and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God. And each invokes his aid against the other. The Almighty has his own purposes."

And at this point in the speech, Lincoln posits this incredible image that slavery is a kind of original sin on this continent, an original sin for which all Americans must pay. He says, "Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with a lash shall be paid with another drawn with a sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be said, 'The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.' With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we're in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Well, today on our program on this Fourth of July weekend, we raise this question. How're we doing absolving ourselves of our original sin? To answer that, let's fast forward to the 1990s.

Eliyahu Miller

You hear how I'm talking now? I don't talk like this when I'm around my friends who don't speak like this. When I go to a school like this, everyone is speaking like this. So I have to do my best to blend in, which I kind of do pretty good. I pretty much have everybody thrown off about me. They pretty much know nothing of where I come from.

Ira Glass

This is Eliyahu Miller. When I recorded this, he was a sophomore at a Chicago high school named for Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Park, in a rich neighborhood in Chicago's mostly white North Side. Eliyahu rode the bus for nearly an hour a day to get there from his home in a neighborhood on Chicago's mostly black, mostly segregated South Side. One measure of how far we have to go in healing the wounds of the past is the distance Eliyahu had to go between home and school.

Eliyahu Miller

It is hard on a person to come to Lincoln Park. And your friends, they have $50 in change and then some. And they have these expensive things. And then you go home, and you're slapped in the face by reality. That's why I spend so much time at school. I hate to go home.

Chris

As for me, my whole life, I haven't been prejudiced. And up until this year, I've been totally free of all prejudice. But it's just gotten to the point where I can't hold it back anymore.

Ira Glass

This is Chris, a senior at Lincoln Park the year I interviewed him. America's biggest experiment in integration, integrated schools, left Chris intolerant mostly because of tense, little interactions he used to have all the time with black students. Some of them were his fault, he said. Some theirs.

Chris

There was an incident recently where I was trying to go out of a door that someone was standing halfway in, halfway out. Said, "Excuse me." So I went through.

Guy started saying, "All these doors and you had to go through this one." I said, "That's right. Yeah." So he starts saying, "You better keep walking, white boy. I'm going to beat your ass," and all this.

I just stopped and said, "Excuse me?" And he said, "You heard me. I'm gonna--" and just wanted to get into it. And I just basically blew it off.

And then it continued. I went to class. I came out. And a whole bunch of people surrounded me, "This is the one. This is the one." And I'm just standing there like, "What?"

And then one of them said, "Yeah, he called this student a nigger" and all this. And I said, "Hold it. I didn't say any of that."

It seems at one point the whites were at a higher level than the blacks as far as social standards are concerned. Now rather than it being equal, I think-- in a black's mind, I'm speaking-- in a black's mind, the blacks are much higher than the whites. And they're band together. And they're not going to accept any whites in that band.

There's still just a lot of resentment from that '50s, '60s slavery, whatever, times. But if you look at history, how long things have been, as far as slavery, how long did that go on for, how long did it take before it ended? So how long is it going to take before blacks and whites can get along as well as blacks and blacks and whites and whites do?

Ira Glass

Well, today on our program, four attempts at answering that question. Act One, Another Politician Has God And The confederate Flag. Act Two, Nelson Mandela and Abraham Lincoln. Act Three, Good Blacks and Bad Blacks. A story by New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell. Act Four, Racial Cheerleaders. A story about somebody whose attitude about race did change. Stay with us.

Act One: A Modern Politician, His God, And The Confederate Flag

Ira Glass

Act One, a modern politician, his god, and the Confederate flag. Well, not long ago, a governor of a southern state made his own attempt at binding up the nation's wounds and achieving a lasting peace among ourselves. And frankly, it has not gone too well for him.

The governor was David Beasley of South Carolina. His state is a good place to examine how well the wounds of the Civil War are healing. It is the only state in the Union that flies the Confederate flag over its state House

Our contributing editor, Jack Hitt, is from South Carolina. And this past Thanksgiving, he watched the television address where Governor David Beasley proposed that they remove the flag from the statehouse flag pole.

Jack Hitt

The governor of the state, he's a Christian coalition candidate, one of the few who actually won high office in the elections of '94. So Beasley took control of the governor's mansion. And not long after that, a number of different things happened. Some churches were burned. There were some drive-by shootings both of blacks and of whites by people of the other race. And tensions got very, very high.

And Beasley is a good, decent man actually. One of the things that I've tried to explain to people when I've written about him is that it's a mistake to think that everybody in the Christian coalition is like Ralph Reed, i.e., a slick, media-wise, focus-group-opinionated, Washington-lobbyist insider.

Ira Glass

At one point, I remember you described Ralph Reed as being "sincerity challenged."

Jack Hitt

Yeah, right. And the irony of that is that most of the people that I know in the Christian coalition in South Carolina are, in fact, deeply sentimental about the efforts to bring equality to the races in the state and the whole civil rights effort. And in a funny way, this is going to be Beasley's downfall. Because what he did after these various shootings and other acts of violence was decide that the Christian thing to do was to take down the Confederate flag from the statehouse.

Ira Glass

In other words, it actually was a change of heart, and there was not much political advantage in it for him? He stood not to gain politically from this move?

Jack Hitt

I have asked everyone I know in South Carolina, "What would be the political advantage of a Republican bringing down the Confederate flag?" And there is none. It might be one of the few cases in American politics right now when the politician said, "I went, and I prayed. And I've decided to take down this flag," that that is, in fact, what happened.

Ira Glass

Well, good for him.

Jack Hitt

So he wins no points in his own party. It'll be so costly that I feel certain he will be thrown out of office at the next election.

Ira Glass

Because of his stand on the flag?

Jack Hitt

Because of this. Because of this, yeah.

Ira Glass

OK, so he comes on television and--

Jack Hitt

He comes on television, and what was really-- I'm sitting there with my entire family. We were all watching this. And everybody in the state is clearly watching this. It's on all the channels. It's been talked about in the papers for days.

The governor's going to address the state. And the two rebuttal arguments put forward are by other Republicans. No Democrats spoke. No black person spoke. And the other two people who spoke, Glenn McConnell, a local state assemblyman from Charleston, and Charles Condon, the Attorney General, clearly have their eyes on the Governor's chair, especially Condon.

But what was amazing about Beasley's argument for taking it down and Condon's argument for keeping it up is that they both manage to stake out rather nuanced positions about the meaning of symbols in contemporary American culture. It was strange, as I sat there listening to the Governor talking about how meaning works. And as you know, there is an entire academic discipline devoted to how we interpret signs.

Ira Glass

Right. And this is the field called semiotics, a sort of very arcane, in a certain way, academic discipline, which has swept across academia in this country in the last 15 years. Frankly, not the kind of thing which appears in our American political debate very often.

Jack Hitt

Not very often.

Ira Glass

In fact, you've written about this. I'm going to read from your writing. You say, "The speeches themselves were novel for their departure from the debate's old terms, flag is evil, flag is not evil. Rather, these speakers put forward nuanced arguments of semiotics, the science of symbols. And I don't mean they argued that the flag debate signified other issues beyond race. No, I meant that they were actually arguing semiotic theory."

Jack Hitt

Yeah, let me just read you the-- this is Beasley talking, as he's explaining why we should take the flag down. He says, this is a quote, "You see the Confederate flag flying above the statehouse flies in a vacuum. Its meaning and purpose are not defined by law. Because of this, any group can give the flag any meaning it chooses. The Klan can misuse it as a racist tool, as it has. And others can misuse it solely as a symbol for racism, as they have."

Ira Glass

And so he's basically articulating what is the central tenet of modern semiotic theory which is that you have this object, a flag, and any meaning can attach to it.

Jack Hitt

Right. But then what was amazing is that the other people who were refuting him or rebutting him basically delved into the same kind of theory. For example, here is Glenn McConnell, a state Senator from Charleston talking about the flag.

He says, quote, "We are told this flag lacks definition and must be moved to define it. But the flag was defined years ago on a monument on the statehouse grounds, which says that in the hopelessness of the hospitals, the despair of defeat, and the short, sharp agony of struggle, these South Carolinians who answered the call of their state did so in the consolation of the belief that, here at home, they would not be forgotten."

Ira Glass

In other words, the flag has a meaning, and that meaning is stable.

Jack Hitt

That meaning is stable.

Ira Glass

In other words, if the flag means honor, it's always going to mean honor. Other people can try to attach what they want, and it'll still mean that.

Jack Hitt

And it doesn't do any good. It's a very strong point of view in the South and especially in South Carolina. This is why I'm saying that I think Beasley has sort of wounded himself fatally.

Ira Glass

One of the things that I find most interesting about this in light of Lincoln's second inaugural is that the second inaugural is essentially a Christian document. It's both a political document, and it's a document arguing about faith. What are we to make of this as people who believe in God? The fact that the war happened and so many people have died. And it's interesting that Beasley would also, basically, come to this conclusion that we need to heal, the same conclusion that Lincoln comes to, as an act of faith.

Jack Hitt

Right. Well, I understand his thinking. And he came very close to pulling it off. If you appeal to the Christian sentimentality in South Carolina for good race relations, you have enormous support. Because most of these people, they don't want this antagonism, and they don't want the kind of bad feelings between the races publicly. Privately-- and this goes right to the heart of, I think, not just the South's, but America's ambiguity on race-- which is that the same heart that can get very weepy and sentimental about rebuilding black churches can also get infuriated with black leaders talking about how we need more affirmative action.

Ira Glass

So Jack, I know that you have your own modest proposal on how opponents of the Confederate flag flying over the statehouse might be able to actually get the flag off the statehouse.

Jack Hitt

Well, yes, I do.

Ira Glass

And it, in fact, is based on semiotic theory.

Jack Hitt

It is based on semiotic theory. I think the remedy would be for blacks in South Carolina to start flying the Confederate flag.

Ira Glass

Adopt the Stars and Bars as their symbol.

Jack Hitt

Adopt the Stars and Bars as the symbol of the New South. In our culture, especially, where signs and symbols can turn over so quickly, it's very easy to do what none of these guys on television were proposing, which is add even more meaning to that symbol. That's the only way you can actually alter a symbol's meaning. Even if you took the flag down, its power would remain. Its power, whether it was in a windshield or on somebody's front lawn, would still remain.

I would love to see baseball caps with Malcolm X, X is sort of rejiggered into the Stars and Bars configuration, or the Confederate flag washed with a little African liberation colors. And only blacks in South Carolina could possibly pull this off.

Ira Glass

Right. "It's our South too."

Jack Hitt

And my further prediction is is that if this did happen, if blacks did start wearing it on their T-shirts, and on their cars, and on their coats, and flying it in their front lawns or whatever, that the first group to rush to the state capital and insist that the Stars and Bars be lowered would be the Daughters of the Confederate Veterans, so enraged they would be that they symbol's true meaning was being altered.

Ira Glass

But in a certain way, looked at at the distance of a century and a quarter after Lincoln, how are we to view this entire debate?

Jack Hitt

I don't know. On the one hand, it seemed to me so many of the truly meaningful acts of integration have been accomplished. In a way, it's the kind of fight you would have after you've done all the hard work. We're really arguing, almost literally, about window dressing.

Ira Glass

But I have to say, there's another way to look at this debate. And that is that the fact that this is what's being debated about race relations and the place of blacks and whites together in society, if this is what's being debated, that means that there are all these other things which we have not solved, which are never discussed with the same fervor and political heat. You're saying the governor of South Carolina is going to lose his governorship over this symbolic question of whether to fly a flag. He is not losing his governorship over whether black children are educated as well as white children.

Jack Hitt

That's true. That's absolutely true.

Ira Glass

Jack Hitt's a magazine writer and a contributing editor here at This American Life. After he published his idea that blacks adopt the Stars and Bars, he discovered that two black entrepreneurs in South Carolina have a company called NuSouth that's trying to do exactly that. These two guys, Sherman Evans and Angel Quintero, have a full line of clothing that feature the Confederate flag rendered in the colors of African liberation, red, black, and green. They have a store on Main Street in downtown Charleston. They hope to expand to all 13 original colonies.

Representative Of Nusouth

Realistically, we all know that the Confederate flag is the negative enemy. And the creation of a New South flag is kind of an act that don't move. We figured it's like the oppressor's worst insult, where we take that, and we wear it with pride. It's kind of like a strategy whereby you go right into the feared thing, and you claim it.

Ira Glass

Do they have a website? Well, of course. www.nusouth-- spelled N-U-S-O-U-T-H-- dot. com.

Act Two: Nelson Mandela And Abraham Lincoln

Ira Glass

Act Two, Nelson Mandela and Abraham Lincoln. What to do with the symbols of a white supremacist past? Well, after the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln did not ban the Confederacy's national anthem "Dixie." Instead, he had it played on the White House lawn, saying, in effect, we're all one nation, this song is all of ours. It's a strategy, I think, Nelson Mandela would understand.

In fact, that story about Lincoln and Jack Hitt's story about South Carolina reminded me of a story that I had been told by a friend of mine named John Matisonn. John is from South Africa. During apartheid, he was the chief political correspondent at the leading opposition newspaper, The Rand Daily Mail. For a while, he was National Public Radio's correspondent in South Africa, which is how I know him. When Nelson Mandela was released from prison, John was the reporter given the honor of asking Mandela the first question at his very first press conference. Now he's a member of Mandela's government.

And a few years ago, he told me about the Springboks. The Springboks are a rugby team. Under apartheid, rugby was the favorite game of South African whites. Now for blacks, the favorite game, the national game, was soccer. But for whites, it was rugby.

And the Springboks were the national team, the team that would go to the international competitions, things like that. And it was all white or almost all white, with one or two black players. The Springboks were seen as a symbol of white South Africa and apartheid. When Nelson Mandela's party, the African National Congress, came to power, there was this big debate over whether to get rid of the team's name and its logo. A springbok is like-- it's like a deer. And just like the flag debate in South Carolina, John Matisonn says, the debate got very emotional.

John Matisonn

And I would have to say that most people in the ANC camp would have argued strongly that the Springbok cannot be retained. It's too toxic a symbol. It had to be removed and replaced with something else. And there was even discussion about alternatives. And the plan was that a decision was going to be taken after the World Cup.

Ira Glass

During apartheid, international sanctions had kept South Africa out of the World Cup. And so at the first World Cup game of the post-apartheid era, a game hosted by South Africa, Nelson Mandela settled this issue of the springbok symbol once and for all.

John Matisonn

Mandela walked out onto the field wearing a Springbok jersey with the number six, which was the same number as the captain. And he walked out into the middle of the field, and he just wished them well and cheered. And the crowd just roared. And he wore a Springbok cap as well.

And then at the end of the game, South Africa won. And he walked out onto the field, and he hugged the captain of the winning team. And so you had jersey number six hugging jersey number six, the captain of the rugby team and the captain of South Africa.

Ira Glass

If I remember right, back when it happened, you told me that grown men were crying in the stands.

John Matisonn

Oh yeah. It was very emotional. People had tears in their eyes. And I think it had an amazing impact because black South Africans just adored it. They adored him. And white South Africans as well.

They adored the fact that he'd embraced all their symbols, and hadn't rejected them, and made a big fight about it, and turned it into something that could have, potentially at least, at a symbolic level, been ugly. And at the same time, black South Africans said-- it had the effect of people saying, "Well, it's ours. It's not their team anymore. It's our team."

And I think I told you the story that I was at a Christmas party-- our own Christmas party-- and nearly all our staff are black South Africans. And half the black South Africans wore Springbok caps to the Christmas party, which if you're sort of seeped in local political folklore, as I am, it was just an amazing and very moving sight. And frankly, now it's just not an issue. It really isn't.

Ira Glass

Nelson Mandela has systematically tried to diffuse the old symbols of apartheid, all of them, of their power. He traveled to formerly all-white neighborhoods. He made the old apartheid national anthem part of the new national anthem. At one point, Nelson Mandela held a lunch, and he invited the wives and the widows of all the prime ministers from during the apartheid era. And he also invited the wives and widows of all the black leaders from that era as well, including Steve Biko's widow.

John Matisonn

And of course, you know that Steve Biko was killed in prison by policemen in support of the old government. And that was in the time under the premiership of John Vorster. And Mrs. Vorster was there. John Vorster died some time ago. But Mrs. Vorster was there.

And there was this remarkable scene, which was shown on television and reported in the newspapers, where they're all in the garden, sitting with these garden chairs. And Mrs. Vorster sees Mrs. Biko looking for a place to sit. And she sort of jumps up and offers her her seat. And as you know, John Vorster was really regarded as one of the worst authoritarian leaders. He was minister of police at the same time he was prime minister.

And Mandela went up to her, and he brought a chair. And she said, "No, no, no, let me give her my chair." And Mandela looked at her very sternly and wagged his finger at her and said, "Now Mrs. Vorster, you must sit down and do as I say. Otherwise, I'm going to be as authoritarian as your husband was." And everybody laughed quite uncomfortably, not quite sure what to make of it.

But of course, the next thing, Mrs. Vorster did as she was told by the president. And she sat down. And Mrs. Biko sat down in the chair that Mandela brought for her. And they got into conversation.

Ira Glass

This actually leads to the thing I was going to ask you next, which was how important do you think these symbolic changes are in changing a nation? How important are they versus, say, building houses and getting the economy working in a different way?

John Matisonn

Well, I must say, I, as a sort of a hard-bitten political journalist all my life, probably didn't take them as seriously as the government did. I looked at housing statistics, and educational changes, and budgets, and all those kind of things. But I have to concede, I was wrong. I failed to appreciate the importance of these symbols. They've been extremely important.

I still meet black South African friends who surprise me by telling me about perhaps their less political family members who went, after these symbolic changes, went to parts of white Cape Town and white Johannesburg that they'd never been before. And frankly, they could have gone before because they were not actually legally prohibited for some time before that, but they'd never felt comfortable doing. And so the symbolic change meant, suddenly, people felt symbolically they could go to areas where they might have been legally entitled to for some years, but they wouldn't go there at that time because they still felt uncomfortable. That's, I think, the success.

And if you are to ask me, "What has changed for the average black South African since the election?" In terms of housing and so on, the improvements are modest. The vast mass of black South Africans, their material conditions haven't improved radically. And, in many cases, not at all, one has to admit. But what has really changed, and it is a genuine change for people, is psychological liberation, a feeling that this is their country, and that they have opportunities and possibilities in the country, and that the country is theirs. I have to say, I think that has real meaning.

Ira Glass

John Matisonn in South Africa. Coming up, Good Blacks and Bad Blacks, Good Whites and Bad Whites. That's all in a minute when our program continues.

Act Three: Good Blacks, Bad Blacks

Ira Glass

From WBEZ Chicago and Public Radio International, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a theme, invite a variety of writers, and performers, and reporters to tackle that theme with original documentaries, radio monologues, found tape, anything they can think of. Today's show for the Fourth of July weekend, how we're doing, as a nation, healing the wounds of our nation's original sin of slavery.

We're at Act Three, Good Blacks, Bad Blacks. For a perspective on how far black America and white America have come in integrating into one America, consider this story from New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell about his cousins who emigrated to this country from Jamaica 12 years ago, scrimped and saved to make a life here.

Malcolm Gladwell

My cousin Rosie and her husband Noel live in a two-bedroom bungalow on Argyle Avenue in Uniondale, in a working-class neighborhood on the west end of Long Island. From the outside, their home looks fairly plain. But there's a beautiful park down the street, the public schools are supposed to be good, and Rosie and Noel have built a new garage and renovated the basement.

Now that Noel has started his own business as an environmental engineer, he has his own office down there. Suite 2B, it says on his stationery. And every morning, he puts on his suit and goes down the stairs to make calls and work on the computer. If Noel's business takes off, Rosie says, she'd like to move to a bigger house in Garden City, which is one town over. She says this even though Garden City is mostly white.

In fact, when she told one of her girlfriends, a black American, about this idea, her friend said that she was crazy, that Garden City was no place for a black person. But that's just the point. Rosie and Noel are from Jamaica. They don't consider themselves black at all.

This doesn't mean that my cousins haven't sometimes been lumped together with American blacks. Noel had a job once removing asbestos at Kennedy Airport. And his boss called him a nigger and cut his hours. But Noel didn't take it personally. "That boss," he says, "didn't like women or Jews either, or people with college degrees, or even himself, for that matter."

Another time, Noel found out that a white guy working next to him in the same job and with the same qualifications was making $10,000 a year more than he was. He quit the next day. Noel knows that racism is out there. It's just that he doesn't quite understand or accept the categories on which it depends. The facts of his genealogy, of his nationality, of his status as an immigrant made him, in his own eyes, different.

This question of who West Indians are and how they define themselves may seem trivial, like racial hairsplitting, but it's not trivial. In the past 20 years, the number of West Indians in America has exploded. There are now half a million in the New York area alone. And despite their recent arrival, they make substantially more money than American blacks. They live in better neighborhoods. Their families are stronger.

In the New York area, in fact, West Indians fare about as well as Chinese and Korean immigrants. What does it say about the nature of racism that another group of blacks, who have the same legacy of slavery as their American counterparts and are physically indistinguishable from them as well, can come here and succeed as well as the Chinese and the Koreans do? Is overcoming racism as simple as doing what Noel does, which is to dismiss it, to hold himself above it, to brave it and move on? Why is one group of blacks flourishing when the other is not?

The implication of West Indian success is that racism doesn't really exist at all, at least, not in the form that we've assumed it does. It implies that when the conservatives in Congress say that the responsibility for ending urban poverty lies not with collective action, but with the poor themselves, that they're right. I think of this sometimes when I go with Rosie and Noel to their church, which is in Hempstead, just about a mile away. It was once a white church, but in the past decade or so, it's been taken over by immigrants from the Caribbean. They've so swelled its membership that the church has bought much of the surrounding property, and it's about to add 100 seats or so to its sanctuary.

The pastor, though, is white. And when the band up front is playing and the congregation is in full West Indian form, the pastor sometimes seems out of place, as if he cannot move in time with the music. I always wonder how long the white minister at Rosie and Noel's church will last, whether there won't be some kind of groundswell among the congregation to replace him with one of their own. But Noel tells me the issue has never really come up.

Noel says, in fact, that he's happier with a white minister for the same reason that he's happy with his neighborhood, where the people across the way are Polish, and another neighbor is Hispanic, and still another is a black American. He doesn't want to be shut off from everybody else, isolated within the narrow confines of his race. He wants to be part of the world. And when he says these things, it's awfully tempting to credit that attitude with what he and Rosie have accomplished. Is this confidence, this optimism, this equanimity all that separates the poorest of American blacks from a house on Argyle Avenue?

This idea of the West Indian as a kind of superior black is not a new one. When the first wave of Caribbean immigrants came to New York and Boston in the early 1900s, other blacks dubbed them "Jew-maicans" in derisive reference to the emphasis they placed on hard work and education. In the 1980s, the economist Thomas Sowell gave the idea serious intellectual imprimatur by arguing that the West Indian advantage was a historical legacy of Caribbean slave culture. According to Sowell, in the American South, slave owners tended to hire managers who were married in order to limit the problems created by sexual relations between overseers and slave women.

But the West Indies were a hardship post without a large and settled white population. There, the overseers tended to be bachelors. And with white women scarce, there was far more co-mingling of the races. The resulting large group of coloreds soon formed a kind of proto middle class, performing various kinds of skilled and sophisticated tasks that there were not enough whites around to do, as there were in the American South. They were carpenters, masons, plumbers, and small business men many years in advance of their American counterparts, developing skills that required education and initiative.

My mother and Rosie's mother came from this colored class. Their parents were schoolteachers in a tiny village buried in the hills of central Jamaica. My grandmother and grandfather's salaries combined put them, at best, on the lower rungs of the middle class. But their expectations went well beyond that. My mother and her sister were pushed to win scholarships to a proper English-style boarding school on the other end of the island. And later, when my mother graduated, it was taken for granted that she would attend university in England.

My grandparents had ambitions for their children. But it was a special kind of ambition, borne of a certainty that American blacks did not have, that their values were the same as those of society as a whole and that hard work and talent could actually be rewarded. This, I think, is why Noel cannot quite appreciate what it is that weighs black Americans down. He came of age in a country where he belonged to the majority.

It is tempting to use the West Indian story as evidence that discrimination doesn't really exist, as proof that the only thing inner-city African-Americans have to do to be welcomed as warmly as West Indians is to make the necessary cultural adjustments. But, in fact, studies of workplaces that hire West Indians show they are not places where traditional racism has been discarded. They're actually places where old-style racism and appreciation of immigrant values are somehow bound up together. Listen to a white manager who was interviewed by the Harvard sociologist Mary Waters.

"Island blacks who come over, they're immigrant. They may not have had such a good life where they are, so they're going to try to strive to better themselves. And I think there's a lot of American blacks out there who feel we owe them. And enough is enough already. You know? This is something that happened to their ancestors, not now. I mean, we've done so much for the black people in America now, it's time that they got off their butts."

Here then are the two competing ideas about racism side by side. The manager issues a blanket condemnation of American blacks even as he holds West Indians up to a cultural ideal. The example of West Indians as good blacks makes the old blanket prejudice against American blacks all the easier to express. The manager can tell black Americans to "get off their butts" without fear of sounding, in his own ears, like a racist because he has simultaneously celebrated island blacks for their work ethic.

The success of West Indians is not proof that discrimination against American blacks does not exist. Rather, it's the means by which discrimination against American blacks is given one last vicious twist, as if to say, "I'm not so shallow as to despise you for the color of your skin because I've found people your color that I like. Now I can despise you for who you are."

I grew up in Canada, in a little farming town an hour and a half outside Toronto. My father teaches mathematics at a nearby university. My mother's a therapist. For many years, she was the only black in town. But I can't remember wondering, or worrying, or even thinking about this fact.

Back then, color meant only good things. It meant my cousins in Jamaica. It meant the graduate students from Africa and India my father would bring home from the university. My own color was not something I ever thought about much either because it seemed such a stray fact.

But things changed when I left for Toronto to attend college. This was during the early 1980s, when West Indians were emigrating to Canada in droves, and Toronto had become second only to New York as the Jamaican expatriates' capital in North America. At school, in the dining hall, I was served by Jamaicans. The infamous Jane Finch projects in northern Toronto were considered the Jamaican projects. The drug trade then taking off was said to be the Jamaican drug trade. In the popular imagination, Jamaicans were, and are, welfare queens, and gun-toting gangsters, and dissolute youths.

After I had moved to the United States, I puzzled over this seeming contradiction, how West Indians celebrated in New York for their industry and drive could represent, just 500 miles northwest, crime and dissipation. Didn't Torontonians see what was special and different in West Indian culture? But that was a naive question. The West Indians were the first significant brush with blackness that smug, white Torontonians had ever had. They had no bad blacks to contrast with the newcomers, no African-Americans to serve as a safety valve for their prejudices, no way to perform America's crude racial triage.

There must be people in Toronto just like Rosie and Noel with the same attitudes and aspirations, who want to live in a neighborhood as nice as Argyle Avenue, who want to build a new garage, and renovate their basement, and set up their own business downstairs. But it's not completely up to them, is it? What has happened to Jamaicans in Toronto is proof that what's happened to Jamaicans here is not the end of racism, or even the beginning of the end of racism, but an accident of history and geography. In America, there is someone else to despise. In Canada, there is not. In the new racism, as in the old, somebody always has to be the nigger.

Ira Glass

Malcolm Gladwell's story first appeared in the New Yorker magazine.

Act Four: Good Whites, Bad Whites

Ira Glass

Act Four, Good Whites, Bad Whites. This next assessment of our state of national racial healing, from radio producer Cecilia Vaisman and Christina Egloff with Jay Allison, about a woman named Carolyn Wren Shannon and her neighbors.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

My mother was telling us that one time, when we were younger, my father was very prejudiced. And I come home from school with this friend. And he was on the recliner with a newspaper. And I said, "Mum, can my friend stay over for supper?" And my father dropped the paper to look to see who it was, and it was a little black girl. She said, my father almost swallowed his false teeth.

And she was like, "Honey, I don't really think that's a good idea." She said, I come in, and my father was horrified. Because I really didn't see things-- I don't know. I was colorblind really until that incident. And then we kind of got the rules that that wasn't accepted.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Who you calling?

Cheerleader Captain

Ready?

Cheerleaders

[CHEERING] Go. F-I-G-H-T, fight, fight. F-I-G-H-T, fight, fight.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

My mother and father are both from Charlestown. All of my great-grandparents are from Ireland. All four of them. And that's how the majority of this community works.

Most of them, when they come over on the boat, they all were together and settled together. And that's how this community has stayed the same. You'll find that a lot of the people in this community are related because I think there's some security having family around. And people are proud that their Irish, and they're proud that they're Catholic.

And I think people-- they stick to their own. When we were in grammar school, there was one teen who was Protestant. And we goofed on him because he didn't believe in the same thing as us. Course, no one understood what a Protestant was, just that he was different.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Are you ready, girls? [MAKES A HUMMING SOUND, SETTING THE PITCH] Go ahead. Go. Follow her lead.

Ladies

[SINGING] We are the girls from Charlestown you hear so much about. Most everybody looks at us whenever we go out. We're noted for our reputation and the things we do. But what the hell do we care? The boys are naughty too.

One Of The Ladies

Wasn't that fun?

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Drink with the straws. You know the little--

We are here at my Aunt Mary Ellen's house on Elm Street in Charlestown. I'm here with my Aunt Linda, my cousin Patty, my cousin Donna, my sister-in-law Mimi, my cousin Mary Ann, my Aunt Barbara, my cousin Sheila, and my Aunt Mary Ellen. My grandmother, who is the matriarch of this wonderful family. Mary Wren, wonderful woman, she had seven children. And she had 32 grandchildren and 43 great-grandchildren. I'd say about 70% are still local.

Carolyn's Relative 1

Most people don't understand it if they're from the town. There's always that Charlestown-- they want to be, they wish they were, they don't understand what it's like.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

There's strength in numbers. And that's what happens here. Everybody knows everybody. So it's a kind of strength that you don't find in other areas. To have 17,000 people and the majority of them have major relatives around, it makes a big difference in this community.

Carolyn's Relative 2

Charlestown is home.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Yeah.

Once busing occurred, that wonderful year of '76, 1976, when the federal government mandated busing, court-ordered busing, my junior year was totally insane. Everything changed. There were new faces. People were never exposed to minorities. And all of a sudden, you're thrown in a classroom.

And there's turmoil on the streets, and there's turmoil in your house, and there's turmoil on the news. And the city's erupted with racial violence. And everyone's following everyone. Whatever the crowd does. If they throw rocks, you throw rocks. If they beat up a black person, then you stand and watch.

Whereas, as a Catholic, you realize that you don't treat someone like that. But everyone forgot everything. It was like this total mayhem.

School wasn't the same. There were metal detectors put in the classroom, in the entrance of the schools. There were policemen everywhere. At night, they would burn cars. It was total crazy.

There was a major rally on Boston, City Hall Plaza. And a black man was attacked with an American flag because he was black and walked in front of their rally, which was all white. They speared him with the American flag. It was a horrible, horrible scene.

It was all over the news across the world. Charlestown, Southie, they're racist. Boston is a place full of hate. And it was. It was.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Just start it.

Cheerleaders

[CHEERING] [UNINTELLIGIBLE] is the team that we're gonna defeat, so come on, everybody, do the Townie beat.

Cheerleader Captain

Once, guys, come on. Let's go.

Cheerleaders

[CHEERING] One, two, three, four, clap, one, two, clap, one, two, three, four, five, six, clap, one, two, clap, one, two, clap, clap.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

When I was in junior high, the biggest thing was to get up to the high school because that was where your mother went and your father went. And those teachers were still there. And you could still talk to your mother about the bathroom story. But that doesn't occur anymore because there is no Charlestown High like it used to be. And now the school itself is predominately black.

My kids will probably go to parochial schools. They won't do Charlestown High cheers. They may do St. Clement's cheers.

But when my aunts get together, they all sing Charlestown High songs. And it's like a little pep rally when we're all at a family gathering. But that won't happen for my kids. And I think that's kind of sad.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Put your hands on your hips, and we'll do it regular. OK, put 'em up. Close your feet. Say, ready.

Little Girl

[CHEERING] Go. Townie team means victory any way you spell it.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Hey, very good, girls.

Jay Allison

What does Townie team mean?

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Townie Teenie. You gonna go to cheerleading today? Huh? We're gonna go down to cheerleading?

What happened on the Oprah show was she had on a white man who was married to a white woman. He disowned his children for being associated with black men. And then he, in fact, disowned his grandchildren because they were black in them. And I was saying, "That's a disgrace. That's your blood. You don't disown anyone." And Danny said--

Danny

I don't know. What did I say?

Carolyn Wren Shannon

You said that you thought he was right.

Danny

I said I don't know what I would do. But I understood his feelings. So you wouldn't mind your daughters marrying a black guy?

Carolyn Wren Shannon

I didn't say that, which we have discussed at great length. That is definitely a fear of mine, that I would like to think I'm open minded about race, more so than I've ever been. But if it came down to my daughters choosing another race, I don't think I'd be happy with that.

Danny

I wouldn't say I'm racist, but I definitely have bitter feelings towards blacks. I was raised that way too. My father's an Archie Bunker. I think it rubs off on you.

I would never say anything to my girls. But they'll learn. They'll learn what's theirs, what's your own, and things like that just growing up around the same type of people. They'll look at anyone that's not like them differently. I don't have to tell them that.

It sounds ignorant, but I had no pro-- I like the way I grew up. Carolyn's of the same mold. And I don't have a problem with that. I'm not gonna push it on 'em at all.

But I hope someday they marry an Irish-Catholic boy. I don't think there's anything wrong with that. Other people say, that's being racial. I think it's natural to like your own kind of people.

You sing too, Bridget. Help her out.

Little Girl

[SINGING] I love you. You love me. We're a happy family. With a great big hug and a kiss from me to you. Won't you say you love me too?

Danny

I think it's a real breed of person. You must have to grow up somewhere where you walk down the street, and there's a black kid, a Chinese kid, a white kid, and a Puerto Rican kid playing together. I just can't even imagine that. That's some kind of a made-up fairy tale, I think, where everyone gets along together. I can't imagine it.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Life teaches you sometimes very painfully. And I think that's your best teacher anyway. No one can tell you not to be racist, and they can't tell you to like your black neighbor. You have to learn. So I think it's a person's choice. So you can choose to be ignorant, or you can choose to be fair.

I was captain of the cheerleaders. And I remember Miss Kessner, which was the cheerleading coach, was also the phys ed director. And she said, she hadn't chose the captains yet. And this was something that I wanted my whole life. This was my big goal in life to be cheerleading captain.

And she said to me one day, "If a black girl tries out for cheerleading, will you accept her?" And I thought to myself, "I'm gonna be a jerk if I don't go along with the crowd." It was a very difficult decision for me. And I knew this could jeopardize whether I'd become captain or not. And I said, "I wouldn't accept her." She put her head down, and she walked away.

So the day of cheerleading tryouts, she come into the room of all the girls, and she said, "Traditionally, Charlestown High has had two cheerleading captains. This year, they'll only be one." And I put my head down, and I started to cry because I knew I blew it. It was my first experience with race and making the wrong decision.

So we're all in the room, and she says, "The cheerleading captain for this year is Carolyn Wren." I started bawling my eyes out. And I was like, "Oh, my god." And I looked up at her. And she knew that I knew that I had made a wrong choice. I knew I made the wrong choice, but I made it from my heart because I was raised in a house where race wasn't accepted.

Woman 1

That's crazy. That's embarrassing. I think they're embarrassing, the Charlestown High cheerleaders.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

What's wrong with them?

Woman 1

Because they don't cheer like your regular cheerleaders anyway. They cheer like jigaboos or something. I don't know. Carol, that is not cheering. It's boge. They're like clapping, and singing, and getting down with their cheers. It's not even--

Woman 2

It's jive cheerleading.

Woman 1

It's jive cheering. Yeah.

Woman 2

It's not your good old cheerleader cheering.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

It's not what they teach you at cheerleading camp. The all-American cheerleader. It's not that style. It's more ethnic. It's more cultural. It's very different than what we're used to.

Woman 2

Definitely.

Woman 1

See, my sisters wouldn't cheer for Charlestown High because of it. I can't even think of a cheer that we could compare it to other than "How funky is your chicken."

Carolyn Wren Shannon

No, they do that "We don't need no music to cheer." And they stamp their feet. And they do like this little dance.

Woman 1

And they do like [CLAPS AND STAMPS]. Oh, you want to just slap them and say, "Stop, you look so foolish."

Carolyn Wren Shannon

But that's all they know. That's what they're taught. And that's what they're excited to do.

Woman 1

Nobody's excited to have 'em. Everybody just wished they'd go away.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

I remember sitting beside a girl in school. And she had an Afro. And we had common pins in health. Not health. Sewing. It was home ec.

And we used to put paper at the end of the common pin and toss the common pin. And the paper would allow it to weigh it down, so you could send it. And we would put them into her hair. And this was hitting her head.

We tortured that girl because she was different and because she had an Afro, and none of us did. Because she was black. And I was a part of that. I was as racist as the next one. It's not something I'm proud of.

And I think working with teenagers, it's a constant effort to remind them that you don't judge someone by the color of their skin.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

OK, tonight's conference is gonna be on racism. We realize it's a very sensitive issue. We're not here to try to change anybody's mind. All we want to do is raise your consciousness about it. Want to talk about it. Want to have a lot of fun with it. Couple of rules. Watch your mouth. No swearing. A little respect. You can, of course, speak your own opinions, but with a little taste. Understand? OK, we're gonna start.

If you asked me when I was 10, would I be working for the city with other black people, I would've told you, you were crazy, that I'm above them, that I don't work with niggers. That's what I woulda told you when I was 10.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Yeah, when I first took this job, I actually had trouble working with people across the city because I was really racist. But I was in the high school when there was busing. So there was a lot of racial riots. There was total mayhem every day. I hated them. It was just those things and their Afros.

[LAUGHTER]

I hated them. I didn't want to look at them. I didn't want to talk to them. I was the class vice president and almost lost the post because I wouldn't accept black students in Charlestown High.

I've taken incredible strides as far as accepting. I've matured. I'm educated. It's very different than when I was 17, and filled with a lot of hate, and was surrounded by a lot of people who hated because of the color of their skin.

Carolyn Wren Shannon

OK, this warm-up-- guys, you need to listen-- this warm-up is called motion circle. So what I want you to do is walk-- spread out a little more-- and I want you to walk. Come this way. Just walk in a circle. OK, now I'm going to tell you do something. I want you to all of a sudden do it, OK? Walk like you're stuck in quicksand.

Young Person

Stuck in what?

Carolyn Wren Shannon

Stuck in quicksand. Walk like you're Irish.

[LAUGHTER]

OK. Keep walking. Walk as if you're carrying something heavy. OK, walk like you're black.

[LAUGHTER]

My father, who used to be incredibly racist and has grown out of that-- I can't even believe it. He's just not the same person. And he accepts people for what they are, which was very important for all of us to see. Because you lead by example. And if you can't lead by example-- it's such an important part of, I think, each family.

And I would say, on a whole, that the majority of racism is learned in the home. It's what you're brought up with. It's what you hear. It's what you're told. And it's how you're raised.

And if you go out and you think that battering someone because they're black, then I would bet my paycheck that, in your home, racism is a serious issue and also a serious problem. And it was for me. And it's taken me a long, long time to overcome it. Although I still have fears. Although I'm open minded and educated, I still have some of those fears.

Ira Glass

That story was first produced in a slightly longer form for WGBH in Jay Allison's Life Stories series. Engineering by Jane Pipik. Cecilia Vaisman did the original interviews.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Elise Spiegel and myself with Nancy Updike and Julie Snyder. Musical help from Sarah Vowell. Contributing editors Sarah Vowell, Jack Hitt, Margy Rochlin, and Paul Tough. To buy a cassette of this program, call us at WBEZ in Chicago, 312-832-3380. That's 312-832-3380. Our email address, [email protected].

[FUNDING CREDITS]

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. WBEZ management oversight by Torey Malatia, who makes most of his management decisions this way.

Jack Hitt

I went, and I prayed.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.