81: Guns

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

Dear friend, it's true. If there's even the slightest possibility that you'll have to use your gun someday for self-defense, this is going to be the most important letter you've ever read. I'm not kidding. So please do yourself a favor. Go to someplace quiet, close the door, and tell everyone not to disturb you for the next 5 or 10 minutes. Done? Good. I'm only asking that you do this because I want you to carefully absorb and consider what I'm about to share with you. It really could save your life someday.

Well, this is an open letter from this issue of American Handgunner magazine. It's actually written by Ben Cooley, who's described as somebody with 13 years of experience in counterterrorism, hostage rescue, and SWAT training. It is a four-page single-spaced letter with lots of things underlined and bolded everywhere. It's actually a full-page ad. His thesis basically is that you have to have the fighting mindset. Naturally you have to have a gun, but in addition to a gun, more important than the gun, is what is going on in your head. Let me just read you a little bit here.

Hollywood will get you killed. Tragically, almost everyone alive today learns their so-called fighting skills from what they see on TV and in the movies. I say "tragically" because everything you see on TV and film is absolutely the opposite of what you should do in a real life armed confrontation. Yes, I know it's almost heresy to say it, but even Dirty Harry would get his head blown off if he tried these stunts in real life.

I've been reading gun magazines, and more than anything I've read in any of the issues of any of the gun magazines, this ad completely gets to me, and I've been trying to think about why. And I think the reasons are these. Number one, its central attitude, its central thesis is everything you know is wrong. Number two, it says Hollywood is trouble. Number three, it tells you that gadgets and fancy stuff cannot help you. What will help you, the only thing that can help you, is the right attitude. Number four, it says that all I need to do is buy a video for $97, and a gun, of course, but mainly video, and I'm set.

I read this and I have to say I want more. I want this. Which is not an easy thing to achieve with an ad, because the gap between gun owners and people who don't own guns, like myself, that is a vast gap in our country. It's two different cultures. But this ad, I don't know what. It's a thing about it's everything you know is wrong, can-do badassery. I get this ad. This ad bridges the gap.

And that is also the mission of today's radio program. From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Today on our program, we try to bridge the gap between Americans who love their guns and Americans who hate them.

Act One of our program, the NRA meets NEA. Our own Sarah Vowell goes out shooting with her dad and a gun that weighs 110 pounds.

Act Two, Fists and Guns. A gun control advocate, Geoffrey Canada, explains the pleasure and power of carrying a gun.

Act Three, Shooter, how somebody goes from victim to perp in one day.

Act Four, Potato Potahto, what it's like getting shot at. We hear from two people who drew completely opposite conclusions from the experience.

Act Five, Straw Man. We'll talk with a man who has put five dozen illegal guns into the hands of criminals for less money than you made this year. Stay with us.

Act One: Nra Vs Nea

Ira Glass

Act One, NRA versus NEA. Sarah Vowell says that growing up in Oklahoma and Montana, she did not agree with her father about guns. And then one day, back when she was mostly a music critic writing for Spin and all sorts of places like that, she tried to cross the cultural chasm that divides the gun haters from the gun lovers in this country.

Sarah Vowell

If you were passing by the house where I grew up during my teenage years, and it happened to be before election day, you wouldn't have even needed to come inside to see that it was a house divided. You could just look at the Democratic campaign poster in the upstairs window and the Republican one in the downstairs window, and see our home for the civil war battleground it was. I'm not saying who was the Democrat and who was the Republican, my father or I, but I will tell you that I am not the one who plastered the family truck with National Rifle Association stickers, that I have never subscribed to Guns & Ammo, and that hunter's orange was never my color. About the only thing my father and I agree on is the Constitution, though I'm partial to the First Amendment while he's always favored the Second.

I am a gunsmith's daughter. In our house, or as I like to call it, the United States of Firearms, guns were everywhere-- the so-called pretty ones hanging on the wall, Dad's clients' fixer-uppers leaning in the corners, an entire rack right next to the TV. I had to move revolvers out of my way to make room for my bowl of Rice Krispies on the kitchen table.

Now I even giggle when Dad calls me on election day to cheerfully inform me that he has once again canceled out my vote, but I was not always so mature. There were times when I found the fact that he was a gunsmith horrifying and just weird. All he ever cared about was guns. All I ever cared about was art. And there were years and years when I holed up in my room reading Allen Ginsberg poems, and he hid out in the garage making rifle barrels, and we weren't capable of having a conversation that didn't end up in argument.

I have only shot a gun once, and once was plenty. My twin sister Amy and I were six years old-- six-- when Dad decided it was high time that we should know how to shoot. Amy remembers the day he handed us the gun for the first time differently. She liked it. She says that she thought it meant that Daddy trusted us, and that he thought of us as big girls.

But I remember holding the pistol only made me feel small. It was so heavy in my hand. I stretched out my arm and pointed it away and winced. It was a very long time before I had the nerve to pull the trigger, and I was so scared I had to close my eyes. It felt like it just went off by itself, as if I had no say in the matter, as if the gun just had this need. The sound it made was as big as God. It kicked little me back to the ground like a bully, like a foe. It hurt. I don't know if I dropped it or just handed it back over to my dad, but I do remember that I never wanted to touch another one again. And, since I believed in the devil, I did what my mother told me to do every time I felt an evil presence. I whispered under my breath, Satan, I rebuke thee.

Now it's not like I'm saying I was traumatized. It was more like I was decided-- guns, not for me. Lucky for me, both my parents grew up in exasperating households where children were considered puppets and/or slaves. So my mom and dad were hell-bent on letting my sister and me make our own choices. So if I decided that I didn't want my father's little death sticks to kick me to the ground again, that was fine with him. He'd go hunting with my sister, who started calling herself the loneliest twin in history because of my reluctance to engage in family activities.

Of course, the fact that I was allowed to voice my opinions did not mean that my father would silence his own. Some things were said during the Reagan administration that cannot be taken back. I won't bore you with the details. Let's just say that I blamed my father for nuclear proliferation and Contra aid, while he believed that if I had my way, all the guns would be confiscated, and it would take the commies about 15 minutes to parachute in and assume control.

We're older now, my dad and I, and the older I get, the more I'm interested in becoming a better daughter. First on my list, figure out that whole gun thing.

Not long ago, my dad finished his most elaborate tool of death yet, a cannon. He built a 19th century cannon from scratch. It took two years. After tooling a million guns, after inventing and building a rifle barrel boring machine, after setting up a complicated shop filled with lathes and bluing tanks and outmoded blacksmithing tools, the cannon is his most ambitious project ever. I thought that if I was ever going to understand the ballistic bee in his bonnet, this was my chance. It was the biggest gun he ever made, and I could experience it and spend time with it with the added bonus of not having to actually pull a trigger myself.

I called Dad and said that I wanted to come watch him shoot off the cannon. He was immediately suspicious. He seemed nervous when I told him I wanted to record it, but I had never taken an interest in his work before, and he would take what he could get.

I flew home to Montana. He loaded it into the back of his truck, and we drove up into the Bridger Mountains.

Sarah Vowell

And the National Forest Service doesn't mind you setting off fiery balls of metal onto their property?

Pat Vowell

You cannot shoot fireworks, but this is considered a firearm.

Sarah Vowell

So that's OK?

Pat Vowell

[INAUDIBLE].

Sarah Vowell

I should mention that it is a small cannon. It's as long as a baseball bat and as wide as a coffee can, so it's heavy. 110 pounds. We get to the mountain. My dad takes his gunpowder and other toys out of this adorable wooden box on which he has stenciled Pat G. Vowell Cannonworks. He plunges his homemade bullets into the barrel, points it at an embankment just to be safe, and lights the fuse.

Sarah Vowell

The fuse is lit. This is like a cartoon.

[CANNON FIRES]

Oh my god. Oh, there's smoke everywhere. It's like the Fourth of July. [SINGS] Oh beautiful, for spacious skies--

I've given this a lot of thought, how to convey the giddiness I felt as the cannon shot off, and I wish there were a more articulate way to say this, but I'm telling you, there isn't. It's just really, really cool. My dad thought so too. It's also loud, louder than I can possibly convey over the radio. No, let me amend that. If you want to understand how loud it was, in a moment, not yet, but when I say, turn the volume on your radio all the way up. Ready? Now.

[CANNON FIRES]

Sarah Vowell

God.

It was so loud and so painful, I had to touch my head to make sure my skull hadn't cracked open. Here's something my dad and I share. We're both a little hard of hearing. Me from Aerosmith, him from gunsmith. Hey, turn it up again.

[CANNON FIRES]

Sarah Vowell

Man, good shot Dad.

Just as I was wondering what was coming over me, two hikers walked by. We forced them to politely laugh at our jokes for a while, and Dad set the cannon off again so they could see how it works.

Hiker

So you work for the radio, and that's your dad?

Sarah Vowell

Yeah.

Hiker

That's neat.

Sarah Vowell

Then this odd thing happens. When one of the hikers says, that's quite the machine you got there, he isn't talking about the cannon. He's talking about my tape recorder and my long radio microphone. I stare back at him, then I look over at my father's cannon, and down at my microphone, and I think, oh my god, my dad and I are the same person. We're both smart-alecky loners with goofy projects and weird equipment. And since this whole target practice outing was my idea, I was no longer his adversary. I was his accomplice. And what's worse, I was liking it.

I haven't changed my mind about guns. I can get behind the cannon because it is a completely ceremonial object. It's unwieldy and impractical just like everything else I care about in the world. Try to rob a convenience store with this 110-pound Saturday night special, you'll still be dragging it in the door Sunday afternoon.

[CANNON FIRES]

I love noise. I make my living writing about it, and I'm always waiting for that moment in a song when something just flies out of it and explodes in the air. My dad is a one-man garage band, the kind of rock-and-roller who slaves away at his art for no other reason than to make his own sound. My dad's an artist, a pretty driven idiosyncratic one too, and he's got his last Gesamtkunstwerk all planned out. It's a performance piece. We're all in it, my mom, the loneliest twin in history, and me.

Here's how it goes. When my father dies, take a wild guess what he wants done with his ashes. Here's a hint. It requires a cannon.

Pat Vowell

You guys are going to love this. You get to drag this thing up on top of the Gravellies on opening day of hunting season, and looking off at Sphinx Mountain, you get to put me in little paper bags, and I can take my last hunting trip on opening morning.

Sarah Vowell

I'll do it too. I don't know about my mom and my sister, but I'll do it. I'll have my father's body burned into ashes. I'll pack this ash into paper bags. The morbid joker has already made the molds. I'll go to the mountains with my mother and my sister, bringing the cannon as he asks. I will plunge his remains into the barrel and point it into a hill so he doesn't take anyone with him. I will light the fuse, but I will not cover my ears, because when I blow what used to be my dad into the earth, I want it to hurt.

[MUSIC - "FATHER DEATH BLUES" BY ALLEN GINSBERG]

Act Two: Fists And Guns

Ira Glass

Act Two, Fists and Guns. Drive-by shootings and tragic assaults where one teenager shoots another for a jacket or a pair of Nikes are such old news that we forget how we got to this point. Geoffrey Canada grew up in a tough neighborhood in the South Bronx before guns were commonplace in teenage culture there. He's also been a gun owner himself. We wanted to talk to him about that, but first, a few words about the days before guns.

Geoffrey Canada

I'll tell you, it was an absolute shock for me and my brothers when we moved from a relatively quiet area of the South Bronx, to what to us looked like a children's paradise, with children playing in the streets and games. And we moved on the third floor on the front of the building.

And I remember my brothers and I, we were waving at the little boys and girls from our window, waiting to go downstairs and make some friends. And one of the boys, they looked up, and he pointed his finger at me, took his fist, balled it into a fist, and rubbed it in his eye, and pointed back at me. And I remember looking at my brothers and saying, you know, I think that boy wants to beat us up. And we were stunned. We were like, for what? Why would they want to fight us?

And we went to our mother, and we told her, Ma, I think the boys want to beat us up downstairs. And you know how mothers are. She was like, oh, don't be foolish. You don't even know those boys. Why would they want to beat you up? Just go down there and play. And we realized we were literally on our own with this. And it was from that initial introduction, each one of us had to go downstairs, have a fight, before we were accepted on the block.

And when I look back on it, it was like you had to see where you fit in into a hierarchy in terms of being able to fight. And once that was established, you were pretty much OK on the block.

Ira Glass

One of the things that you write about is that you say that the older boys on the block when you grew up would set the younger boys fighting.

Geoffrey Canada

That's correct. And you know, it seemed awfully cruel to me before I knew sort of what I call the codes of violence that existed at that time. That we would just be sitting around, and the older boys would just really set us up to fight one another. They would just simply start, Rodney, can you beat Geoff? And Rodney would say, I don't know. And he'd say, well you scared of him? And he says, I'm not scared of him. They say, well Geoff, you scared of him? He's like, I'm not. And you were just trapped, and I would be sitting there thinking, why are they doing this? Why me and Rodney? We were just friends, and the next thing you know we'd be having a fistfight.

Later I found out that the older boys really felt it was their responsibility to teach us how to fight, because if we didn't learn it on Union Avenue, which was the block I grew up on in the South Bronx, then the other kids from Home Street, and Prospect Avenue, 157th Street, they would take advantage of us. But this was really largely fistfighting between kids that had rules around them.

In my neighborhood there was no wrestling allowed in a fight, and the kids would break it up if you started to wrestle. They'd be like, no, no, that's not fair. No. I have no idea. In another place, it was totally all right. But we really believed in these rules. And in the end the worst that would happen was maybe a kid would get a bloody nose, but no real long-lasting damage to you.

Ira Glass

Explain what the other rules were. What were other parts of the code of conduct?

Geoffrey Canada

When I was growing up, you had to fight somebody your own size. I mean, there was a real thing that people would say you couldn't pick on somebody smaller than you. And people really reinforced this, and they would say, why are you bothering him? He's not your size. You can pick on me. I'm your size. And people really believed that. You couldn't fight girls, and these were pretty well-understood by the other members of our youth community.

Ira Glass

One of the things about this whole system is that you could have a fight, and you could lose, and you could still maintain face.

Geoffrey Canada

Oh, absolutely. There was no real shame in losing a fight if you fought well and courageously, and someone was just more skilled than you. Indeed, once that was established, you could accept the fact that someone could beat you. And people would just ask, can you beat Tommy? And I would be like, no. And it was no big deal. They would just say, OK, Tommy's more skilled. But it didn't mean that under certain conditions I wouldn't fight Tommy.

Ira Glass

And so there were checks on violence.

Geoffrey Canada

They really were. And typically there were not what I would consider to be a lot of random fights. Every now and then there'd be some fight between two guys who were trying to work something out, but basically everybody learned where they were in the pecking order, and we established some levels of comfort with one another.

Ira Glass

Now with more guns on the street, what has happened to that system of checks?

Geoffrey Canada

Well, you know it's really changed dramatically. One of the things that happens when you have a handgun is that you don't have to think about the consequences of your behavior that leads you into a confrontation. And what I mean by that is that we actually had to think when we said something back. If we were walking down the block and somebody said something to us, and they were bigger than us, we had to think, jeez, if say something to this guy, am I really prepared to go fight him? And often the case was no, I don't think so. So I'm going to pretend I didn't hear it. With the handgun, you can really say, I don't care how big somebody is. No one's going to say that to me. And when someone does, you stop, and you say, who are you talking to? And you're prepared to take it to the next level.

Ira Glass

In your book Fist Stick Knife Gun there comes a point where you talk about when you got a handgun yourself. Let me ask you to read 101 in your book.

Geoffrey Canada

Terrific, I'm going to read Chapter 14, part of it.

In 1971, well before the explosion of handguns on the streets of New York City, I bought a handgun. I bought the gun legally in Maine where I was in college. The clerk only wanted to see some proof of residency, and my Bowdoin College ID card was sufficient. The gun was exactly what I needed. It was so small I could slip into my coat pocket or pants pocket.

I needed the gun because we had moved from Union Avenue to 183rd Street in the Bronx, but I still traveled back to Union Avenue during the holidays when I was home from school. The trip involved walking through some increasingly dangerous territory. New York City was going through one of its gang phases, and several new ones had sprung up in the Bronx.

One of the gangs liked to hang out right down the block from where we now lived on 183rd Street and Park Avenue. When I first went away to school, I paid no mind to the large group of kids that I used to pass on my way to the store or to the bus stop back to the Bronx. The kids were young, 14 or 15 years old. At 19 I was hardly worried about a bunch of street kids who thought they were tough, but over the course of the next year the kids got bolder and more vicious. On several occasions I watched with alarm as swarms of teenagers pummeled adults who had crossed them in one way or another. Everyone knew they were a force to be reckoned with, and many a man and woman crossed the street or walked around the block to keep from having to walk past them.

And I crossed the street also, and there were times that I went out of my way to go to another store rather than walk past a rowdy group of boys who seemed to own the block. On more than one occasion I rounded the corner only to come face to face with the gang. I could feel their eyes on me as I looked straight ahead, hoping none of them would pick a fight.

After having survived growing up in the Bronx, here I was scared to go home and walk down my own block. The solution was simple. I had a gun. I had a gun and an attitude. When I look back on the power the gun had over my personality and my judgment, I am amazed. It didn't happen all at once. The change was subtle. At first I continue to avoid the gang of teenagers. I crossed the street or turned down another block when I saw them.

But slowly, as I carried the gun with me day after day, my attitude began to change. I begin to think, why should I have to walk an extra block? Why should I feel that I have to cross the street or look down when I pass those kids? By the end of two weeks, I had convinced myself that all of the habits I had cultivated to avoid conflict with the gang were unnecessarily conciliatory.

My behavior when I went outside began to change. I stopped going out of my way, or crossing the street, or avoiding eye contact when I passed the gang. In fact, I began to do the opposite. I would choose to go to the grocery store on the side of the street where the gang was gathered. I would walk through them head up, eyes challenging, hand in my coat pocket, finger on the trigger. I was prepared to shoot to kill to defend myself. My rationale was that I was minding my own business, not bothering anyone, but I wasn't going to take any stuff from anyone. If they decided to jump me, well they would get what they deserved.

I was lucky that winter break. The time quickly came for me to go back to college and no member of the gang had felt the need to challenge a strange young man with fire in his eyes and his hand always in his coat pocket. I knew if I continued to carry the gun in the Bronx, it would simply be a matter of time before I was forced to use it. My behavior would become more and more reckless each day. I unloaded the gun, wrapped it in a newspaper, took it to the town dump, and threw it away.

Ira Glass

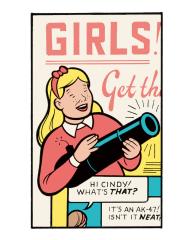

Geoffrey Canada reading from his book Fist Stick Knife Gun. Geoffrey Canada says that the kind of fistfights that he grew up with ended in the Bronx in the 1970s. At one point in his book, he's told that one reason for the increase of handguns in the hands of teenagers is because the gun manufacturers, after saturating the market of white males, started to market guns to women and to young people.

Geoffrey Canada

It was absolutely-- for me it was a devastating discovery, because I was just really mortified to find out that what I considered to be my young people accidentally figuring out how to find these handguns through some hard looking and digging around in the inner cities was actually a marketing campaign that was aimed directly at them. And they started to change the names of handguns to make them more attractive to kids.

Ira Glass

Names like Viper, you say in the book.

Geoffrey Canada

Yes, and they weren't finding these handguns. The handgun manufacturers were finding my kids. And it was not a small campaign. It was funded by millions of dollars.

Ira Glass

Can you imagine what you would have thought as a kid if when you were 7 you would know that someday decades later you would be sitting in a studio? You would be writing a book about how much better it was back then?

Geoffrey Canada

Yes. No, absolutely I could not have imagined doing that. And it's one of the things that really shocked me so much, was that I remember these times as being so tough. But yet I have to agree that this is tougher. It is tougher when you're dealing with the fact of you could die than when you're dealing with the fact that you could get beat up. Both are horrible for children, and I don't want to pretend that it's not damaging to a child emotionally to grow up fearing for their physical safety. It's just more damaging to grow up fearing that you're going to be killed.

Ira Glass

Geoffrey Canada is the author of Fist Stick Knife Gun, A Personal History of Violence in America. He now runs one of the most ambitious programs in the country to help children in neighborhoods like the one he grew up in, the Harlem Children's Zone, which is remaking 100 blocks in central Harlem, and his model the Obama administration is planning to use across the country.

Coming up, what it's like getting shot, and what it's like to sell guns to criminals. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International when our program continues.

Act Three: Shooter

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week on our program, of course, we choose a theme and bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's program, guns and the people who love them. We are at Act Three of our program. Round three, Shooter. This next story I think is the quintessential gun story because it is both about the fear of guns and the desire for them, the pleasure people take in them. A Chicago playwright named Bryn Magnus told this story on stage here in Chicago. As a kid growing up in Wisconsin, Bryn Magnus was terrorized by a bully named Dennis Schultz who used to beat him up all the time.

Bryn Magnus

So he would pound on me really bad, and I would take it year after year, and I would get pretty good at looking wounded so he would stop sooner. But anyway, one day I was with his cousin Kurt Schultz and Marky Welkirk and a couple of other guys at Kurt Schultz's house in his bedroom, and we were smoking pot and listening to Pink Floyd. And the door kicked open, and it was Dennis, and he had his father's Luger pistol.

And he turned and he said, Smokey, Smokey, and then he shot Kurt Schultz in the head. And Kurt flipped over the chair he was sitting in back like that, and we all totally freaked out, and I dove out the window. I just felt glass shattering around me, and I started running. And as I was running down the street, I heard Dennis Schultz scream, get your ass back here, faggot. And I was like oh God, I've got to get away from this guy.

Anyway, I'm running, and he had come out of the room after me through the window. And I was running down the street, and I heard a shot, and I heard the bullet whistling past me, and I was running as fast as I could. And then I didn't hear the shot that hit me. I just felt this sting in my back, and it kind of looked like this. The shot spun me around, and I landed, and he came running up to me, and he stood over me with the Luger. And he said-- I don't even know what he said actually, because I had by this time soiled my pants, and I was really shaking. And this was no act. I was really frightened.

And he just shot me like five times in the stomach, and I felt each time it hit me. I felt it striking me, and I looked down, and it was like wax. He had taken the bullets out of these bullets and dripped in wax over the gunpowder and put them back in this Luger. And he had done this act of terrorism, which I thought was really exceptionally creative.

Instantly conscripted my next door neighbor, Chris Williams, to steal his father's .38 Police Special from his bedroom that night, and we spent like hours making these bullets. We'd take the lead out of the bullet, and we'd drip a little-- well, first we'd dump a little of the gunpowder out, and then we'd drip a little wax in there, and then we'd put a little ketchup or fake blood in there, and then we'd drip a little more wax on top. And we had it all figured out.

And so then we would go out into the countryside on these country roads in Wisconsin that had these really twisty, turny things. And we would scope it out. We'd watch the cars go by, and make sure that we had the sight lines all right, and then we would enact these great scenes where one of us would have the gun and the other would be running or standing there like, oh no. So the car would come around the corner and hit us with its light, and it would be like this boom, and ah, and fall. The car would screech to a halt, and then we'd get up and run away, and it was really a great time.

And we did one where we were standing in the road, and I was the one who got shot. And usually what happens is the car stops like 1,000 yards before he gets to you and then waits until nothing's happening, and then slowly goes past. Well this car drove right up, and it was a police car. And these cops get out, and they have strong flashlights, so they can see us laughing in the bushes.

And they come over to us, and they weren't too afraid, because by that time we were so afraid. They didn't think that we were going to do anything with this gun, but they said, what are you kids doing?

And we told them what we were doing, and he said, oh yeah? Let me see. So I said, OK. So I had Chris set up, and we got all set, and these cops were standing there with their flashlights on us. And Chris shoots me, and I fall to the ground doing my thing. And there's this moment of silence, and the cop goes, yeah, that's pretty good. Do you guys do parties?

Ira Glass

Bryn Magnus recently finished his screenplay, not yet produced, about a morally invisible banker.

Act Four: Potato Potahto

Ira Glass

Act Four, Potato Potahto. Now the story of two people nearly killed in gun attacks, two people who drew very different conclusions from their experiences. The first one we're going to hear from is Mike Robbins, a Chicago police officer, who in 1994 was shot 11 times. One bullet that ripped through his abdomen is still lodged an inch from his spine. A quick warning before we begin. Some of this might not be suitable for small children.

Robbins was working in the Gang Crimes Unit for the Chicago police. He and his partner answered a call about a gang disturbance. Shots had been heard. They drove down a dark alley. Robbins was driving, and somebody ran up to his side of the car.

Mike Robbins

It happened so fast, my partner and I didn't get a chance to respond. My partner had his gun out. I had my gun out. And this individual just stuck the gun in the window and immediately began shooting, and stuck the gun into my chest repeatedly, several times point blank just stuck it into my chest and fired.

Ira Glass

And he's shooting you in the chest. Were you wearing a bulletproof vest?

Mike Robbins

Yes, I was wearing a bulletproof vest. And in effect it's like basically someone taking a cannon and putting it in your chest and firing. That's exactly how hard it is. It's like a horse maybe or an elephant kicking you in the chest very hard, very painful.

Suzanna Hupp

Basically in '91 my parents and I had gone to eat at a local restaurant on a bright, sunny day like today. We certainly weren't in a dark alley somewhere where we weren't supposed to be.

Ira Glass

This is Suzanna Gratia Hupp, a chiropractor in Texas and a gun owner.

Suzanna Hupp

And a crowded restaurant-- it was payday, and it was the day after Boss' Day, a place that we went all the time. In fact, the manager that day had invited me. We were done eating, and all of a sudden this guy crashes his truck through the window, and we promptly heard gunshots. And when we heard that, your first thought is robbery. It's a crowded place. It's a robbery.

So we immediately drop down. My father and I put the table up in front of us. But about 45 seconds into it, I'm going to say probably six people were killed at that point. He was not spraying bullets. He was simply walking from one person to the other, aiming, and pulling the trigger.

Mike Robbins

In my case, the individual, I could never forget his face because his face was closer than yours and mine.

Ira Glass

And was he cold and clinical about it, or was he just angry?

Mike Robbins

Very much so.

Ira Glass

He was clinical?

Mike Robbins

Very cold, very clinical, and just shooting, shooting repeatedly. My partner was shot six times. We screamed and hollered in the car at each other. There was just a lot of screaming and hollering. Some of the things were inaudible. We're going to die. We're going to die. Help me. Tell my mother I love her. I love you. I told him that I love you, and he told me he loved me.

Suzanna Hupp

Actually you would have expected it to be pandemonium, but no, it was very quiet, in fact. And you can ask anybody about that particular day. It was oddly quiet. You'd hear an occasional scream or an occasional moan or an occasional instruction shouted, like get down or something like that.

Ira Glass

But otherwise it was just completely silent?

Suzanna Hupp

Yes.

Mike Robbins

I felt it took forever. The shooting was like in slow motion. When I look back at it in retrospect, I see things very slowly now.

Suzanna Hupp

At this point he was about 15 feet from us. He was about 3/4 of his back turned toward me. I had a place to rest my arm. It was a perfect opportunity.

Ira Glass

Perfect shot.

Suzanna Hupp

And then I realized that a few months earlier I made the stupidest decision of my life. My gun was 100 yards away in my car, completely useless to me, because I had chosen to obey Texas laws.

Mike Robbins

My partner couldn't get a shot off at a guy on the side because he was-- as he explained to me later on, I was busy bouncing up and down in the car back and forth and up and down, that if he'd have shot, he probably would've shot me.

Suzanna Hupp

Well at that point my father began to raise up and say, I got to do something. I got to do something. He's going to kill everybody in here. And my attention turned to him, and I started grabbing him by the shirt and pulling him down.

Mike Robbins

All the strength had been blown out of me, literally. I could no longer struggle or fight with this individual.

Suzanna Hupp

But when he saw what he thought was an opportunity, he jumped up and ran at the guy. Well, the guy saw my dad coming. He turned, pulled the trigger, shot my father in the chest.

Mike Robbins

And I felt that this is the way I was going to die, and this is how it feels to die. These things were running through my mind as he was shooting.

Suzanna Hupp

I stood up and I grabbed my mother by the shirt collar, and I said, come on, come on, we've got to run. We've got to get out of here. And my feet grew wings, and I was one of the only people out of the front area there to make it out of the back.

Ira Glass

How many people were killed that day?

Suzanna Hupp

About 23 people. And I turned around to say something to my mother, and realized that she had not followed me out.

Mike Robbins

One of the interesting things that happened was that I saw a vision of my mother at the time when we were shot. And my mother had passed in 1982. And if we have time I could tell you, but it doesn't take too long. But at the time when this individual was shooting and shooting and shooting in our car, I somehow mustered enough strength to turn my body to the left. And when I did so, my mother just was in the back of the car, and she just grabbed me and pulled me right to her bosom, and just pulled my head right into her chest. She had no clothes on at all. She just pulled me right to her bare breasts, and just pulled me close.

And at that time there was another loud bang and a big kick in my back. And he had shot me in the left side of my back in the shoulder blade, I found out later on. And then my mother had released me, and at that time the individual who was doing the shooting, he took off running down the alley.

Suzanna Hupp

And I later learned from the cops my mother had crawled over to where my father was, and was cradling him until the gunman got back around to her. And they said he put the gun to her head, she looked up at him and put her head down, and he pulled the trigger.

Mike Robbins

Well, just prior to the trial as we were being prepped by the state attorney's office, they were asking what happened next, and what happened next, and what happened next. And I explained to them, and I explained to them just like I mentioned to you about my mother appearing and pulling me close to her. And they advised me not to do so.

Ira Glass

Not to mention that on the stand.

Mike Robbins

Not to mention that on the stand, because they did not want to prejudice the jury or put anything into their mind, and perhaps them thinking that maybe I was suffering a period of delusion, and if doing so, then maybe I wouldn't recognize this individual who shot me. So at the time when I went on the stand, I told the jury that I had saw my mother. I told them the very same thing. I didn't want to hide it at all.

My reason for saying is that to deny that this happened would be to deny that I saw my mother, to deny that God exists. And I did not want to do that. I don't think that I would be able to live with myself. I would've been better off dead. The individual might as well have just shot me and killed me.

Ira Glass

Mike Robbins came out of the experience a firm advocate for stricter gun control. He got rid of his own guns and began speaking around the country about the issue. Suzanna Gratia Hupp meanwhile became a visible and important spokesperson in the fight to change the gun laws in Texas to allow concealed weapons. Soon after her side won and concealed weapons became legal in Texas, she was elected as a state representative.

Ira Glass

What do you make of somebody who goes through something very similar to what you went through and concludes the opposite?

Suzanna Hupp

Well, I don't mean to chuckle. I guess I've just heard this sort of thing so many times, but it does kind of floor me. What I don't understand is that their logic seems to stop at the point that they think the gun is the bad guy. Somebody that you're already talking about is willing to overlook the highest law of the land, which is taking somebody's life. That somebody who is willing to overlook that law will allow a silly little paperwork law, a gun law, to stop them from murdering somebody.

Ira Glass

If they want to kill somebody, they're not going to really worry about whether or not they can carry a concealed weapon.

Suzanna Hupp

That seems insane to me.

Ira Glass

Let me ask you a question. One of the people who we are interviewing for our show is a woman who is now a state representative in Texas. And she had an incident where both her parents were shot, where she was almost shot. And what she concluded from that was that she should be able to carry a gun because she could've actually shot the guy.

Mike Robbins

How can you conclude from one incident that everyone in the total state of Texas should have a gun?

Ira Glass

What would you say to her, though? I mean, she said that if she had had a gun at that time-- like what would you want to say to her?

Mike Robbins

Well, anyone can say could have, should have, would have. Anyone can say that. I mean, this is America. You're entitled to say whatever it is you want. You have that First Amendment privilege, freedom of speech.

Ira Glass

I'm thinking about it. I'm thinking like one of the differences between your experience and hers is that when she and her parents were in this experience where they were shot at, she didn't have her gun. But you and your partner, you two men, you both had guns.

Mike Robbins

We both had guns, and it didn't protect us.

Suzanna Hupp

OK, a gun is not a guarantee. It's not a guarantee. I'm not telling you it's a guarantee. There are going to be times-- and I tell you, one of the things that I dread is something happening to me, my being, God forbid, murdered at some point, and my being found with the gun somewhere in my possession, because I know people who are anti-gun will use that for all it's worth. And that's probably one of my biggest fears. And the fact--

Ira Glass

Not that you would get murdered, but that you'd get murdered with the gun, and that you'll be used as propaganda?

Suzanna Hupp

Yes. Yes, and I have to say a thousand times over, it's not a guarantee. It simply changes the odds.

[MUSIC - "JANIE'S GOT A GUN" BY AEROSMITH]

Act Five: Straw Man

Ira Glass

Act Five, Straw Man. The guns that are used in crimes are the guns that give guns a bad name. And where do those guns come from? Well, most of us assume that they're stolen, but in fact, according to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, only 10% of the guns confiscated at crimes are stolen. Where do the rest come from? 60% are purchased legally. Tori Marlan wrote about this when she was a staff writer at the Chicago Reader.

Tori Marlan

Most of them are acquired by a means called straw purchasing, and that means that they are purchased by someone who is legally able to buy the gun for someone who is legally unable to buy the gun.

Ira Glass

So in other words, somebody without a criminal record would go and purchase a gun for somebody who does have a criminal record.

Tori Marlan

Right.

Ira Glass

And so why is this so hard to stop?

Tori Marlan

Because it's nearly impossible to detect. It's hard to stop a straw purchase in action, because the only way ATF knows that somebody's been straw purchasing is if that person's guns start turning up in crimes, and they're traced back to that person.

Ira Glass

For an article in the Chicago Reader, Tori Marlan interviewed a straw purchaser who bought guns for guys in his neighborhood between 1988 and 1990, and then he was caught. He served 13 months for dealing firearms without a license. She agreed to re-interview him on tape for This American Life.

Straw Purchaser

Well, the first time I was like walking down the street, and this guy seemed to know who I was, because I used to be a security officer. So he approached me, and he offered me $200 dollars to buy a gun. And I thought that was quite a bit of money for me to keep in my pocket.

Tori Marlan

Were you working at the time? I mean, did you have a steady income?

Straw Purchaser

No, at the time I wasn't working. So I went on and did that. I told him I wouldn't do it again. I'd just take the $200 and go and buy him a gun.

Tori Marlan

What did you know about him?

Straw Purchaser

Well, I knew for one thing that he dealt drugs. That's about it. I'd never known him to be a violent guy or anything like that, so I figured that it was just something that he was using for his protection. I had known many drug dealers that had had guns and used them just for their protection. They didn't go around hurting people or anything.

I thought it might not be a good idea to do, but the same time I was broke. I figured I wasn't going to do it again anyway, so I might as well do it this one time, get the money, and go ahead on about my business.

Tori Marlan

What were the reasons that you thought it might not be such a good idea?

Straw Purchaser

Well, I forgot that if someone did get shot with the gun, it may well could be traced back to me. But seeing that those guns, they don't usually try to trace them unless it was a murder. And even then, as long as they got the person that did it, they wouldn't much care where the gun came from.

Tori Marlan

So tell me about the day that you went to purchase the gun. Was he with you?

Straw Purchaser

Yes, he was with me. And we went out there and kind of like just bought the gun and came on back. It wasn't no big deal.

Tori Marlan

Did the guy that you were buying the gun for handle the gun? Did he pick out the gun, and did the gun dealer to your knowledge have any suspicion about the sale that he was making?

Straw Purchaser

Well, he did pick the gun out. But see, the suspicion was thrown off because he did it in such a way that it was like I was buying it. I knew basically what kind he wanted, so we was looking at the guns. And I guess when we saw a couple of them, and he agreed, I agreed, and it was like an agreement that was understood by me and him more so than the dealer. From that point on, he must have had spread the word around, because a couple of guys in the neighborhood started approaching me, and I didn't think that was a good idea.

Tori Marlan

Did you know the guys who started approaching you?

Straw Purchaser

Yes, I did know them.

Tori Marlan

What did you know of them?

Straw Purchaser

That they basically were the same type of guys. They dealt their little drugs here and there, so I didn't really think it was nothing that they was doing that was shooting people and stuff like that. They just probably wanted their protection. They wanted to just have something for protection just like any citizen would, even though they was kind of like the underworld of citizens.

Tori Marlan

So how many guns did you eventually supply to these guys?

Straw Purchaser

Well, as time went on over a period of two years, I believe it was something like 60. It was in the area of 60 guns.

Tori Marlan

And how much money would you make from the purchases?

Straw Purchaser

Well, as time went on it became lesser than that $200, I would say from $50 to $100. It jumped all the way down. That first guy, when he came along with that deal, it was like something I guess to get me started or something. I don't know. Or something that I would do just because of the money. It was like too much to resist, stuff like that.

Because I would say first of all the money came first. And the respect that I was given from the neighborhood guys, that that was another thing. It was a different story from back in the old days when-- because I didn't get that much respect.

Tori Marlan

What do you mean? How did that change for you? In what ways were they showing their respect?

Straw Purchaser

Well, they were showing it in more obvious ways. There was always guys that never had said anything to me before was now-- oh, my buddy here, shaking my hand, and you want a drink or something? Just stuff like that. So I was getting a lot of recognition. That felt good too. Like I say, sometimes it was for the wrong thing. You get all this good recognition for the wrong thing.

Tori Marlan

Did you ever wonder what was going to happen to the guns? I mean, did you really believe that the drug dealers wouldn't use them, or would only use them for their own protection? Did you at any time wonder if they were involved in maybe more serious criminal activity, something that would harm people?

Straw Purchaser

Yes, I did begin to wonder and think that they will probably be harming someone with them, because some of these guys didn't look as nice as they should look, so I figured that even though they was just dealing drugs, they might be more than just drug dealers. And I wanted to get out of that racket for sure, but I couldn't just-- I wanted to tell them that I had lost my gun card, or it got shreded or anything. But I ended up not being a good liar, I guess.

Tori Marlan

Did you actually try?

Straw Purchaser

Well no, I didn't. I didn't.

Tori Marlan

Did you ever hear about the guns being used in crimes?

Straw Purchaser

Yes, I did. A few were used in crimes I heard of. The shootings that I did know about always happened because someone was trying to either stick up one of those dealers, and then ended up getting shot themselves. That's all. It wasn't too much other than that.

Well, there was once a wild shooting spree that happened, but I think a couple of people did get shot, but no one got killed. I never knew of any murder exactly, although those federal guys did tell me there was a murder on one of them. But it was like out of state or something.

Tori Marlan

So were you living off of the income that you were making from buying the guns?

Straw Purchaser

Yes, I was living off of that, and probably a little public aid, general assistance.

Tori Marlan

So how much would you estimate that you made in the two years that you were buying the guns?

Straw Purchaser

I never really gave that a good thought, but I know it would have been somewhere in the $4,000 or $5,000 range.

Tori Marlan

So you weren't getting rich off of this.

Straw Purchaser

No way. It was just something to keep my head above water.

Ira Glass

This straw purchaser was interviewed by Tori Marlan. Only 14 of his guns, out of over 60, have been recovered by police.

Credits

Ira Glass

Well, our program was produced today by Julie Snyder and myself with Alix Spiegel and Nancy Updike. Senior editor for this show, Paul Tough. Contributing editors Jack Hitt, Margy Rochlin, and consigliere Sarah Vowell. Production help from Alex Blumberg, Rachel Howard, Laura Baggett, and Brian Reed.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

Today's program was first broadcast in 1997. Mike Robbins, the police officer who you heard in Act Four of the show, died a decade after that first broadcast. He died in 2008. He was 57. He volunteered with kids in Chicago and remained a vocal activist for stricter handgun control until his death.

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. WBEZ management oversight for our program by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia, who describes the first time here at public radio this way.

Sarah Vowell

The sound it made was as big as God. It kicked little me back to the ground like a bully, like a foe. It hurt.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of this American life.

Announcer

PRI, Public Radio International.