875: I Hate Mysteries

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue: Prologue

Ike Sriskandarajah

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ike Sriskandarajah filling in for Ira Glass.

Maria

Calm bodies, calm voices, calm minds.

Ike Sriskandarajah

It's calm, for now, in the second grade classroom in Cold Spring, New York. There are about a dozen kids sitting close around a rug, knees touching.

Maria

Let's listen to the sound of the bell.

[BELL DINGS]

Ike Sriskandarajah

These kids are getting ready for a very particular lesson. It's one that I heard about from my coworker, Nadia. I asked my wife, who's a teacher, and she knew about it, too. And a friend of mine says he still remembers this lesson from when he was in third grade. It stuck with him. And I wanted to see this rite of passage play out for myself.

Maria

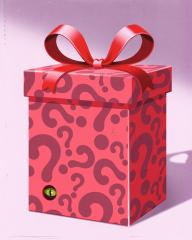

All right, so the game we're going to play today is called What's in the Box? Have you played this game before?

Students

Yes.

Ike Sriskandarajah

It's a guessing game that's kind of famous here. Ms. Maria, the director of the Manitou School, holds up a white cardboard box about the size of a shoebox.

Maria

So I have put something in this box, and you can't break it by shaking it. So you can shake it. You can move it. And we're going to pass the box around, and you're going to tell me what you think is in the box, OK?

Ike Sriskandarajah

The kids seem amused. They want to try. She passes the box to the child on her left. The kid shakes it a little.

[RATTLING]

Student 1

Uh, LEGOs.

Student 2

Uh, a stapler?

Maria

Hmm.

Student 3

Uh, maybe marbles and-- marbles and balls.

Maria

Marbles and balls. Hmm.

Ike Sriskandarajah

As the box makes it around the 13 students, strategies start to emerge. One thoughtful little girl in purple glasses and snow boots shakes it real hard.

[RATTLING]

That doesn't get her any closer. The next time around, she takes off her own beaded necklace, shakes that close to her ears. Then she closes her eyes and shakes the box.

Student 4

Yeah, they're both this-- they're kind of-- OK, definitely not what I thought.

Ike Sriskandarajah

The rattles are different. Nobody has gotten it. Feels like it's time to bring in a dedicated professional in the answers-getting business, and the kids allow it.

Ike Sriskandarajah

Can I shake the box? You guys don't mind?

So I pick up the box. And they're right. It's about the weight of a toy, maybe the size of a fist or two, with smaller things rattling inside that object. Eureka!

Ike Sriskandarajah

OK, um, is it, like, a toy car with gumballs in it?

Maria

That's a really good guess.

Ike Sriskandarajah

But not good enough. Three times around the class, and nobody has guessed it. At this point, the kids are done. They're ready to find out. And that's when Ms. Maria does something the kids do not see coming.

Maria

All right. Cool. Well, thank you for playing.

Student 5

Can you show it to us?

Maria

I didn't say I was going to tell you what it was.

Student 5

What? Please!

Maria

'Cause the game is about guessing. It's not about knowing.

Ike Sriskandarajah

She doesn't tell them. She was never going to. Ms. Maria takes the box away. And the kids are stunned. No more tries? No answer? That's it? They're not sure what to make of it.

Now, if hearing this makes you mad, if you're thinking, hey, that is not what school is about-- school's about finding answers to your questions-- Ms. Maria agrees. But she thinks this is important to learn, too. She wants them to learn how to endure the discomfort of not knowing. She's trying to prepare these kids for life, and that's the case she makes to them.

Maria

And sometimes we all have things that we can't know sometimes because Ms. Maria won't open the box, but more often because it's just impossible to know. Like, your parents can't tell you certain things, or you can't get into somebody else's head, or you just can't know the reason for why something happened. So learning to live with that discomfort of not knowing is a really important thing. And that's part of what we were practicing here today.

Ike Sriskandarajah

Sure, but the box is right there. It's just behind Ms. Maria on the floor. The answer is inside, just like all the other answers that powerful forces in our world are withholding from us. These kids and this journalist aren't having it. Ms. Maria's worthy lesson is overcome by a much stronger human impulse-- the desire to know what's in the box.

Student 6

We want to know what it is!

Maria

Is it important, what's in the box?

Students

Yes!

Student 7

Otherwise it'll keep us wondering, and I don't like mysteries!

Maria

Why would you keep wondering?

Student 7

Because I want-- 'cause I would want to know what it is.

Student 8

No, we don't want. We need!

Maria

Oh, you need to know what it is.

Student 8

Need!

Students

Yeah!

Student 8

We need to know!

Student 9

And I get sick when I'm wondering.

Maria

You get sick?

Student 10

And I don't like surprises.

Student 11

I'm allergic to wondering. I'm allergic to wondering!

Ike Sriskandarajah

Ms. Maria tries to bring the class back from the brink of anaphylactic shock. They talk about techniques to deal with the discomfort. They stand up and try to shake their body loose of the tension.

Maria

Do you feel better--

Students

No.

Maria

--having shaken it off like a duck? No?

Students

No.

Maria

No?

Student 12

We feel better when you open the box!

Maria

OK.

Ike Sriskandarajah

Apparently, this is not an uncommon reaction. Ms. Maria told me years ago, she remembers when an entire class worked together to steal the box. The most trustworthy kids told her there was a plumbing emergency in the girls' bathroom, while another classmate snuck into the office Ocean's Eleven style. The heist was foiled, and then the box was moved to a secure location. And just earlier today, Ms. Maria was showing some of the teachers the mystery box before class. They made their guesses. And then she caught one of them trying to sneak a peek. The mystery, it can get to you not only if you're seven, but especially if you're seven. These kids, they see the future, an inscrutable world of infinite, unanswerable questions, and they say, no.

Student 13

You're going to leave us wondering for the rest of our lives!

Maria

For the rest of your life?

Student 13

Yes.

Students

(CHANTING) What is it? What is it? What is it? What is it?

Ike Sriskandarajah

Ms. Maria is just leading this lesson. The regular classroom teacher wants to have kids who aren't freaking out and distracted the rest of the day. She would love this to end. So in a shocking turn of events, Ms. Maria caves to the mystery.

Maria

You're going to feel better when I open the box?

Students

Yes.

Maria

OK. Here we go. This is the big reveal.

Ike Sriskandarajah

She opens the box and shows that kids what's inside.

[SHOUTING]

Teacher

Oh, my gosh. I would never have guessed.

Ike Sriskandarajah

But you? You can wait a little longer, right? Today, we'll hear people who stare at the giant question mark and plunge themselves deep into the unknown. What lies on the other side? You want to know? Do you really want to know what's in the box? Stay with us.

Act One: The Masta Blasta Digging Up Mt. Shasta, That Hole is Deep Cuz It Hasta (Be)

Ike Sriskandarajah

It's This American Life. Today's show, I Hate Mysteries. Act One, The Masta Blasta Digging Up Mount Shasta. That Hole is Deep 'Cause it Hasta Be.

A while back, filmmaker Elijah Sullivan decided he was going to get to the bottom of a very strange event that happened in his hometown. Timber workers going through a national forest found an incredibly deep hole in the ground. Nobody could tell who had dug it or why or what they were looking for. Everyone in town had a theory, and some of those theories were really wild.

Elijah could not stop thinking about this hole. He'd been working on a documentary about it for about nine years, when someone got in touch with him who claimed to be one of the diggers. Here's Elijah.

Elijah Sullivan

His name was Brett. He said that depending on certain circumstances, like the statute of limitations, he was open to talking. He'd told pieces of the story before over beers. So I got him a beer, an old one from the fridge.

Elijah Sullivan

Does that still taste good? It's been in my fridge for three years.

Brett

I'm not afraid of a skunky beer, man.

Elijah Sullivan

OK. Do you feel like launching into the story now?

Brett

Yeah. Yeah.

Elijah Sullivan

You want to start?

Brett

Yes, sir. All right, ready?

Elijah Sullivan

Yes.

Brett

All right.

[CLACK]

Elijah Sullivan

For the next two hours or so, over a skunky beer, Brett told me his tale, the story I'd been waiting so long to hear, the story of the hole. It started in 2009, right after the Great Recession. Brett was just out of high school, living in Northern California and looking for work. As a kid, he said, he had never really fit in and had been kind of heading down a bad path.

But he loved the outdoors. He'd worked for the California Conservation Corps and later trained to fight forest fires, which he was excited about, but his crew wasn't getting called up. He spent months looking for other jobs. Then he came across this listing on a message board.

Brett

And I looked, and there was a job opening. And it said, building a fence line in Mount Shasta. So I called the number, and a guy answers. And he goes, how old are you? And I tell him. I'm like, I'm like 19. He's like, oosh. Do you have your own tools, your own gear, gloves, boots? And I'm like, yeah. He goes, how fast can you be in Mount Shasta? And I'm like, well, I'm in Redding. I can make it in, like, 45 minutes, around there.

And he says, OK, go to this hotel, and a guy is going to meet you in the lobby. He'll give you a room. You'll meet up with the work crew in the morning and then go out and build this fence. And I'm like, all right, cool. Sounds good. So I put the last $40 I had to my name in my gas tank and drove my truck up to Mount Shasta.

Elijah Sullivan

Mount Shasta is this 14,000-foot, snow-capped stratovolcano near the Oregon border, with a small town nestled at its base. I've lived there basically my whole life. Brett arrived in the evening, pulling into a hotel in Mount Shasta City, right off of the freeway. As promised, there was a guy waiting for him. He seemed like the foreman of a crew.

Brett

And I think he was-- he had to have been around late 20s maybe, like 27, younger guy, in shape, covered in tattoos, very forward, very disciplined. And he just walked out, and he was wearing basketball shorts and flip-flops. And he goes, here's your key. This is your room. Meet the guys in the parking lot at this time in the morning. And I'm like, OK.

Elijah Sullivan

Finally, a job. Not only a job, but it paid well, and it got him out of Redding. They even gave him his own hotel room and a per diem.

Brett

The next morning, I wake up. There's a van. And everyone's got milk jugs of water and stuff like that. And I meet up with them, and they're all bullshitting. I can tell they've been doing it for a little while, but I didn't know how long. And so I get in this van with these complete strangers, and we start driving up towards the mountain. And I remember driving backroads. And then we pull over in the middle of nowhere, and there's a trail at the tree line. And I get out, and we start walking. And I'm like, where are we going? We're building a fence.

So we start walking and walking and walking. And eventually I'm like, all right, guys, where's the fence? And I get laughed at. And I'm like, what's going on? Like, come on. And they're like, they told you a fence? And I'm like, yeah, yeah, I can string a fence. And they go, that's funny. Yeah, I got told I was putting a barn up. And another guy said something else, and another guy said something else. And I'm like, OK, now I'm far from home. I'm walking what feels like a couple miles down this trail into the wilderness with guys I don't know. And they're laughing at me, telling me I've been lied to about why I'm here. And that's when we got up on the hole.

Elijah Sullivan

The hole. The mouth of it was enormous, at least 10 by 12 feet. And it was deep, like a vertical mineshaft without any wooden beams holding it up, just sheer walls. Off to one side was a huge pile of dirt. Above, there was a steel cable with a pulley strung between trees. A few feet down was a boulder the size of a small car sitting on a ledge, and then a ladder leading down into the darkness.

Brett

I remember looking in the hole, and everybody's getting ready. And I'm asking, what's going on? And they're like, we're digging. And I'm like, for what? And he's like, well, we don't exactly know. We were told if we found something weird, that we pull it out, and we were going to give it to Joseph.

Elijah Sullivan

Joseph was the guy running everything. Brett said he looked like a flatlander, meaning not from the mountains.

Brett

And he completely stood out. 'Cause all of us were blue collar workers, and we're in boots, jeans, cut-up shirts. And he was in a full suit, had dress shoes, full suit, up to the nines. And he walked that trail with us every single day, completely dressed.

Elijah Sullivan

Somehow, all this weirdness-- the guy in the suit, being lied to, digging for something mysterious-- Brett says he just kind of went with it, maybe because he was surrounded by adults who had accepted it. He told me he didn't want to be the young guy asking too many questions. And also, he needed the money.

Workers disappeared down the hole to work in pairs. They used pickaxes to loosen dirt and fill 5-gallon buckets. Brett was told to stand at the edge of the hole and to hoist the buckets up. A plunge into the hole seemed likely to prove fatal, so Brett tethered himself to a tree, just in case. The simplicity of the work was satisfying, even validating. He'd been on trail crews before, so he knew more about this kind of work than most guys. For example, before Brett got there, the crew had run into a boulder in the hole and hadn't known what to do.

Brett

The main boulder, they had dug around at one point. And I remember asking, why didn't you go through it? And them looking at me kind of weird, and they're like, well, how would we go through it? We've tried. I'm like, well, how did you try? Well, we brought a battery-powered jackhammer up here, and I'm like, how'd you-- in the wheelbarrows and carrying. And I'm like, no, no, no, no. You drill into it using leaves and feathers, and you split the rock in multiple sections and it'll break. And once his eyes lit up, it was like, OK, this young kid might know a few things.

Elijah Sullivan

Anytime anyone had an idea to improve their digging operation, Joseph, the guy in the suit running things, would head down the trail back into town for supplies. He had a credit card, which Brett called the magic card.

Brett

Joseph was like, I've been given this card. Whatever we need to make this happen, I will swipe it. And he was swiping that card, and infinite money to make this happen.

Elijah Sullivan

Brett quickly fell into a routine. He would ride up the mountain every morning, tie himself to the tree, pull buckets all day, then go back to his hotel. The others would go to the bar or to get food, and Brett would just go to the gas station or back to his room. Then they would start again in the morning. Week after week, with every bucket he pulled, he watched the hole get deeper. One day, it was finally Brett's turn to work in the hole.

Brett

They kept that shaft very square. I mean, you could look up at the top of the hole and see the iron veins when the sun would come over the top. It was beautiful. When the sun would come over and the light would shine into the hole, you could see iron veins all the way down the sides.

Elijah Sullivan

Maybe the adventure made it easier not to think about the bigger questions, like what they were doing there. Speaking up might have meant going back to Redding. At least he was outside.

Brett

Like, nature's my thing. I'm peaceful. I'm calm. I'm happy. And maybe that was how I justified part of it. It was good for me to be up on that mountain every day. And maybe that's what-- it wasn't just being naive. It was overlooking circumstances, because I was out there every day.

Going up and down the trail, it was like the Seven Dwarves. We were laughing, tools over our shoulders, jugs of water. They had milk jugs. I had this little Smartwater bottle that I'd carry with me, and laughing. It was constant. Like, somebody would say something down the line. You'd be walking and turn your head back, and get back in the conversation, get up there.

And I started making friends a little bit with people. There were a couple guys in the crew that were cool to me, kind of took me under the wing-- cooler, older guys. And for me, at that time, trying to find my place in the world, and a bunch of older guys being like, this kid's the kid-- and I was like, I'm in, let's do it. That praise, at that time in my life, went a long ways for me. So that smoothed over the edges quite a bit in the beginning. But it didn't last forever.

Elijah Sullivan

As the summer wore on, the adventure wore off. The deeper they went, the harder it was to dig. Sometimes the hole would fill up with bees. As it got deeper, they had to add things to reach the bottom. There was a rope to get into the hole, then a chain leading to two ladders tied together. Brett occasionally would help with the digging, but mostly, he was above ground, pulling the buckets up, which meant he had a bunch of time to be around Joseph.

Brett

I had a feeling that Joseph was not the one calling the shots. He was the representative for somebody. And I would ask questions a little bit on who was running this, and very circular conversation-- was not getting a lot of answers. Joseph used to get these phone calls. We would go a couple days without finding anything, and then he'd get a call on his cell phone, an old flip phone back then. And you could just tell his demeanor would change.

The phone would ring. He'd pull the phone out, take a breath, walk like 10 feet out in the woods, and he'd have this phone call. And you'd see him in the bushes. He's not on the trail. He's standing in bushes, in nice leather flat shoes and in a suit, kind of pacing around in circles a little bit, kicking the ground, and lots of nodding. And he'd come back and take a deep breath and then, OK, guys, let's keep going. It's like, we haven't stopped. So there was definitely some type of driving force that he was getting from the organization he worked with. It was almost a "don't come back unless you find it."

And we started getting worried, especially when we knew how important this thing that we didn't know what it was, was to them, that what happens when we find it? When the older guys started getting scared, that's when it started coming out in me. Because there was moments where Joseph wasn't necessarily totally with us walking up the trail, and that's when we started having these conversations.

Elijah Sullivan

There had been so much time to think, to imagine where this was going, what they were doing, why they were doing it. Brett wondered if the people funding it had some mining license that was about to expire. That would explain why they were in a rush, but not all the other weirdness.

Brett

Like, whatever we're doing is shady, at least. I don't even know if the word "illegal" was thrown around, but this is shady. And that's when I found out a couple of guys were like, look, I'm going to bring a gun up with me. I remember one of them was like, dude, if we find it, what if they kick us in the hole?

I'm standing next to that hole all day long. There's already guys in it. There's a gigantic boulder on the edge. I think it was a chain was holding it in place, maybe. All of us were in the hole, around the hole. It would have been very easy to push us in.

Elijah Sullivan

Brett started to think about bailing. I asked Brett why he hadn't before. Part of it was that he just wanted to know what they were digging for, the answer to the mystery. Now he wasn't so sure he wanted to know. Anytime they found anything that might be something, it was carefully inspected by a guy named Cokey.

Brett said Cokey was an old Navy vet, more of a blue collar guy like the other workers, and reminded Brett of his grandfather. Everything they found in the hole went to Cokey. And at some point, they started finding these rocks, kind of sizable, maybe twice as big as a basketball. And they all looked similar. Cokey would crack them open. They weren't allowed to look.

Brett

And then towards the end, it was like we were finding more of it. And then, [SIGHS] I can't remember if it was mostly one day we pulled a bunch out, but I just remember pulling buckets and hearing dudes yell and then trying to get them out, handing them off. They get pulled over to that little platform built up by the dirt we had pulled out. And Cokey had turned his back to us. We kind of looked away. He split a couple of them.

Elijah Sullivan

Brett says, for the first time, Joseph and Cokey's faces lit up.

Brett

And I think-- I think they sent us home. And we never called it early.

Elijah Sullivan

Brett went back to his hotel.

What just happened?

Brett

I thought I was coming back the next day. I just was like, if we found what they're looking for, why are we leaving? So that's why I went back to my hotel room, laying in bed, really like, what's going on? Have I got myself into something? And that's when I got the phone call in the middle of the night.

Elijah Sullivan

It was the crew lead. He said he would give Brett $200 to drive up the mountain with him and gather all the rocks they had found in the hole, just the two of them right now. Brett agreed. He told me it was stupid of him to go, but he thought, let's get this done, and then the job will be over with.

Brett

We loaded up my truck and went up the mountain in the middle of the night. It would have been around midnight. I parked my truck at the bottom. We busted out one Rubbermaid trash can. And he looked at me, and he was like, this is what we're going to do. We're going to put this trash can in between us. We're going to take our belts off, and we're going to loop it through the handles. And each one of us is going to put our belt on our shoulder, and we'll take as many down as we can.

We hiked up there, and that's what we did. We went to the pile of rocks that were ranging from here to about here, and we'd put as many in there as we could. And we'd do the shoulder test. Pick it up if we can get it off the ground. And if we could, it was like, all right, buddy, let's go. And we went down the trail. Loaded my truck, came back up, did it again, over and over and over again, aching. And we kept a pace. And we made lap after lap, I mean, just bleeding sweat, coming down that mountain.

And by the time we were done, my back of my truck was full. I had an old '89 Chevy. And I flattened my leafs and I blew out my brakes on the way down. I barely made it down that mountain without losing control at the bottom.

Elijah Sullivan

The two of them drove the rocks to a rental storage place. Joseph was there waiting. So was a U-Haul truck.

Brett

Then it was really solidified that this is done. Because when they cracked the back, and I saw they had wooden-framed the inside for one little cradle for each rock-- and they were ready to go. I don't remember the drivers getting out. I don't know who was driving them. And we picked those rocks up. We put them in there.

And Joseph shook my hand, and he was happy. He was happy. The stress was off. Whatever stress was on him, he had accomplished it. And then I had heard-- I either overheard or he told me that they're going to Florida. And they left.

Elijah Sullivan

Brett didn't realize until an hour or two later that they hadn't paid him the $200.

Later that summer, timber workers stumbled across the hole while marking trees. It was in a national forest, and it's illegal to dig without a permit. The hole looked to be about 60 feet deep. I spoke to one ranger who said it was the damnedest thing he had ever seen in his Forest Service career.

The Mount Shasta Herald ran an article in October-- "US Forest Service investigating hole on Mount Shasta." The article had a photo of the hole. At the bottom was Brett's bottle of Smartwater. Gawkers kept gathering to look at the hole, so the Forest Service filled it back in. By the time I saw the spot a few years later, the trail had faded, but the trees still had scars from the cable. And there was a 5-gallon bucket lying around. Every time I visited, it was in a different spot. And one day, it was gone.

At the time, all we had was wild speculation. There were three plausible theories. The first was gold. I heard rumors about an underground river of gold, maybe a treasure map purchased in a bar. But I talked to the geology instructor at the local community college who pointed out that Mount Shasta was actually a volcano, and volcanoes don't have gold in them, so that theory was out.

The second was Native American artifacts. Unfortunately, this is incredibly common in the US. I asked some state police officers and experts on investigating looters, but nobody had heard of looters digging 60 feet straight down. So the looting theory was out, too.

That leaves the third theory. It's something we locals discuss the most. But Brett isn't from here. He didn't hear about it until midway through the dig, when he went home for the weekend. He was drinking beer with some friends on their porch and telling them about the job he was doing on Mount Shasta.

Brett

And I started getting into the details of it, and everybody gets kind of quieter and quieter. And I hear this noise from above me because it was a multi-story. I think it was a two-story apartment complex. And I hear, oh, and then footsteps moving. And then I hear it running through one of the apartment complexes, coming down the stairs. And it was this really spun-out woman that came out holding a book.

So she goes, sorry, I've been listening to everything you've been saying, but this is what's going on. And she hands me this book about Mount Shasta and starts going through the pages and finds this chapter on Saint Germain. And she goes, do you know what this is? And I'm like, no. And she's like, OK. And I started reading it. And that's when it clicked.

Elijah Sullivan

The Count of Saint Germain was a real historical figure from the 1700s. Some people believed he was immortal. An American mining engineer named Guy Ballard claimed he met Saint Germain in 1930, here, on the mountain. Ballard said he was hiking, and Saint Germain appeared multiple times, once offering him a crystal cup filled with a clear, sparkling liquid. This encounter inspired Ballard and his wife, Edna, to found a New Age religion called The I AM Activity. That's two words, "I AM," all caps. Ballard died in 1939, but The I AM Activity still has members all over the world.

Around the same time Guy Ballard says he met Saint Germain, a book was published called Lemuria, Lost Continent of the Pacific. It had a chapter that claimed there was a hidden city under Mount Shasta, inhabited by some of the last remaining members of a sunken continent. People have been looking for the entrance of the city ever since.

The book is not related to Saint Germain, but added to the myth of the mountain. Not everyone comes to Mount Shasta for Lemuria or Saint Germain. Some are just looking for purpose or community. My parents were seekers. They moved us to Mount Shasta from Massachusetts when I was six. So to me, this made total sense, that the hole had something to do with all these stories.

Eventually, I tracked down and spoke to three other people who had helped dig the hole. One of them said they'd been paid by a believer in Saint Germain and described what they were looking for as gold plutonium. He said something about it being used to power Lemurian cities.

The other two diggers mentioned uranium. None of it made sense, but it always pointed back to the stories about the mountain. I did try to contact The I AM Activity a couple of times, but the person who answered the phone told me that my message probably wouldn't be returned. It wasn't.

After that last scary night on the mountain, Brett drove straight home to his mom's in Redding.

Brett

I just couldn't believe all this had happened. And then, plus, I hadn't slept. And I got back. I hadn't been telling my mom what I'd been doing. I told her I was working. And I remember I called my dad. My mom is a sweetheart, and she's always been the one that's let me run a little crazy, but has been like my stone.

And my dad is a lot like me. And I started telling him what I had been doing, and he got upset. And I remember that was the final thing where it was like-- when he was like, you cannot do stuff like that. You have to realize what you just did, and I'm very happy you're safe. But that could have gone very bad. And you can no longer go through life being naive like that.

And I was happy. I remember I picked up my skateboard, and I met with my friends and spent a week off-gassing, just letting all that go. And then once you're out of that mindset, you're not around those people, then you start realizing, what were we really doing? What did I let someone talk me into? Am I liable for anything?

And that's why it was really chilling when I got that phone call. I can't remember how long it was, so I'm trying to think. It was after the summer. And maybe it was around the fall. And I had a call came through that I didn't recognize the number and answered it, and I recognized the voice instantly. That stoic, man-of-few-words voice telling me, we're going back. And I remember being like, good luck, because I'm not going.

Elijah Sullivan

After that, Brett joined the military and rarely comes back to the area. Like many before him, he had come down from the mountain with a wild story. He still thinks about it.

Brett

There are times when I'm out elk hunting or something. I'm breaking brush off trail, and I'll see-- I'll come up over a hill, and you'll see a false summit or a gully in the ground or something like that. And you start seeing-- my brain will put shit together. When the landscape's just right and the sun hits, I'm on the right slope, and, yeah, things in the environment and the landscapes are piecing together, and I can picture it again. That'll be with me forever.

Elijah Sullivan

If you met Joseph again, do you have anything you'd want to say to him?

Brett

Man, I'd ask why. I'd take everything I just said, and I'm like, am I right? Is this what you were doing? Is this the motivation? Was it this church that is all the things, these little details that I put together from things you've said, things I've heard, things I saw? What weren't you telling me? And then the next thing is, what did we find? Because I saw it. It didn't seem like something that was worth doing what we did. Am I wrong?

Elijah Sullivan

I wondered about those things, too. A strange final footnote to this story is that the Forest Service did find the person they think is responsible for the hole. Their local Forest Service law enforcement officer, Carmen Kinch, told me she did a bunch of sleuthing and figured out what hotel the workers had been staying in, and from the hotel, the name of the person who had paid for the rooms. She said the person said they had been looking for gold and paid a fine, but couldn't give me the person's name.

And without a name, I haven't been able to find any court records, though I tried for years. These days, I'm not looking so hard anymore. I've had to accept that you just don't always get to the bottom of everything. Sometimes, when you open the box, inside, there's just another box.

Ike Sriskandarajah

Elijah Sullivan. His documentary is called The Hole Story. It's showing at film festivals, and he's looking for a distributor. Special thanks to Benjamin Bombard, who told us about the documentary.

When we were putting together today's show, we heard from lots of people who have mysteries in their lives that they can't get out of their head. And one of them came from Lauren Peterson, who read a story with a mystery in it that stuck with her.

Lauren Peterson

So for years, I have been plagued by a New York Times article by Katie Weaver-- whose writing I love-- where she went to a glitter factory and toured the glitter factory.

Ike Sriskandarajah

And while Katie was on this tour, the glitter factory spokesperson said, you'll never guess which industry buys the most glitter, and then wouldn't tell her. No matter how many times the reporter asked, the spokesperson said, we can never tell you.

Lauren Peterson

And for years, I have been desperate to know, who is this secret consumer of glitter? What could it possibly be?

Ike Sriskandarajah

You need to know.

Lauren Peterson

You need to know. And I think the piece came out around Christmas, I want to say. So this was also the number one topic of conversation among my family and extended family for that entire Christmas. Everything we thought of, it either didn't seem like it would be big enough, or there was no reason that they wouldn't want us to know. Like, if it was cosmetics, why couldn't they say that on the record? So it can't be that. But is it, like, why is your toothpaste so sparkly? Could it be-- is it the fluoride or is it glitter from the glitter factory?

Ike Sriskandarajah

Her wife thought it could be the US military. She'd heard they'd dropped metallic material from planes sometimes to scramble radar.

Ike Sriskandarajah

How many people were in on this?

Lauren Peterson

My mom is one of eight. So that's a big family on that side. We definitely talked about it. Plus, some friends. I have a group text where, every once in a while, one of us will put forward a new theory to this day. So I'd say we're looking at 20 people who I'm regularly bringing this up to. I once brought it up to someone who I was sitting next to on an airplane. I occasionally will just go back and look at the Reddit forums where people are trying to figure out the answer. What could it possibly be?

Ike Sriskandarajah

And what if I told you we have the answer?

Lauren Peterson

My jaw dropped. [LAUGHS] How did you find out?

Ike Sriskandarajah

Would you just open your phone and type in the word "glitter mystery"?

Lauren Peterson

Yes. Yes, I will-- and not for the first time, I might add. [LAUGHS] OK, when you google glitter mystery, the very first thing that comes up after the AI is, the mystery of the largest glitter purchaser has been solved. [LAUGHS]

Ike Sriskandarajah

The post is a link to a 2019 podcast that broke the news of the mystery buyer. There's a long Reddit discussion about the answer. But somehow, Lauren had never seen it. So I told her.

Ike Sriskandarajah

The largest buyer of glitter is boats.

Lauren Peterson

Boats?

Ike Sriskandarajah

Yeah, boats. They use it for their paint.

Lauren Peterson

Sparkly? I mean, I guess they are. Why don't they want us to know?

Ike Sriskandarajah

I don't--

Lauren Peterson

Why does it have to be a secret? They're not military-grade boats. They're just regular boats.

Ike Sriskandarajah

May I ask you, are you happy that you know?

Lauren Peterson

No. Such a disappointing answer. And I kind of wish I still thought that the US military was glitter bombing other nations. [LAUGHS]

Ike Sriskandarajah

Everything that glitters is not boat, but a lot of it is. Lauren was not the only person disappointed in the answer. On Reddit, there were even people who worked in the marine paint industry who knew they used lots of glitter, but they were also hoping the answer was something else. Mysteries are like that. Once you have the answer, the sparkle disappears.

The biggest glitter buyer was originally uncovered by the podcast Endless Thread. We reached out to Glitter X, the company profiled in the New York Times story. They declined to confirm if their biggest buyer is boats. They are still committed to the mystery.

Coming up, did we just become best friends, or am I being kidnapped? That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio, when our program continues.

All That Glitters

Ike Sriskandarajah

It's This American Life. I'm Ike Sriskandarajah, sitting in for Ira Glass. Today, I Hate Mysteries-- stories of people grappling with the unknown that's right in front of them. Act Two, Who Are the People in Your Neighborhood? The mystery that I want solved most urgently right now is, what happens when the full force of the federal government arrives on my block? I happen to live in a neighborhood in New York City that is half foreign-born.

Given the national tour of Border Patrol, ICE, and sometimes the National Guard, it seems like they could come here. They just closed their operation late last week in Chicago, Operation Midway Blitz. According to DHS, they arrested 5,000 people in the Chicago area. Immigration arrests didn't stop after that. They're just not at the rate they've been at in the past two months.

We can get some sense from videos on the news and social media about what happened in Chicago-- people dragged out of cars, chased into daycares, neighborhoods teargassed. But what is it really like to live in a neighborhood like that day to day? So we called one of our former colleagues, Michelle Navarro. She grew up on the southwest side of Chicago, a Mexican part of town. And she still lives there. Here's Michelle. She changed some of the names in this story.

Michelle Navarro

I've been getting this question a lot. Friends from out of state have been hitting me up, asking me, are you good? They want to know what it's like here. They want to know if the videos and the things they've read are how it's actually playing out.

I haven't known what to say. I had to go back through my phone to know what just happened, because it's been hard to remember. I've been scrolling back through my text messages, through the half-sentences I wrote in my Notes app, the videos I saved on my phone. I need them to remember my own life because I don't even know.

They launched Operation Midway Blitz in early September. That is when they started to bounce between neighborhoods-- Back of the Yards, Brighton Park, Gage Park, Little Village, Pilsen, Little Village, and Back of the Yards again. In little over a week, more than 500 people were detained. It was a free-for-all, a purge. There's no other way to describe it.

And when they take people, they vanish. They're out as a family at Millennium Park on a Sunday. They're waiting for the bus, taking the trash out, selling tamales. Then men in ski masks and mismatched tactical gear appear. And then they're gone.

My phone is a catalog, an archive of how we tried to keep living our lives. This is what I found. Scrolling back to the early days to when they started grabbing people from the street, there's a text confirming my nail appointment at Jessica's Nail Spa, Wednesday, September 17, 2025, 5:30 PM. See you soon, Michelle Navarro.

I remember that day. That weekend, I was hosting a party for my roommate's birthday. I'm used to being welcomed to the nail salon with laughter and loud Spanish love ballads. I'm a regular. They usually tease me. Let me guess-- red, square tip? But this time, when I approached the salon, and I pulled on the door to find it locked, I watched their heads lift in unison. I saw relief when they realized it was just me.

I know all the women who work here. We usually ask each other about work, about boyfriends, about family. This time, we didn't. We waited, as we always do now, to see who was going to bring it up first. It was them. They told me they think about it all day. They heard ICE was spotted in the Marshalls parking lot that morning, about a block over, where they often leave their cars. It's where they must walk to after work.

I asked my nail tech, Sara, about her daughter and her son in hopes of something lighter. She begins to tell me a story about her son's elementary school. She says that during class, kids could hear the screams of someone being taken right outside of the school building.

The school administration later wrote to those parents that someone not connected to the school was detained outside by federal agents. They reassured parents that students would be safe in class, and that parents would be safe at drop-off and pick-up. But the next day, out of about 30 kids in her son's class, only three showed up. She stops filing my nails. She looks up at me. What do you think I should do? Should I send them to school?

For that moment, I imagined she's my mother, that I am her eight-year-old son, seeing masked, militarized men taking her away. I tell her, if you're scared, don't take them. The following morning, while I'm getting ready for work, I wonder if she's dressing her children for school or if she plans to take my unqualified advice. It's all I can think of for the rest of the day.

The most surprising thing about masked men running around in your neighborhood and terrorizing your people is realizing that the world doesn't stop. You still have to clock in for your job. You still need groceries. You still have to make small talk.

Another text I found in my phone, with a guy from Hinge, October 22. He wants to get coffee in Pilsen this weekend, but we're having trouble finding a time that works. He works at a factory nearby. He texted me that ICE agents are outside his job, and he's covering for coworkers without papers. He keeps having to change the time. I tell him, no worries. He texts, they're just grabbing people and waiting for people to leave work, so now we're telling the night shift to stay home. I hate it here. We never met up that weekend.

Everyone is talking about rules, but there doesn't seem to be any. Our mayor, organizers, and legal advocates have said that ICE and Border Patrol can't do a number of things. They can't go on private property. They can't go on city property. They can't throw tear gas in our neighborhoods, right outside of people's homes. But they continue to do so.

Four days after the start of this operation, they shoot and kill a man in Franklin Park. Not long after, just two miles from where I live, they shoot a woman five times. The Department of Homeland Security keeps talking about people who broke the law, who are here illegally, who committed crimes, but they target all of us, anyone who is Brown, anyone who speaks Spanish or just lives here.

If you get picked up, you could spend a day or a week in detention. So we can't let people outside by themselves anymore. Even those of us with papers, with legal status, are on high alert. They roll up on us in parking lots, on people's front yards, outside of schools, and ask, are you from here? Are you from here?

Other moments from my phone-- on October 4, there's a video from my friend, Bianca. We've all been friends since sixth grade. Bianca's a realtor now. She's in her car, in between showings. She says, guys, this is so sad. Families who I sold houses to last year are calling me now, asking me to put those same houses back in the market. They're heading back to Mexico. A home in the United States was a dream they finally realized. They were just crying of happiness not that long ago, she says. And now they have to let it go.

October 25, an invite to Gabby's annual Halloween party. She called it A Halloween to Remember. After a few hours into the party, I look around and ask where Yazmin is. Gabby looks at me. Yazmin can't come out right now. Oh, shit, I forgot. She's undocumented. I felt so stupid. I felt so careless.

Before the end of the party, Gabby makes sure each guest leaves with a goodie bag, which contains two pieces of chocolate, Skittles, a whistle you can wear around your neck, and a small home-printed booklet instructing you on what to do when you spot ICE. Form a crowd. Stay loud, the cover says.

Code 1, ICE nearby. Blow in a broken rhythm. Pre-pre-pre! This alerts the community that ICE agents are in the area. Code Red, blow in a continuous, steady rhythm when ICE is detaining someone. The last page reads, protect each other, always. Happy Halloween, I guess.

I look back at my call log. There's a list of calls in quick succession one day at 1:26 PM to my mom, and then to her neighbors. I remember exactly what these calls are. I'd seen a post that ICE was two blocks away from my parents' house. I called my mom. I know, she said. There was non-stop honking about 20 minutes ago. That's a thing now-- people honking to alert everyone that ICE is right here. And cars follow behind them until they can't.

Where's Dad? I asked. He's working. My dad calls me later on his way home from work. I tell him our neighbors are safe. Then I say, Dad, you can't go to the swap meet anymore. The owner had said he wanted to keep people safe, but he didn't. More than 20 federal agents took 15 people. That's my dad's spot. It's where he goes for random parts and hardware. But I told him no more Swap-o-rama. He agreed he'd find a different place to do his shopping.

October 20, ICE got to my dad anyway. There's a text from my sister at 10:46 AM. ICE jumped out on Luis. I don't know who he's with. Luis is my sister's husband, and he works landscaping with my dad. I wrote, in all caps, WHERE? RIGHT NOW?

My mom messages me, La migra le llego a tu papa. My dad was shoveling someone's front lawn. When he looked up from his shovel, ICE was right there, the agents just a few feet away. Four cars stood in the middle of the street. One of the agents gripped his coworker's shoulder. Do you all have papers? They all said they did. They think that because no one tried to run, the agents let them continue working. So they did.

Going back through these messages now, I forgot how mad I got at my sister. I was alarmed. My sister seemed to move on quickly when she learned Luis and my dad were fine, which I found annoying. I kept asking her, where are they now? Are they together? Had they called the Rapid Response hotline to report ICE presence in the neighborhood, taken down license plate numbers or makes and models of the cars, information that could help other people at risk in the area?

My sister texts, I am telling you what I know. I am working, and they are working. I don't know how much communication you think I'm getting. My reply-- bro, this is a stop-work matter.

Five weeks into the operation, I saw a cheap flight out of Chicago to New York. I decided to take it, get away for a few days. Part of me felt guilty for leaving. Part of me felt like I should take the chance before it got worse. I spent the weekend with my friends in their living rooms, going on walks to dinner. Nothing about their lives had changed. It was unsettling.

I told them how my body tenses up now when I hear a long car horn, how I look into car windows for masked agents, and that when we get a community alert reporting ICE on our phones, we think of every person we know who lives or works around there, how we text and call immediately, or show up, worried that the other person won't be there. I told them that I wasn't a special case, that this is what everyone I know feels.

Outside of Chicago, it was easier to answer the question, what it's like there? From outside, I could see how much we've adapted, how different everything is now, how extreme things have gotten. It's what I could see going back through my phone that this thing has bled into every single corner of our daily lives, our commutes, our jobs, our families, our dates and parties, and every single conversation.

One last moment I found going through my phone, a text from my relative. She wanted me to know that ICE was at the corner by the pizzeria, where our cousin works. My cousin is the last one in my family who hasn't gotten his papers. I jumped off the train and took one going the other way. I ran down the street. If ICE was here, then I had just missed them.

My cousin had recently told his mom-- my aunt-- that if they ever came in and took him, it'd be all right with him. I'm not running, he'd said. Don't say that, she responded. She was upset that he had brought it up. My mother is upset by this, too. She told me the story over the phone. Let him have his peace, I told her. Perhaps he was just trying to prepare his mother and himself for something he couldn't control. Let him have that.

I stood outside the pizzeria that day, catching my breath. I peered through the glass until I caught a glimpse of him in the back of the kitchen. I waved and pretended I was only walking by. For once, I avoided the conversation completely, for my sake and for his. And I think we both felt relieved.

Ike Sriskandarajah

That story was from Michelle Navarro. She's a writer and a producer on City Cast Chicago, a daily news podcast. It was edited by Chana Joffe-Walt.

Act Two: Who Are the People in Your Neighborhood?

Ike Sriskandarajah

We just have a few minutes left in the show. We'll leave you with one last story. Act Three, Come, Mr. Cab Driver, Won't You Turn That Music Up? Our last story today comes from comedian Mohanad Elshieky, who found himself trapped in an uncomfortable mystery in the backseat of a cab.

Mohanad Elshieky

Most recently, I decided I needed to work more on my small talk. So I was like, you know what? If I do take a Lyft or an Uber next time, I'm going to talk to that driver. I'm going to find a topic, and I'll run with it. And again, I took this man's car, and two minutes in, he starts playing music. And every song he played was something I really liked. So I was like, I got to let him know. So after each song, I would say, dude, this is a great song. Or I'd say, oh, wow, look at that. He's doing it again.

[LAUGHTER]

And I did that for a while, like, 20 minutes of me doing that. And that man did not respond to me once.

[LAUGHTER]

Well, look, I'm a man on a mission. I'll get to him. But then, I swear to God, the music stops, and the thing he starts playing next was my standup comedy on the speakers. And I've never been more terrified in my life.

[LAUGHTER]

Because I was like, I didn't even check if this was my car or not. I left the building, and I was like, this seems completely fine, and I got in. So I had to check in from the back, and I was like, hey, man. Hi. Do you know who this is? And he was like, what? I was like, the guy doing standup on the speakers, do you know who that is? And he was like, no. And I was like, well, it's me.

[LAUGHTER]

And he replied, well, that's good for you. I was like, oh, you're kidnapping me and gaslighting me? This is crazy.

[LAUGHTER]

And then I really thought something bad was about to happen. But then he drove me to the location I gave him, and I did say that out loud. I was like, oh, this is the location I gave you. And he was like, yeah, that's how this usually works.

[LAUGHTER]

And I was like, dude, not to be rude or anything, but are you fucking with me? What is this? What is going on tonight? And he was like, what? And I was like, are there cameras around? Is this going to be on YouTube or something? What is going on? And he was like, sir, I just want you to leave my car.

And I was like, oh, I'm the crazy person here. Oh, I see how it is. OK, I'm the weirdo. Just so you know, whatever this is, you got me. This will haunt me for the rest of my life. I will never forget you. Is that what you want? And then I started leaving the car. I took my backpack, and then I pulled my phone out of the charger.

[LAUGHTER]

Which, as some of you know, doubles as an AUX cord sometimes. So it's been my phone connected to the speakers this whole time. And now there's a guy in New York City who thinks I'm an absolute psychopath.

[LAUGHTER]

Because what happened was, I got into this man's car, this stranger's car, and I played my own music for 20 minutes. And then after each song that I played, I said, what a great song, man.

[LAUGHTER]

Oh, look at that. He's doing it again.

[LAUGHTER]

And then I played my own standup. And then I said, hey, man, excuse me, do you recognize the voice? Yeah, it's your boy right here. It is me. You're getting a good deal here. I'll tell you that. People usually pay to hear this voice. You're getting this for free. Are there cameras around?

[LAUGHTER]

Is this going to be on YouTube, where it belongs? I surely hope so. I have not talked to people since. I think this is it for me. You guys have been an amazing crowd. Thank you so much. Have a great night.

[APPLAUSE, CHEERING]

Ike Sriskandarajah

Mohanad Elshieky is currently on tour. To see where he's performing next, check out his website, mohanadelshieky.com.

["I GOTTA KNOW" BY THE TONETTES]

Act Three: Come Mr. Cab Driver, Won’t You Turn That Music Up?

Ike Sriskandarajah

Well, this episode was produced by me. The other people who helped put together today's show include Phia Bennin, Michael Comite, Emmanuel Dzotsi, Suzanne Gaber, Sophie Gill, Tobin Low, Miki Meek, Katherine Rae Mondo, Stowe Nelson, Nadia Reiman, Marisa Robertson-Textor, Anthony Roman, Ryan Rumery, Frances Swanson, Christopher Swetala, Lilly Sullivan, Julie Whitaker, and Diane Wu.

Our managing editor is Sarah Abdurrahman. Our senior editor, David Kestenbaum. And our executive editor is Emanuele Berry. Special thanks to Mark Fleming, Maria Román-Garcia, Belle Woods, Jen Tonks, Maria Stein-Marrison, Erin Mahollitz, and the second graders at Manitou School.

Our website, thisamericanlife.org. Please consider supporting the show as a This American Life Partner. You'll get bonus episodes-- I did one-- ad-free listening, and more. To join, go to thisamericanlife.org/lifepartners. That link is also in the show notes.

Our episode, The Hand That Rocks the Gavel, was just selected by Apple as one of the Best Podcast Episodes of 2025. That episode is all about immigration judges who almost never speak to the press. If you missed it, check it out. It was released September 21.

This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange.

Ira is out this week. But ever since I told him about the mystery box, he's been leaving me voice messages.

Students

(CHANTING) What is it? What is it? What is it?

Ike Sriskandarajah

And to reward you all for enduring the mystery, we have a special guest to announce the contents of the box. Mr. Torey Malatia, will you tell the people what's in the box?

Torey Malatia

What's in the box? Your mama. Nah. It's a bottle of Advil.

Ike Sriskandarajah

I'm Ike Sriskandarajah. Ira Glass will be back next week with more stories of This American Life.

["I GOTTA KNOW" BY THE TONETTES]