239: Lost in America

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

So many of us, we wander through this country. We wander through our lives. We wander in darkness. Often we feel lost. Like Chris. He was doing pretty badly. Living on the street. Hair to his shoulders.

Chris Sewell

I called it the Unabomber look. I was just living in the woods. Just an open wooded area at the corner of Pond Drive and Route 347. I'd have fresh clothes on usually, but I only could do the wash every so often, and they were outside, so I smelled like the great outdoors, whether I liked that fact or not. And I very much knew I needed medical help.

Ira Glass

So Chris needed this medical help, but of course, he had no money to pay for the medical help. He made money collecting cans and bottles on the street. Whenever he'd go to doctors or social services, he was so wacked-out looking that they wouldn't even talk to him like a person. They wouldn't even look him in the eye. It's a hell of a thing, isn't it? Wanting eye contact, not getting it. But then if you're lucky, somebody puts up the lights.

[AUDIENCE CLAPPING]

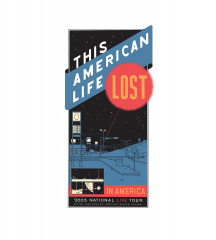

Welcome. WBEZ Chicago. It's This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass. Our program today recorded on a live tour of five cities: Boston, Washington DC, Portland, Oregon, Denver, and our hometown, Chicago.

[AUDIENCE CHEERING]

So Chris was stuck. He needed money to go to a doctor. And then he got this idea. He remembered how a couple years before that, he had wandered off the street into a shopping mall to get warm, and there the State of New York had set up two laptop computers on a folding table.

Chris Sewell

And to see the lady just look at me, nod her head, and smile when I walked up to the booth, like I was just one of anybody, was great.

Ira Glass

So he sits down at the computers, and on these two computers you could look up your name and see whether the state was holding money for you that you did not know about. And there was all sorts of money. Utility bill refunds, tax refunds, lost checks, owed to all sorts of people and institutions. Lost money. Or not even lost, since most people didn't even know it was missing. This is like money in purgatory. This is money in limbo.

And thinking about all this, Chris Sewell realized how he could pay for his doctors. He would look online, find money of theirs that they did not know about, money that the state was holding for them, and then he would present that to them.

Chris Sewell

Well, I was hoping that I would suddenly get a couple of phone calls and a couple of checks, and people say, "oh, wow, thanks for having done this." And then I was hoping that these doctors would just even talk to me in a civil manner. And then work my way up from there.

Ira Glass

Now the crucial fact that I have to tell you about Chris Sewell at this point in the story is Chris is great at finding other people's money in these databases on the internet. And when he looked for money for the doctors at his local university hospital, not only did he find hundreds, hundreds of unclaimed Blue Cross Blue Shield checks, reimbursements, lost trust fund checks. He also found 100 checks that were owed to the hospital itself. It was a huge victory.

But when he went to the hospital to tell the doctors there that there was this money out there for them, he always got the same reaction.

Chris Sewell

There was a total wall of silence. Except for the people who were telling me to buzz off. I actually went out and I printed out the claim forms. And I had a cover letter for it. And tried, in my own humble fashion, to appear professional. I went to the Salvation Army, bought myself a blue pinstripe suit. Even with my long hair and my beard, I went around and hand-delivered all of them.

Ira Glass

And how did that work?

Chris Sewell

That was the one that-- it didn't work. I didn't get responses. There was no conversation. As soon as I talked, security people would just appear out of the woodwork.

Ira Glass

He tried letters. He tried emailing. Everybody just thought it was a scam. Eventually he got doctors to help him out through other means. And then he turned this talent elsewhere. He used it wherever and whenever he could. When his local public TV station was doing the pledge drive, he couldn't actually give money, of course, but he looked online, found $1,000 of theirs, called them up.

In setting up this interview for our radio show, he was talking to one of our producers on the phone, Julie Snyder, and while he's on the phone with her, he found $400 bucks owed to WBEZ, the radio station where we work. And using nothing more than a normal internet connection, he found $610,940 owed to the City of New York. So much money that the city comptroller honored him with an old fashioned letter of commendation. Who knew that that was a real thing, and not just something that Commissioner Gordon would give to Batman now and then?

And a press conference. It's impossible to overstate what that meant to him, that press conference.

Chris Sewell

I was extremely nervous. And there were big security lines. And I finally got there and walked into a room full of TV cameras. And I don't think I'd spoken to anybody before that in like two weeks.

Ira Glass

You hadn't spoken with anybody at all for two weeks? For two weeks you hadn't had a conversation with another person?

Chris Sewell

Yeah. Again, I don't have a lot of friends where I live. I'm, you know-- trying to just reach out in the middle of a social void is very difficult. I mean, on the street, I think my record one time was I don't think I'd spoken to anybody for something like three months.

And I just-- I sort of tried to put a party face and soak it all in and radiate it back as best I could.

The city comptroller actually recognized me. I feel that I've somehow helped create a place for myself in society, that I'm somehow a little less lost. I'm creating a purpose for my own life, and a direction.

Ira Glass

Our program today: Lost in America. Stories of people who are lost, and how they sometimes, temporarily, if they're lucky, get found. On our program today, Sarah Vowell finds a terrorist, hiding and lost in a patriotic song. Jonathan Goldstein tries to lose something and finds that it is harder than it seems. And there is an entire magazine devoted to writing that people have lost, dropped, thrown away, and tried to destroy. Its creator reads samples on stage. Plus Jon Langford of the Mekons, the band OK Go and more. Stay with us.

[AUDIENCE CHEERING]

Act One: Losing It

Ira Glass

Act One. Losing It.

Well, if you're going to do a program about people who are lost, you pretty much have to do a story about adolescence. Jonathan Goldstein is a regular contributor to our show. A quick warning before we begin, for parents listening with kids, he talks about sex in this story. Please welcome Jonathan Goldstein.

[AUDIENCE CHEERING]

Jonathan Goldstein

Dying a virgin happened to people. Hans Christian Andersen, Queen Elizabeth the First. My grandmother's prophetically named brother, Uncle Hymen.

And I knew it was the kind of thing that could happen to me. Days would turn into months, months into years, and eventually I would drop dead in a men's hotel and be buried sexless in a single cemetery plot squeezed in on my side between my parents. And so I began, at an early age, what I thought of as my life's work, the work of not dying a virgin.

At 10 I met Varid, my first crush. She was in from Israel with her family, and was staying with our neighbors. Since this was the summer Grease came out, I invited Varid upstairs to our living room, where I played the soundtrack on our stereo. While it played, I danced for her. My feeling was that you had to give girls everything you had-- your showmanship, your best moves, even your dignity.

As the music played, Varid sat there with quiet indifference. At one point, I tried to bring her soul to life by lying down on our coffee table and spinning around on my stomach like a spastic Lazy Susan. When I did the splits, I fell to the ground with a ferocity that almost tore my scrotal sac in two.

Before Varid went back to Israel, I handed her all 10 Archie digests that I owned. I stacked them so all the spines lined up perfectly. I wanted them to look solemn and substantial, like a package wrapped in rope from the old country. "It's how I feel about you," I wanted to say, but her English was not good enough to understand. For the next several years, I would say some variation of these words to many different people, but no one's English was ever good enough to understand.

At the age of 13, I entered the service industry. The self service industry. I spent all of my time listening to music like Yellow while fantasizing about the high school gym teacher play tether ball in her brassiere. Or Stevie Nicks strumming a guitar in her brassiere. Or in my darker moments, Golda Meir ruling a nation in her brassiere.

And then at 14 our family got one of those early model elephantine video machines. I rented early 80s teen sex comedies like Private Lessons, Private School for Girls, and Reform School Girl. I would make each 20-second shower scene last anywhere from six to seven hours. Pause, rewind, frame advance became my version of the holy trinity. One time, having lost the remote control to our VCR, I watched the entirety of Sorority Girls on Vacation lying on the basement floor with the VCR on my chest, hitting its buttons like a 70 pound accordion.

It was around that time, inspired by a potent cocktail of sexual desperation and movies starring Phoebe Cates, that I left the comfort of home for the streets. A 4 foot, 10 inch, pheromone-drenched Cabbage Patch doll with acne on the prowl. And thus at 16, I met Tamara. Everyone had a locker partner at our school, and I shared mine with Tamara. Just knowing that no matter what, our winter boots were alone in the dark together for six hours a day was enough to make me feel at least that something in my life was going all right.

One day I finally worked up the courage to ask her if she wanted to see the Eurythmics concert with me, because I knew she was a big fan, and she said yes. I don't know where I came up with the idea, but I had decided at some point during the concert that I wanted to hold Tamara from behind and sway with her back and forth to the music. It was all I could think about all night. It wasn't a kiss or a held hand I was after, but something else, something less definable. It was like I wanted to prove that I could get us into some kind of groove.

Finally, during a slow song, I snuck up behind her and put my sweaty pocket hands on her hips. I tried to ease us into it. My movements were halted and completely non-musical. Rather than dancing, it looked like I was trying to hoist a resistant woman into a mailbox while in the throes of a painful piles attack. Tamara freed herself, and for the rest of the evening, she was afraid to come near me.

At home that night I ate a bowl of cold cereal was staring at a bottle of my mother's nail polish on the kitchen counter. Carefully I painted my nails. In bed, my fingers spider-walked the length of my ribs. "Quit tickling me," I told myself. "I have to make this an early night." I grabbed my hand and flung it away from myself roughly. but it always crept back.

If early 80s teen sex comedies had taught me anything, which, unfortunately, they had in abundance, it was that college was going to be a nonstop nookie fest. I wasn't fat enough to be the one who sees undressing sorority girls shortly before falling backwards from a ladder. Nor was I daring enough to have sex with a friend's mom. Nor was I near sighted and good enough at science to create a fellatio bot.

But I did know that I was the nice guy, the one that drove everyone around on their way to getting action, and that before the credits rolled, I would receive my due. It was only right. Well, the credits had rolled, the curtain had come down, there was a man sweeping up popcorn, and still no due.

For winter break, my friend Howard and I decided to spend the week in New York City. As we rode the train there, we passed a burned out school bus in a field, and I thought, yes, that is my heart. My heart is a burned out school bus with no windows sitting in the middle of nowhere. But then after about 15 minutes, the train passed a little gray wooden control booth, the door flung wide open, and I thought, no, that. That is my heart.

The train continued along through February fields, and I looked for more things to call my heart. A rusty bridge. A chopped down evergreen. A discarded can of Mountain Dew. It turned out my heart was everywhere that winter month.

We stayed with Howard's aunt in Flushing, and every night we would go to the local bar and take pictures of ourselves scribbling in our notebooks, our faces illuminated by the neon jukebox. It was at that bar that we met a 25-year-old Venezuelan furniture salesman named Jose. Howard and I thought Jose was the coolest. While we drank our rum and Coca-Cola's, Jose drank bloody caesars, something we considered very sophisticated, sort of like drinking a salad.

Howard explained his dilemma to Jose, and I explained mine. Howard had had cancer when he was 16 and was concerned he wouldn't ever be able to produce semen and have children. I explained that I had grown weary of being a virgin and really, really wanted to see naked chimichangas. Jose furrowed his brow and listened to our problems with concern. Then he said he was taking us to a whore house.

I cottoned to the idea of a whore house by telling myself that I was very old school, very Neil Simon, or Burt Reynolds, or something. It was probably how my father and his father before him did it. I imagined my grandfather had lost his virginity to a kind-hearted madam, who, after the deed, had cooked him a brisket.

Jose took us to an apartment above a fruit store in Spanish Harlem, where we were invited in by a small, older Latino man wearing a shoulder holster. Jose told us not to worry, that this is how things were done. We were seated on a couch facing an East Indian man and what appeared to be his two teenage sons. There were three women dressed in nighties who walked by carrying balled-up faded linen and punch bowl-sized metal basins with soapy sponges.

It was after seeing the basins that I realized I would never be able to pull this off. There was something too medicinal and matter-of-fact about the whole thing. Not only that, but I was terrified. Sex was one thing, but if I was going to be getting naked on a strange bed with sheets that were dubious, I at least wanted to be with someone who mildly liked me. And that, of course, is something impossible to gauge when the exchange of Canadian travelers cheques is involved.

I told Jose I would sit this one out. Howard, on the other hand, was raring to go. A woman came over to him and introduced herself as Crystal. Howard introduced himself as Mr. Cohenovsky, which was the name of our grade seven math teacher. Crystal took Howard by the hand and led him into a room.

Each person got 20 minutes. Howard remained in the room with Crystal for 40. The Indian man sitting opposite me kept pointing to his watch while smiling and winking. There's nothing that makes you think about dying a virgin more than sitting on the couch in a whore house waiting for your best friend to finish having sex. That couch just then felt like the loneliest place on earth.

As it turned out, Crystal saw Howard's scar, and they spent most of their time together talking about what it was like to have had cancer. Crystal had lost a brother to leukemia several years earlier. She told Howard that when her and her brother were kids, they poked toothpicks into bubble gum, which they ate like hors d'oeuvres. She told Howard that she missed her brother very much.

On the walk back to the subway, I lagged behind Howard, just watching him. Eventually we asked Howard how it was with Crystal, and he said that it was different than he thought it would be. And Jose told him he was being too emotional.

What I hadn't taken into account was that before you lose something-- in this case, the albatross of one's virginity-- you had to first find something to enable that loss. At 18, sort of by accident, I found Galeet. Her name meant, "little wave," and when we kissed, it was like a little wave of blood was sweeping through my chest. We kissed long and hard, our eyes wide open.

Galeet's face was always sad. I told her she had a frown that lit up a room. Galeet would be the first person I would ever sleep with, yet losing my virginity with her, even just after it happened, was something I can never remember. I could still recall what her breath smelled like after she had eaten chocolate, how she would almost cry when she saw little boys with big glasses. I remember a thousand other small things, too, yet our first time together, this thing that I waited forever to happen, to lose a virginity I had waited forever to lose, was completely and utterly lost to me.

I'm not sure I understand why this is. Maybe when you're coming towards it, it looks so big and all-eclipsing. It looks like the finish line. You imagine champagne, well wishers, certificates of merit. Then you reach it, and pass it, and you understand it's only the entry point to a lot of other worries, worries that prove to be much more immeasurable and complicated.

My fear of losing my virginity was nothing compared to my fear of losing Galeet. I could never fathom how she could love me, and so I tested her love all the time. "Let's say I smashed your car," I said.

"Then I'd kill you," she said.

"But you'd still love me?"

"I guess so," she said.

Before I met Galeet, I called myself a virgin. It was very clear and definite-- a virgin. Now there is no name for what I am. But I'm sort of partial to Leroy.

Thanks.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUDING]

Ira Glass

Jonathan Goldstein. He's the author of the novel, Lenny Bruce Is Dead. Jonathan's next book, which he's working on right now, is a rewrite of the bible.

[MUSIC - "TOUCH TO HAVE A CRUSH" BY OK GO]

[AUDIENCE APPLAUDING]

OK Go.

Act Two: Teacher Hit Me With A Ruler

Ira Glass

Act Two. Teacher Hit Me With a Ruler.

Can a song have skeletons in its closet? For this next act, Sarah Vowell decided to excavate the lost mongrel past of a patriotic song that I am sure you know. As songs go, it definitely had its wild party years before it settled down into the sort of thing that is played now at the White House, much like the current resident of the White House.

I have to say, I love the fact that that man was a drunk. That's one of my favorite things about him. Is that wrong? Shows character.

Please welcome Sarah Vowell.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUDING]

Sarah Vowell

At the memorial service at the National Cathedral on September 14, 2001, those gathered in the pews to mourn the more than 2,800 people who were murdered by terrorists three days before sang "The Battle Hymn of The Republic."

[MUSIC - "BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA TOUR BAND] Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord: He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored; He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword: His truth is marching on.

President Bush sang it. Ex-presidents Clinton, Carter, and Bush sang it. Watching it on television in New York City, I sang it. And across the sea at another service in another church, Queen Elizabeth sang it with tears in her English eyes, having sung the song 36 years earlier at the funeral of Winston Churchill, as Churchill himself had sung it along with FDR on the White House lawn in 1943.

Because that's when we sing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," at wars and funerals. So "The Battle Hymn" was doubly appropriate on September 14. It was a funeral, we were at war.

And yet there we were, we gathered Americans, her Majesty the queen, chanting this beloved battle cry at the terrorists of the world. And buried inside the melody of the song was the rotting corpse of an American terrorist. Here are the lyrics that used to go to that tune back in 1860, lyrics that honor the terrorist as a hero.

[MUSIC - "JOHN BROWN'S BODY" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA TOUR BAND] John brown's body lies moldering in the grave, John Brown's body lies moldering in the grave. John Brown's body lies moldering in the grave; his soul goes marching on.

I don't throw around the word terrorist lightly, but if it's John Brown-- Brown, a white man who hated slavery so much that even his friend, the famed abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass, wished Brown would shut up about it every now and then. Back in 1856, Brown and his men massacred five pro-slavery settlers from the south near Pottawatomie Creek, Kansas, dragging them from their homes as their wives and children looked on screaming. They hacked them up with knives, though Brown shot one man's mangled body in the head just to make certain he was dead for sure.

Then hoping to incite a slave uprising, Brown led a guerrilla attack on the Federal Arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia on October 16, 1859. 17 people lost their lives, including 10 of Brown's men, two of whom were his sons. Brown was executed on December 2, 1859.

Across the land, Brown's execution was either celebrated or mourned with the ringing church bells, depending on which side of the Mason Dixon Line one hung one's heart. In Concord, Massachusetts, Brown's friends, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, held a service in which Henry David Thoreau called Brown a crucified hero. Thoreau was so excited about Brown's martyrdom to the abolitionist cause, that he cheered that Brown's death gave people who were contemplating suicide, quote, "something to live for," exclamation point. And, as Lincoln puts it in his second inaugural, "the war came."

Then John Brown got a song of his own, sort of. Like every turn in this story, the song "John Brown's Body" is an accident of history. What happened was Union soldiers-- the 12th Massachusetts Regiment-- were stationed at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. As they went about their duties, the soldiers sang. One of their favorites was this Methodist hymn:

[MUSIC - "SAY, BROTHERS, WON'T YOU MEET US" BY JON LANGFORD] Say, brother, will you meet us on Canaan's happy shore?

There was a singing quartet in residence at the fort: Sergeant Charles Edgerly, Sergeant Newton J. Purnette, Sergeant James Jenkins, and Sergeant John Brown. One day in December of 1859, news arrived at the fort about the famous abolitionist. John Brown is dead. Some smart alec, thinking of his singing comrade Sergeant John Brown, is said to have replied, "but he still goes marching around."

A soldier named Henry Howgreen reportedly turned this wise crack into the first verse of the song about his comrade, "John Brown's body lies moldering in the grave, his soul goes marching on." A soldier who played the organ set it to the music of "Say, Brothers, Won't You Meet Us." So the song was a joke, joshing among soldiers, the sort of ribbing a sergeant in today's army might get if he had the misfortune of being named Uday Hussein.

"John Brown's Body" became the regiment's marching song. They sang in public for the first time, here in Boston on State Street, on July 18, 1861. After that, they sang it marching down Broadway in New York City. They sang it so often they became known as The Hallelujah Regiment. On March 1, 1862, they sang in Virginia on the very spot the abolitionist John Brown was hanged.

Three months later, Sergeant John Brown drowned while crossing the Shenandoah River on his way to battle. Heartbroken, The Hallelujah Regiment never sang "John Brown's Body" again. But by that time, they were the only ones in the Union Army not singing it. Northern soldiers would sing it on parade, marching from battle to battle, sitting around camp fires at night. And since no one had ever heard of Sergeant Brown, every soldier who sang the song thought he was paying tribute to the famed abolitionist.

Lyrics kept getting added on, including one doozy of a stanza about the president of the confederacy.

[MUSIC - "JOHN BROWN'S BODY" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA TOUR BAND] We'll hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree, we'll hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree. We'll hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree; as we go marching on.

In November of 1861, some white abolitionists from Boston, including Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Gridley Howe, and their minister Reverend James F. Clark, were touring a Union army base on the outskirts of the nation's capital. They heard some soldiers singing about John Brown's body "moldering in the grave." Reverend Clark turned to Mrs. Howe and wondered if she might like to write new, more uplifting lyrics to that fine melody of "John Brown's Body."

Not that Julia Ward Howe had a problem with John Brown. She had even hosted Brown at dinner in her home on one of his trips to Massachusetts, trying to drum up money he could use smiting the slave mongers. Basically, abolitionist pledge drive.

You are the public in public hanging.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER]

Julia Ward Howe would recall of the morning she wrote new lyrics that she had "the feeling that something of importance had happened to me." Back home in Boston, she gave the poem to her neighbor, James T. Fields, editor of the Atlantic Monthly. He paid Howe $4.00, gave her poem the title, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," and published it in the February 1862 issue. "The Battle Hymn" became a huge hit. Who knew the Atlantic Monthly was the TRL of its day?

Soldiers and citizens alike couldn't stop singing it. When Abraham Lincoln heard it at a rally, it is said that his eyes filled with tears and he yelled, "sing it again."

Sing it again.

[MUSIC - "THE BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA TOUR BAND] I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel: "As ye deal with my contemners, so with you my grace shall deal; let the hero born of woman crush the serpent with his heel, since God is marching on."

That line in the hymn about the hero born of woman, which is a shout-out to the Virgin Mary by way of William Shakespeare, takes on an extra meaning in light of Julia Ward Howe's biography. Though she was married for 34 years, raised six children, and is, in fact, the creator of Mother's Day, Julia how was not without ambivalence about domesticity. For example, she wrote a poem entitled "The Present is Dead. " On her honeymoon. In writing to her sister about what she called "the stupor of marriage and motherhood," Howe complained, "it has been like blindness, like death, like exile from all things beautiful and good."

So in "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," Howe reminds the nations that the Son of God had a human mom who did all the work. Hence, "let the hero born of woman crush the serpent with his heel," Howe is rubbing in the fact that even Jesus had to be potty trained.

Like a lot of your bigger hit songs, "The Battle Hymn" has been ripped off numerous times. Countless renditions have been sent to its tune, which is fair enough considering that Julia Ward Howe ripped off a song which was a rip off of a previous song. There was "Solidarity Forever," a union number from the IWW songbook.

[MUSIC - "SOLIDARITY FOREVER" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA TOUR BAND] When the union's inspiration through the workers' blood shall run, there can be no greater anywhere beneath the sun; yet what force on earth weaker than the feeble strength of one, for the union makes us strong.

There was "Glory Land," the official song for the 1994 World Cup, in which Darryl Hall, of and Oates fame, proclaimed to the soccer fans, "with passion rising high, you know that you can reach your goal."

[AUDIENCE GROANING]

I know.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHING]

And of course, that playground classic:

[MUSIC - "PLAYGROUND VERSION OF 'THE BATTLE HYMN'" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA BAND] Mine eyes have seen the glory of the burning of the school, we have tortured every teacher, we have broken every rule; we have marched unto the principal to tell him he's a fool, the school is burning down. The school is burning down.

[AUDIENCE CHEERING]

In the 1950s, around the time of the Korean War, something else happened to Julia Ward How's "Battle Hymn of the Republic." A word changed. The line "let us die to make men free" got change to "let us live to make man free." The new wording acknowledged that sometimes war isn't always the answer. Plus, less of a downer.

And through the years, a civil war of sorts has broken out between those who would die and those who would live. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir sings "live" on their 1959 Grammy Award-winning recording of the song. Joan Baez, leading a sing-along at a black college in Birmingham in 1962, went with the traditional "die."

In my opinion, die is the way to go. When you get rid of the word, "die," you erase the most moving idea in the song, that if Christ died for us, we should be willing to die for each other. Why give that up? This the one clear-cut case where you can ask yourself, "what would Jesus do," and you know the answer. What would Jesus do? Die.

And, of course, people disagree about the wording. We disagree about everything else in this country. And when we sing the song today, I think we even disagree about who the serpents are that our heels should crush. Some of us see our enemies abroad, some see them at home, some of us are still mad at France. And that's the way it's been with this song all through its history. It gets adapted for one use, than another. The melody is so powerful, the words so strong, you feel like you really would lay down your life for a just cause. Of your choosing.

When we sing "The Battle Hymn"-- and I say we because that is how the song is traditionally performed at public events, as a sing-along in which a group of citizens turn themselves into a choir-- we sing about taking action, about marching on, about doing something. And this is the best part about singing "The Battle Hymn:" you're not standing there alone doing something, you're part of something. The song starts off with "mine eyes," and "I have seen," and by the end it's "you and me" and "let us die" or "let us live," whatever-- "us" being the point. We're all in it together, if only for the length of the song.

Ira Glass

Sarah Vowell. She's the author of several books, including The Partly Cloudy Patriot.

Word about the band that's here in the stage. On this tour, we have the band OK Go. And we have this bad, headed by the seme-legendary Jon Langford of the Mekons in the Waco Brothers. A while back, John did a story with us and producer Starlee Kine on our staff in our show about the classified ads, we he put together an entire band from the musicians classifieds. And he's brought two of those musicians from that story with him here on the tour. On the far end you'll see Eric Muller on the theremin. Eric used to work for a company that made parts for the railroad. And on this end is Nathan Swanson, who still works part time for Home Depot, playing electric violin and mandolin. Alan on bass and Dan on drums, they're old pros.

[MUSIC - "HELL'S ROOF" BY JON LANGFORD AND THE LOST IN AMERICA TOUR BAND]

That was great.

Coming up, scraps of paper, personal letters, handmade signs, all discarded and then found. Maybe there's something of yours in there. You'll find out in a minute. From Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International when our program continues.

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Each week, of course, we choose theme, bring you a variety of different kinds of stories on that theme. Today's program, taped on the road in Boston, Portland, Oregon, Denver, Chicago, and Washington DC: Lost in America. Stories of people who are lost, words that are lost, things that are lost, and, now and again, found.

Act Three: I Found Your Letter

Ira Glass

We've arrived at Act Three of our program. Act Three: I Found Your Letter.

You know when you're walking down the street and you spot some random piece of paper floating around-- a page from a letter, a shopping list with a note on it, some kid's paper from class-- do you pick it up? Do you read it? Me? Very nosy, yes.

As writing goes, these pieces of paper, they're little writing orphans, cut off from their original life, cut off from everything that gave them meaning. But still there with a lot on their minds and a lot to say.

A few years back, Davy Rothbart decided that somebody, somewhere should do a magazine that was made up entirely of this kind of writing. And then through sheer force of will, he became that somebody and created Found Magazine. Now, people all over the country send him this stuff. He's going to come out and read some of this writing that has been discarded and misplaced, lost by its original owners.

Please welcome Davy Rothbart.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

Davy Rothbart

Everyone can find stuff. And I want to give you just a sense of some of the stuff that people are finding and sending in to us. This right here is a note that was found in LA.

And it says, "Jesse, I did not take anything. I know there's no convincing you once you've made up your mind. And although I cannot offer you any other explanation as to what happened to it, that doesn't mean I did it. How could I have? You say your car was locked and Katie had the keys.

Anyway, I don't need to take something of yours when I could get my own. It doesn't make sense. But here's a replacement, because I can't stand when you think I've wronged you. Mom."

[AUDIENCE LAUGHING]

The authors of some of these notes, they don't always paint themselves in the best light, you know? Sometimes they're going fine, fine, and they just skewer themselves at the end. And this is one that was found in Tacoma, Washington.

And at the top, OK, it just says, "what kind of relationship do I want? How do I see myself in it? I'm nurturing, I'm relied upon, I'm getting my ya-yas." But then down here it says, "what I hate about women: they're hard, impossible to please and satisfy. They talk a lot without saying much or being intimate. And they're self-involved and self-absorbed. I want them to be absorbed with me."

This one was found in Berkeley, California, actually on the front lawn of a fraternity house. And it was a whole book of letters back and forth from the elders of the house to the pledges, the young kids who are trying to get into the fraternity. So this is one of the notes that's from one of the elders to one of the young pledges named A.J.

And he says, "A.J., tonight's event was just a tradition of the house. It was not gay. Even though you had to pull down your pants, at least you didn't have to show it to all the actives, just your pledge master. Its meaning: to prove your manhood and that you are not a boy. But none of us are gay. Aside from all this, I want to know that I've seen some improvement out of you since your first pledge. Keep up the effort and have a positive attitude of things. I tell ya, it's all worth it once you've crossed. Take my word for it. Just hang in there, OK?

Listen, I want you to have dinner with me when you're free someday. It's a great chance for you to get to know me better and for me to answer questions you may have, all right? Aaron."

And so many of the notes, as I read through them when they come in the mail every day that people are finding, they deal with love and relationships, you know? And one of the favorite notes that I've ever found myself is this note I found in Chicago on my windshield. I came out of my friend's apartment late one night. It had snowed a little bit. And you know, with like a thin layer of snow, every car looks a little bit the same. And my name's Davy, but there's a note on my windshield that was addressed to Marco.

And it said, "Marco, I freakin' hate you. You said you had to work? Then why is your car here at her place? You're a freakin' liar. I hate you, I freakin' hate you. Crystal. P.S. Page me later?"

And then this one just came in last week from-- it was found in North Carolina. And it says, "Dear Will, the longer I think about what I'm doing, the sicker I feel. Will, I'm sorry, but I don't think we should continue to have a relationship together. At least not as a couple. I love you, but things have not been the same since we found out that we were related."

[AUDIENCE LAUGHING]

My little brother, Peter, he is the best finder I know. He amazes me with what he brings home. And this is one he found when he was visiting me in Chicago. And it's written in like a kid's handwriting. It looks like maybe a 12-year-old kid. It says, "To cashier, will you please sell my son one pack of Newport Lights." Ah, that trick. "Thank you for your help." On there's just this scrawled, adult-looking signature.

And then this one my brother found pinned under the back tire of his bicycle. And it's this handsome looking sign. Someone spent a good deal of time putting this thing together.

It says, "After leaving the building please lock this door. It will prevent unauthorized people from entering the building and defecating in the washing machine. Many thanks."

And when you send your finds in, I ask that you name your finds. And also that you write one line, you know, a sense of response or interpretation to it. About this one, my brother wrote, he says, "Note that those who are authorized to defecate in the washing machine will be given a key for entry."

And yeah, I applaud for whoever made that sign, but also for my brother, who just picked it up off the ground. And I asked him, you know, "how do you do it? What's your secret?" My brother says that it's been scientifically calculated-- by him-- that one in five, 20%, of all finds are gems of finds. So that means if you pick one thing up a day, that every week you'll have a real jewel of a find.

Let's read this one here. This is from Erie, Pennsylvania. And it's a note, a kid writing a letter to his dad.

It says, "Hi, Dad. What's up? Not much here. Just working to save money. I'm working at Old Country Buffet starting at $6.50 an hour cooking. Dad, are there any cooking jobs down there? Let me know when you write me back. I gave Cleav your letter, OK? Without Mom knowing, OK?

I can't wait to come down there. Erie sucks bad. There ain't nothing to do. Too cold. The weather sucks, too. Dad, I drink, too. Beer. Budweiser. But I don't drink a lot. And I do a little drugs, too. I smoke joints. And I got a bowl that's cool. I'll let you see it, OK? I talked to Grandma. She said she's going to send you a letter and some money.

Dad, I don't know if Cleav or Beth is coming down, but I'll talk to them and see. If not, it will be just me only.

Dad, you're going to rent a mobile home. That's cheap. $100 a week. That's cheap. Dad, try and see if there's any apartments for rent and let me know how much, OK? Dad, I'm going to take a Greyhound because it's cheap-- only $49-- but I'll call you ahead of time. Dad, all the money I'm saving from working at my job and my income tax check, I should have a lot, OK? With the money, we should be able to get a place for us, OK?

Dad, I can't wait to come down there pretty soon."

Turn over.

"Dad, I'm a cook, and I can cook us some [BLEEP] up. Cook some meals up for us, get a grill and cook on that. Also, I got a lot of CDs, like AC/DC, Led Zeppelin, Metallica, Pink Floyd, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Judas Priest, Black Sabbath, and all that. We can jam out and have lots of fun.

Ira Glass

Davy Rothbart. You can go to his magazine's website, foundmagazine.com.

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program was produced today by Julie Snyder, Diane Cook, Todd Bachmann, me, with our other producers, Alex Blumberg, Wendy Dorr, and Starlee Kine. Production help from Katie O'Dunn. Engineering for our show in Boston by Miles Smith. In DC, Jonathan Cherry and Big Mo Recording. In Portland, John Frazy. In Chicago, Mary Gaffney. Our March guru, Jorge Just.

Thanks to Adam Beckman. Ken Sleuter mixed one of our bands. Brand Cutsman the other. Thanks also to Robbie Willard. Thanks to the public radio stations who have been our hosts and presenters in the five cities. WBUR in Boston. WAMU, 88.5 FM in DC. Oregon Public Broadcasting in Portland. Colorado Public Radio in Denver. And Chicago Public Radio in our hometown.

Special thanks today to our bands in all of our cities but DC. Dan Massey on drums, Alen Doughty on bass, Eric Muller on theremin, Nathan Swanson on violin and mandolin, plus Pat Brennan on piano and John Rice on guitar, and the great Jon Langford on guitar and vocals. In DC.

OK Go is Damian Kulash on vocals, Tim Nordwind on bass, Andrew Duncan on guitar, Don Konopka on drums and Burleigh Seaver on keyboard.

Our web site, www.thisamericanlife.org. This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

WBEZ management oversight by Mr. Torey Malatia, who begs, begs you,

Jonathan Goldstein

Quit tickling me. I have to make this an early night.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

[FUNDING CREDITS]

You can download audio of our show at audible.com/thisamericanlife, where they have public radio programs, best selling books, even the New York Times, all at audible.com.

Announcer

PRI. Public Radio International.